News from home and abroad: The short life of the Andover Advertiser, part 1

“The town of Andover — with its history, its institutions, its extent, its population, its prosperity, its wealth, its business — deserves and needs a newspaper of its own”

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

Today we’re delighted to introduce new History Buzz writer, David Joyner.

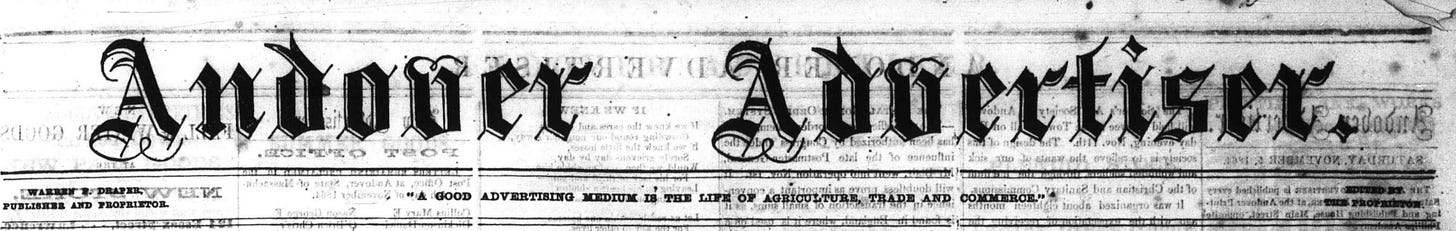

The Andover Advertiser

Andover is unique for many reasons — from its nearly 1,100 acres of AVIS reservations to Clown Town to the fact that it has a newspaper all its own, dedicated to covering the people, business, government and life of the community. Most places in our region north of Boston still get news from locally published sources, but the community weekly is an increasingly rare breed.

“The town of Andover — with its history, its institutions, its extent, its population, its prosperity, its wealth, its business — deserves and needs a newspaper of its own,” the editor of The Andover Townsman declared in a maiden editorial on Oct. 14, 1887.1 The Townsman has fulfilled that purpose for 135 years — and counting.

But The Townsman was not the first such printed source of local news. As Gail Ralston noted in an installment of Andover Stories a few years back, it was at least the third — preceded by the Temperance Society’s Journal of Humanity and Herald, published from 1829 to 1833, and then by the Andover Advertiser.2

The latter was launched on Feb. 19, 1853 to inform and entertain, and for the purpose that its name suggests. And while its trajectory was not especially long — after 13 years, the Advertiser was “united” with, or more accurately, subsumed by, the Lawrence American — its record was notable for its timing. The Andover Advertiser brought news to town — and held a mirror to the community, as any good local newspaper does — during the most violent period of U.S. history. Of 620,000 soldiers killed during the four-year Civil War, from 1861-1865, 53 were from Andover.34

Fortunately, thanks to Memorial Hall Library’s Historical Newspaper Collection, the Advertiser’s record of the war and myriad other events – as seen from Andover, anyway – is readily available to anyone with an internet connection.

Publisher John D. Flagg printed the Advertiser on Saturdays from an office on Main Street, opposite Phillips Academy, and initially sold the newspaper for $1 per year, payable in advance. Subscriptions could be arranged with druggist John J. Brown or in post offices in Andover, Ballardvale or North Andover, among other outlets. A reader could also pick up a single copy for two cents.

The paper was Flagg’s for a couple of years. As of May 12, 1855, he was no longer listed as publisher. Two weeks after that, Warren F. Draper, who had purchased the printing business in which Flagg was a partner, was listed as the new publisher.56

Unlike many 19th century journals, the Advertiser’s objective was apolitical. An editorial published at the outset promised a periodical “intended for people at large” in which “care will be taken that no political party-questions shall be inserted, and none but such as will be of equal interest to all parties.”7

It was not to be an anti-slavery journal — though Andover had its share of abolitionists, including author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Launching not two years before a Know-Nothing sweep of the Massachusetts State House, in 1854, it was not to be a nativist mouthpiece for the emerging American Party, either.

The Advertiser’s first edition pledged: “In regards to Editorials, we do not promise to out-rival our city contemporaries; but efforts will be made to give the readers of the Advertiser such articles as will tend to promote an interest in home productions. A page or more of the paper will be devoted to such reading matter as will be both entertaining and instructive; and it is expected that communications, of local and general interest, will be frequently found it its columns.”8

Sorting Fact from Rumor

Still, the Advertiser served the town in interesting times, as the saying goes, and recorded details of some of the century’s most historic events.

It described, for instance, an outpouring in town on Wednesday, Nov. 7, 1860, in response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as president. Andover had supported the former Illinois congressman with 489 votes — to 87 for Illinois Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, 55 for Tennessean John Bell and 14 for the Southern Democrat John C. Breckenridge. The headline announced: “The Election of Lincoln and (Vice President Hannibal) Hamlin Celebrated in Andover; Great enthusiasm manifested.” The Advertiser described “such a crowd as is seldom seen in Andover.”9

“The scene was enlivened by an almost constant discharge of rockets, Roman candles and the firing of guns,” the paper reported, while describing every turn of a celebratory parade led by a local band of Republican-supporting “Wide-Awakes.”10

At the Theological Seminary, lamps were hung in each windowpane, creating what the newspaper described as a “magnificent appearance.” At Phillips Hall, lamps in windows on the second and third floors were arranged to spell “Veritas Vincit” — truth conquers. (The Stowe household, incidentally, was “lighted behind colored curtains, which produced a unique and beautiful effect.”)

Reporting on events over the next several years came with some difficulty, as was apparent April 13, 1861, with an editor’s lament on the challenges of sorting fact from rumor: “The dispatches which are received from Washington and the South from day to day are so various and conflicting that it is impossible for one to arrive at any satisfactory conclusion regarding the public state of affairs.”11

Troops were gathering. There was talk of an imminent attack on the nation’s capital. Indeed, as Andover readers were digesting that news, some 830 miles to the south, Fort Sumter was under siege and soon to be abandoned to South Carolina secessionists.

The following week, the Advertiser duly reported: “We have lived through a week such as we have never seen before. For the first time has been heard the tramp of our citizen soldiery preparing for battle — not to repel an invading army, or to redress grievances inflicted by a foreign government upon our frontiers, but to uphold the country against traitors within our own borders and almost at the very heart of the country.”

There was to be a town meeting that evening to discuss the “present crisis” — including the formation of a volunteer company.

Two years later, the Advertiser reported on the battle of Gettysburg and the fall of Vicksburg — once again, days after the fact: “By the blessing of God, victory is ours at last — such victory as had no place even in the anticipation of the most hopeful a week ago — such victory as has not before rewarded the earnestness of the people and the bravery of our soldiers — such victory as thousands had given up all hope of even being achieved by our armies. The confident and defiant army of Gen. Lee has been met and completely defeated at last by our army of the Potomac ….”12

Not two years later, with the war officially ended, the Advertiser reported on Lincoln’s assassination, describing services at South Church memorializing the president. The church was “completely filled,” it reported, including by veterans who “attended in a body, with the band and colors.” Memorials were held elsewhere in town, at the Baptist Church and Free Church. Businesses were closed. Houses were marked with “badges of mourning.”13

At this tragic turning point, the newspaper’s editor ruminated on a plot “which for diabolical malignity has not been surpassed in the annals of the world’s history — a plot to destroy the chief officers of the government by assassination.”

Look for Part 2, where we'll share the rest of the story of the Andover Advertiser.

Thanks for reading. Please like, share, and leave comments. We love to hear from History Buzz readers!

~David

(Untitled), The Andover Townsman. Oct 14, 1887. Memorial Hall Library Digital Archive. https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/ATM-1887-10.pdf

Gail Ralston, “Andover Stories: Chronicling the town’s news for 127 years,” The Andover Townsman, Oct. 30, 2014. https://www.andovertownsman.com/news/local_news/andover-stories-chronicling-the-town-s-news-for-127-years/article_d3efdbaa-258a-58b6-9f4c-14b098eaf074.html

Drew Gilpin Faust, “Death and Dying,” National Park Service Civil War Era National Cemeteries.” https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/national_cemeteries/death.html

(Untitled editorial), Andover Advertiser, Feb. 19, 1853. (Memorial Hall Library Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1853-02.pdf

“27 School Street,” Andover Historic Preservation, Andover Historic Preservation Commission. https://preservation.mhl.org/27-school-street

Andover Advertiser, May 26, 1855. https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1853-02.pdf

Ibid, Andover Advertiser, Feb. 19, 1853.

Ibid, Andover Advertiser, Feb. 19, 1853.

Andover Advertiser, Nov. 10, 1860. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1860-11.pdf

“The election of Lincoln and Hamlin celebrated in Andover,” Andover Advertiser, Nov. 10, 1860. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1860-11.pdf

“National Affairs,” Andover Advertiser, April 13, 1861. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1861-04.pdf

“Victory,” Andover Advertiser, July 11, 1863. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1863-07.pdf

(Untitled), Andover Advertiser, April 22, 1865. (MHL Digital Archive) https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1865-04.pdf

This is interesting. I read about a "circular" recently... How news travelled from place to place because newspaper editors/publishers would mail copies to one another. Thank you. David.

David - Thanks for an interesting history read!!