Miscellany Mondays: POPCORN - An American Icon, part 2

From Campfire to Circus Ballyhoo to Microwave

History Center Director of Programs Martha Tubinis is back with part 2 of series on her favorite obsession: popcorn.

NOTE: If you’re reading this as a email, part of it might be cut off. To read the whole post, just click on the title to read it all on History Buzz.

The Circus, Railroad, and Other Cultural Influences on Popcorn, 1870s-1920s

Popcorn played an important evolving role in the daily lives of 19th century Americans. The fun and magical appeal of watching the corn transform, the smell, the popping noise, the taste and even the rudimentary ways of popping all converged to lay the groundwork for the unique popcorn experience. Three other 19th century cultural phenomena were integral in the evolution of corn popping into a quintessential American experience: The circus, the invention of the steam engine and the evolution of the railroad.

The Circus Comes to Town

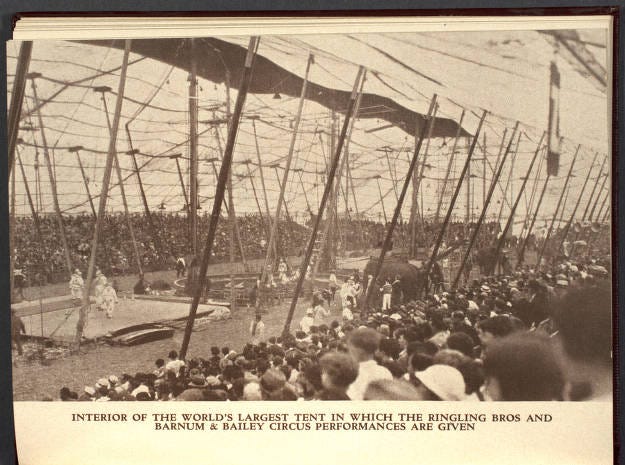

The circus, meaning “circle” in Latin, came to our shores from Europe in the eighteenth century.1 Very quickly it became a popular entertainment venue and adopted an American character. Soon, the circus became known for its large caravan of wagons, which became more ornately decorated as the circus grew in scope and size. The circus coming to town became one of the biggest social events of the year.2

As the century marched on, the circus grew in depth, breadth, and popularity. With the invention of the steamboat in 1807, circuses could travel further inland, away from the east coast. Now, the circus could be transported more quickly and efficiently through all of America’s rivers and waterways south and to the Midwest.3

Steam locomotion also gave way to the creation of the railroad in nineteenth century America. As noted circus author Janet M. Davis says,

. . . industrial steam and locomotive power remade the circus, making it gigantic, itinerant, intricately organized, and able to travel coast to coast.

The construction of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 facilitated the ease of transporting the circus trains.4

Prior to the arrival of the circus in a region teams of travelling workers went town to town hanging circus posters which advertised the circus date and created local anticipation and excitement.5 The actual arrival of the circus train into a town with steam wafting and brakes meeting metal signified the beginning of what had evolved into an unforgettable multisensory experience. Unique to America, circus day meant no work and no school for miles around. It wasn’t unusual for ten to twenty thousand people to rise before dawn to go into town to participate in the grand circus parade.6 The parade could be a mile long and extended from the train to the circus site.7

The circus parade was free, and for many the only way to see the grandeur of the circus without having to pay. Rolling circus wagons contained loud menacing animals, displayed the “freaks,” and transported the hundreds of circus performers – clowns, aerialists, magicians, strongmen, fortune tellers and animal trainers brandishing torches and setting off fireworks.8

Included in the parade and integral to its appeal were the music wagons. There were bands and a wagon carrying the unusual sounding steam organ called the calliope.9 Also unique to the American circus were the popular historic reenactments called spectacles which grew in size and importance as the century progressed. These spectacles and indeed the entire multisensory circus experience became the preeminent manifestation of patriotism in America and remained so through the 1920s.10

And, we can’t forget that American popcorn was an integral component of the multisensory experience forever bonding “popcorn” and “circus.”

1893 World’s Columbian Exposition

In the 19th century, the only real cultural competitor to the circus was the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago recognizing the 400th anniversary of Columbus arriving the New World. It represented a parting of the ways with old rural agricultural America and the dawn of a new era of internationalism, industrial and technological achievement and urbanization.11

The Exposition was an unparalleled venue for the display of American ingenuity. Twenty-two million visitors over a 6-month period viewed hundreds of exhibits, entertainment halls, and international food and displays.

Three inventions featured there had lasting impacts on the popcorn and popper industry.

First was the spellbinding inception of electric lights and power. “Everything the glowed, that sounded, that moved at the fair was powered by electricity…it foretold the coming supremacy of electricity in American life and industry.”12 At the Midway Plaisance, a 600-foot-wide avenue, electricity powered water fountains, motorized sidewalks and propelled gondolas through the many waterways.

The second event of import was the introduction of the first Ferris Wheel. It was designed using the bicycle wheel as a structural model. The iron wheel had 36 wooden pendulum cars with a forty-person capacity per car.13 The layout of the Midway Plaisance - ornamented buildings, electric lights, separate game and ride area- became the blueprint for amusement park design for the next 60 years.

The third and most important and revolutionary invention - as far as popcorn is concerned - was the C.R. Cretor popcorn wagon.

Charles Cretor was a classic inventor who also had a flair for salesmanship. He was a sign painter and candy store owner. In the window of his Chicago store he placed a hand operated peanut roaster, which functioned poorly but did the job and attracted customers. Ever the tinkerer, he adjusted the machine to become a coffee and popcorn roaster as well. Soon, the popcorn dominated and the peanut roaster became an attachment.

After a few more years of tinkering Cretors created the very first commercial popcorn wagon, called Wagon No. 1.

The Cretor Wagon could also roast 12 pounds of peanuts, 20 pounds of coffee and bake chestnuts. The popcorn wagon incorporated many of the themes discussed thus far. It was powered by Naphtha gasoline, steam, made of metal and looked like a circus wagon in design and spirit. The gas created steam which provided the energy to engage the agitator. It had an obvious crank upon which sat a whimsical Tosty Rosty clown.14

The Wagon No. 1 also had large bicycle wheels that allowed the owner to be a mobile popcorn salesman and move the concession stand on wheels to whatever venue they desired.15

For added attraction (and one can assume a nod to the circus industry) Cretor added noise making features and painted it to look like a circus wagon. It came equipped with a bell rung by the miniature toy clown, two torches and later added,

a small whistle connected with the exhaust, which blows automatically and sounds like the exhaust of an engine and just loud enough to attract attention.16

Cretors’ instruction manual goes on to say that the little clown,

“is a great card, it amuses the children and also those of larger growth.”17 The cover to the pan was made to rise up as the corn pops such that the corn could “escape over the top of the pan like a fall of snow.”18

After the Columbian Exposition

The association between Cretors popcorn wagons and the circus only strengthened after the 1893 expo. It continued strong well into the 1920s. Charles Cretors improved upon his No.1 Wagon and soon added larger horse drawn wagons followed by engine powered trucks. They were still made to look like a circus wagon and now matched them in size.19

Amusement park venues become increasing popular in the 1880s and after the Columbian Expo. “Trolley parks” were built at the end of lines hoping to increase weekend trolley usage. Though more ride-oriented, they shared the same multisensory stimulation and appeal as the circus. And, of course, the mobile commercial popcorn wagon and the new Cretors Earnmore electric popping machine were a perfect fit in the carnival atmosphere of the amusement park.20

From the 1920’s Onward - Poppers and Popcorn Trends

In addition to the comfort and fun of being with your family and friends, the popcorn experience also stimulated all five senses. The commercial popcorn wagons (and their kettle poppers) at circuses, carnivals and amusement parks, drive-ins and movies were a show unto themselves: visually busy and colorful, made a variety of noises to attract attention, utilized hand cranks for stirring, emanated a buttery aroma and finally comforted and rewarded the hungry with mouth pleasing hot buttery popcorn.

As the circus diminished in importance, movie theaters reigned as the premier popcorn eating venue in the 1930s peaking in the 1950s. Drive-in movie theaters were another popular popcorn venue through the 1960s.

Though considered dangerous, electric poppers had become popular appliances to use at home. Eventually, cranks were not needed because the poppers had built in thermostats to control temperature.21

The introduction of the television in the 1950s resulted in diminished movie attendance but ushered in the era of consuming popcorn at home. With the 1960s came a plethora of gourmet cooking shows.22

In the 1970s VCRs were introduced and women entered headlong into the work force, further cementing the eat-at-home trend and a desire for convenient food preparation.23

Orville Redenbacher was busy in the lab creating his hybrid popcorn seed which he introduced in the early 1970s. He positioned his new larger and fluffier popcorn as gourmet and portrayed himself as a folksy Midwesterner.24

Also introduced in the 1970s were the Presto Hot Air Popper and the microwave.25 The hot air popper dried out the popcorn by driving down the ideal moisture content of 13.5%.26

The microwave popping experience virtually obliterated the old-fashioned multisensory circus experience – initially, the popcorn bag itself had to be frozen in order to package the popcorn and the oil together.27

By 1980 the magical popcorn experience had devolved into throwing an opaque bag of frozen corn and oil into a microwave oven, the din and design of which suppressed the smell, the sound of popcorn popping, pleasurable visual references and the tactile satisfaction of stirring the kernels. The popcorn experience that took almost two centuries to evolve into something special had been expunged.

But all is not lost! As a popcorn aficionado, I highly recommend a Whirleypop popper for the full popcorn experience at home.

~Martha

How about you? Do you have associations and fond memories of popcorn? Is it the circus, a movie theater or drive-in, amusement park, or maybe at home watching your favorite TV show?

Thanks for reading! Leave us a comment below if you have memories or thoughts to share. We love hearing from History Buzz readers!

Tait, Peta, and Katie Lavers, eds. The Routledge Circus Studies Reader. First edition. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York: Routledge, 2016. p.350

Renoff, Gregory J. “The Circus Parade.” In The American Circus, edited by Susan Weber, Kenneth L. Ames, and Matthew Wittman, 152–75. New York: Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture, 2012. pp. 159-161

Davis, Janet M. “The Circus Americanized.” In The American Circus, edited by Susan Weber, Kenneth L. Ames, and Matthew Wittman, 22–53. New York: Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture, 2012., p310

Davis, pp 25 and 32

Stirton, Paul. “American Circus Posters.” In The American Circus, edited by Susan Weber, Kenneth L. Ames, and Matthew Wittman, 106–35. New York: Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture, 2012, p.110

Davis, p.48

Renoff, p.162

Renoff, p.162

Botstein, Leon. “Circus Music In America.” In The American Circus, edited by Susan Weber, Kenneth L. Ames, and Matthew Wittman, 176–99. New York: Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture, 2012, p.193

Wittman, Matthew. “The Transnational History of the Early American Circus.” In The American Circus, edited by Susan Weber, Kenneth L. Ames, and Matthew Wittman, 54–85. New York: Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture, 2012, pp.51, 57

Burg, David F. Chicago’s White City of 1893. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1976., p.xiii

Burg, p.20

Burg, p.224

Cretors.com

Smith, Andrew F. Popped Culture: A Social History of Popcorn in America. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, 1999, p.92

Cretors Historic Catalogues p. 11

Cretors Historic Catalogues

Cretors Historic Manuals

Cretors Company History

Cretors Company History

Smith, pp.96, 101,103,120,124

Lifshey, Earl. The Housewares Story: A History of the American Housewares Industry. Chicago: National Housewares Manufacturers Association, 1973, p.368

Senauer, Benjamin, Elaine Asp, and Jean Kinsey. Food Trends and the Changing Consumer. St. Paul, Minn., U.S.A: Eagan Press, 1991, p. 4

Smith pp.139-142

Dailyhistory.org

The Popcorn Board Industry Facts

Smith, p. 136

A fascinating travelogue through time - the popcorn wagon, Columbian Exposition and even Orville Redenbacher. Rich heritage...

Jiffy pop! The expanding aluminum foil appeared to be right out of the Jetsons’ kitchen. In fact, I believe I saw that marketing invention as part of the Henry Ford at Dearborn, Michigan.