News from home and abroad: The short life of the Andover Advertiser, part 2

“The town of Andover — with its history, its institutions, its extent, its population, its prosperity, its wealth, its business — deserves and needs a newspaper of its own”

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

Today we welcome back new History Buzz writer David Joyner, with part two of his series. The first installment described the beginning of the Andover Advertiser, which launched Feb. 19, 1853, and was initially published by John D. Flagg from a Main Street office opposite Phillips Academy. You can read part one by clicking here.

The Andover Advertiser

‘Agriculture, Trade and Commerce’

Even as dispatches from Civil War battles and other major events unfolded across its pages, the Advertiser’s columns, for the most part, were devoted to issues far more local.

Some of its best material was delivered in morsels no longer than a paragraph or two, about the kinds of things neighbors might share or that get gossiped about after a church service.

As the Advertiser on Sept. 7, 1861 culled out-of-town sources for reports about the newly started war, for example, including the capture of Confederate forts on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, it mentioned the last known location of the 14th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, including “our Andover Company,” then guarding a bridge at Fort Jackson, Virginia, near Washington, D.C.1

The same issue noted an entrance exam for the Punchard Free School held earlier in the week; 47 had been tested, of whom 39 were admitted.

Several months later, at the beginning of March 1862, the Advertiser’s first page was occupied per usual by “entertainments” — in this edition, a poem about reconciling with the will of God, a long frontier story and a musing copied from the Newburyport Herald about clams.

News columns detailed a Town Hall commemoration of George Washington’s birthday. The event had included the recitation of the first president’s farewell speech by seminary Prof. William Greenough Thayer Shedd, “in a most impressive and eloquent manner, holding the earnest attention of the audience, who were at times unable to restrain their applause.”2

Sharing space with the news were advertisements. In its nameplate atop the front page, the Advertiser declared:

“A good advertising medium is the life of agriculture, trade and commerce.”

Every edition sought to promote that life, communicating the promises of vendors near and far who spent 75 cents per “square” of advertising, and 50 cents for subsequent appearances, paid “invariably in advance.”

Dr. W.H. Tibbets advertised pearl enamel filling “for restoring decayed teeth to their former size and beauty.” C.H. Stickney & Co. on Essex Street in Lawrence advertised “dry and fancy goods” from Boston and New York — including all types of cottons, flannels and wool.

Dr. McLean’s Vermifuge could “effect a cure” of the worm, a condition for which the many listed symptoms included headaches, swollen lips and “appetite variable, sometimes voracious with a gnawing sensation of the stomach, at others entirely gone.”

Ayer’s Sarsaparilla was “for purifying the blood” and the “speedy cure” of maladies from tumors to eruptions to pimples.

Then there was Mrs. Wilson’s Hair Regenerator. “Who wants a Good Head of Hair?” announced D. Howarth’s advertisement. Testimonials included that of Rev. Jacob Stevens of Newburyport, who reported that his wife had pronounced the Regenerator “far superior to anything she ever used for the hair.”

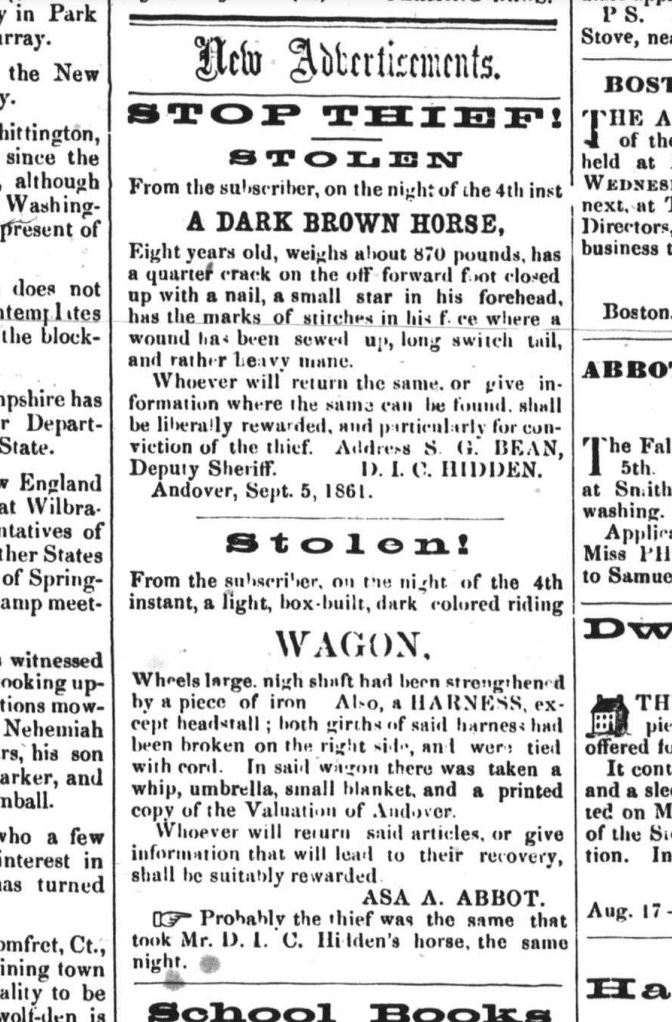

An intriguing advertisement in the Sept. 7, 1861, edition was headlined: “Stop Thief!” It promised a liberal reward for finding an 8-year-old dark brown horse stolen earlier in the week.3

Immediately beneath that ad was a different plea for the return of a harness and wagon, inside which were a whip, umbrella, blanket and printed copy of the town’s valuation. Asa A. Abbot surmised the horse’s thief was probably the same person who took his wagon.

Also curious that day was an advertisement that didn’t actually appear. It might’ve been placed beneath a listing for Bellingham’s “Celebrated Stimulating Onguent for the Whiskers and Hair” but was obscured by a statement, apparently from the publisher, that the advertisement had been discontinued for nonpayment. That came with this declaration: “Let other papers take notice.”

Warren F. Draper, publisher of the paper since taking over Flagg’s portion of the printing business in May 1855, was not above public shaming of delinquent accounts.

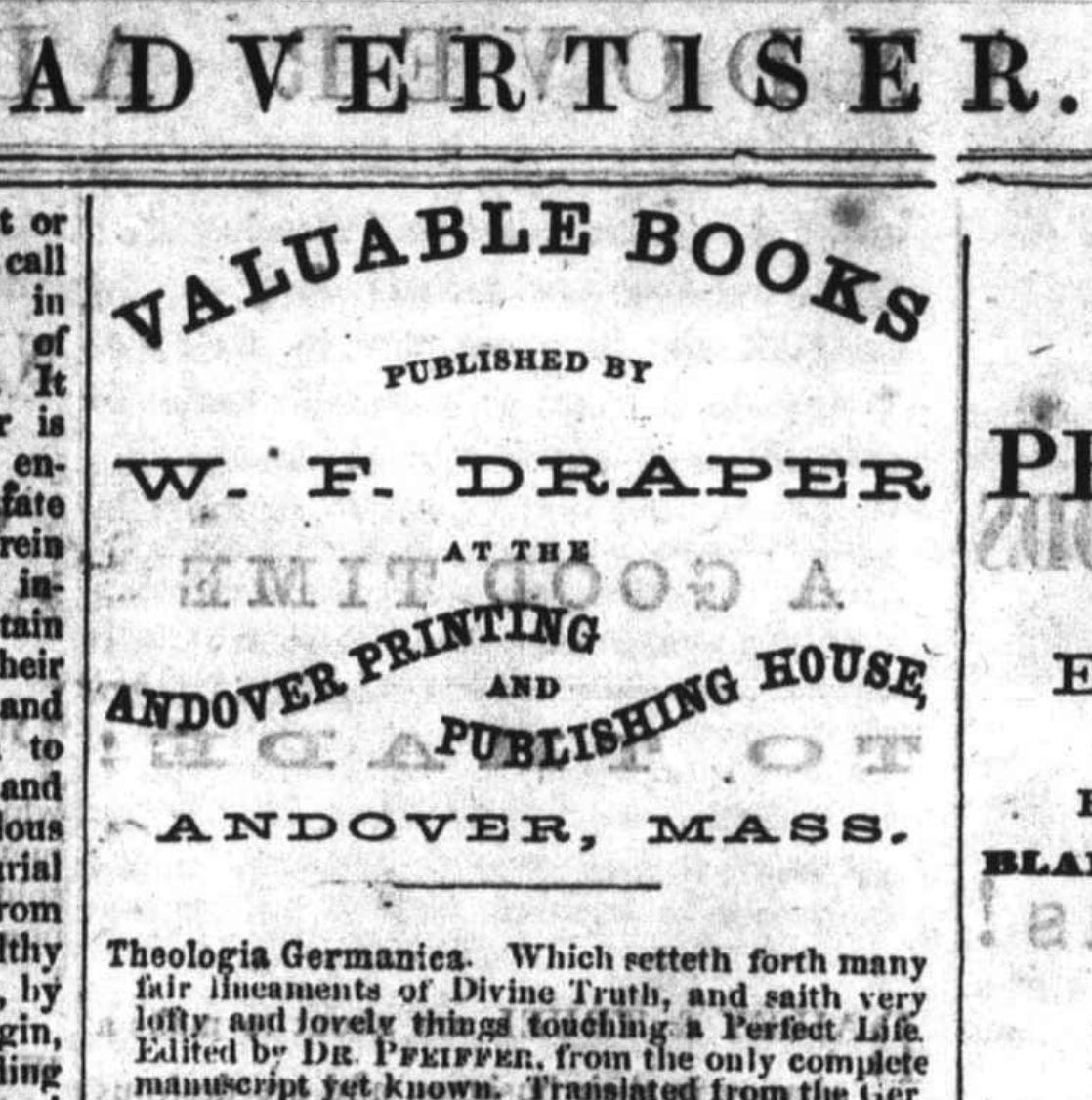

The publisher himself used his Advertiser to announce “Valuable Books” published by his Andover Printing and Publishing House, such as copies of the “Theologia Germanica” treatise discovered by Martin Luther in the 16th century. This edition featured a forward by Calvin Stowe, Harriet’s husband and a professor at the seminary.

Draper wasn’t just dealing in books and Andover newspapers. He sold out-of-town periodicals — including $3 subscriptions to the Atlantic Monthly and Madame Demorest’s Magazine. Scientific American and Harper’s Weekly were also available “at low prices.”4

‘A good readable sheet’

Then as now, the business of newspapering was no guaranteed success. The Advertiser’s March 1, 1862 edition, for example, noted the demise of seven New Hampshire newspapers within a year’s time “for want of support.”

By January 1866, Draper had taken steps to make the Advertiser more profitable. It was selling for four cents per copy, or $1.50 for a year’s subscription. Advertising rates were now $1.25 per square, though Draper had long since started selling “special notices” – at the rate of $1.50 per square — in the front page “reading columns.”

Still, by that point, advertising was clearly being stretched to fill inside columns — which couldn’t have been a positive sign from Draper’s perspective.

As if to plead the case, on Jan. 20, 1866, a short editorial copied from the New York Tribune argued for newspapers as enhancements to the community:

“A good looking thriving sheet helps to sell property, gives character to the locality, and in all respects is a desirable public convenience. … If you want a good readable sheet it must be supported.”5

Shortly thereafter, on Feb. 3, Draper published a “For Sale” notice offering the subscription list and goodwill of his newspaper, “together with the materials used on the same.”

“This affords and excellent opportunity for a practical man to commence business on a small capital,” the notice reported, describing a “good circulation through this and the neighboring towns and as much advertising as is wanted.”6

In a column a week later, Draper noted a “change in business necessitates the relinquishment of further active connection with this paper.” Though it was not clear that the Advertiser had been sold, Draper promised that local news from Andover would appear within the pages of the Lawrence American, published and edited by George S. Merrill.

“Special efforts will be made to give from week to week a full summary of Andover local news, and otherwise, as far as possible, to fill the place of a distinctly local paper,” Draper promised.7

“Since it has been in our charge it has been our study to further the cause of temperance, truth, patriotism and good order in the community, to sustain the fair name and honor of our good town, and, so far as we could, to aid the laudable enterprises of its citizens,” he wrote.

The edition published Saturday, Feb. 10, 1866, closed the 13th volume of the paper — after 13 full years — and put to bed the Andover Advertiser as a standalone, independent newspaper.

Thanks for reading! Please leave a comment, or ask a question, we love to hear from you.

~David

“The Hatteras Inlet Fight,” Andover Advertiser, Sept. 7, 1861. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1861-09.pdf

(Untitled), Andover Advertiser, March 1, 1862. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1862-03_0.pdf

“Stop Thief!” (advertisement), Andover Advertiser, Sept. 7, 1861. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1861-09.pdf

“Periodicals” (advertisement), Andover Advertiser, Jan. 6, 1866. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1866-01.pdf

“A word for newspapers,” Andover Advertiser, Jan. 20, 1866 (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1866-01.pdf

“Printing office for sale” (advertisement), Andover Advertiser, Feb. 3, 1866. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1866-02.pdf

(Untitled), Andover Advertiser, Feb. 10, 1866. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1866-02.pdf

I thought about these posts recently.The local newspaper in Andover, England was named the Advertiser in 1940. Confused me for a minute or two.

Ahhh, the openness and trust to say where you were traveling to and from. Advertising was not controlled to truthfulness. Newspapers copied each other, so one might read about Andover in NY or PA. Hyperbole was freely given. Having search for individuals, these papers gives an insight to their lives, personality, and involvement in the church and community.