History of the Shawsheen River, part 2

In 2022, the Town of Andover commissioned the History Center to write the history chapter of the town's Master Plan for the Shawsheen River. This is part two of the chapter.

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

PART 2: Post 1646 through 1700

Introduction

You can read Part 1, the deep history of the area, by clicking here.

The Indigenous people’s way of living was very different from the English settlers’ ways. For example, instead of being organized into divisions that could be neatly mapped with clear, unmovable boundaries (cities, towns, counties, etc.). The local Indigenous people were organized into bands that were fluid depending on marriage and familial alliances, and strategies of leaders.

Attitudes and understandings about land use and ownership between the Indigenous people and the English settlers were inherently different. For the Native people, land was associated with people as long as they used it. When the users of that land moved on, the land was open for use by others. The English concept of absolute land ownership led to misunderstandings and abuse as Indigenous people’s rights to their land was taken away.

The land loss experienced by Native people exemplifies the power dynamics between Native people and English colonists. Some land was purchased legally, according to English law, but most often vastly undervalued. Some land was acquired through questionable, coercive, fraudulent, or corrupt means.1

The original English settlement of Andover was in what is now called North Andover. English colonists settled together around the meeting house. Homes were to be built nearby and it was intended that families would live close to the meeting house. Wood lots and land for planting were often situated far from the meeting house. Given the distance between home and farm land, colonists often built dwellings close to their land to make their work easier. Their primary homes, however, were still required to be near the meeting house. This arrangement didn’t last for very long. Within 30 years of settlement the south part of town was settled and had a higher population than the original settlement.

Mills and the colonial economy

English settlers came from an environment with scarce natural resources and plentiful labor. The New England environment they settled had the opposite: plentiful natural resources and scarce labor.

The economy the settlers created was dependent upon what has been called the “4 F’s”: furs, fish, farms, and forests. Water and wood were central to the economy.2

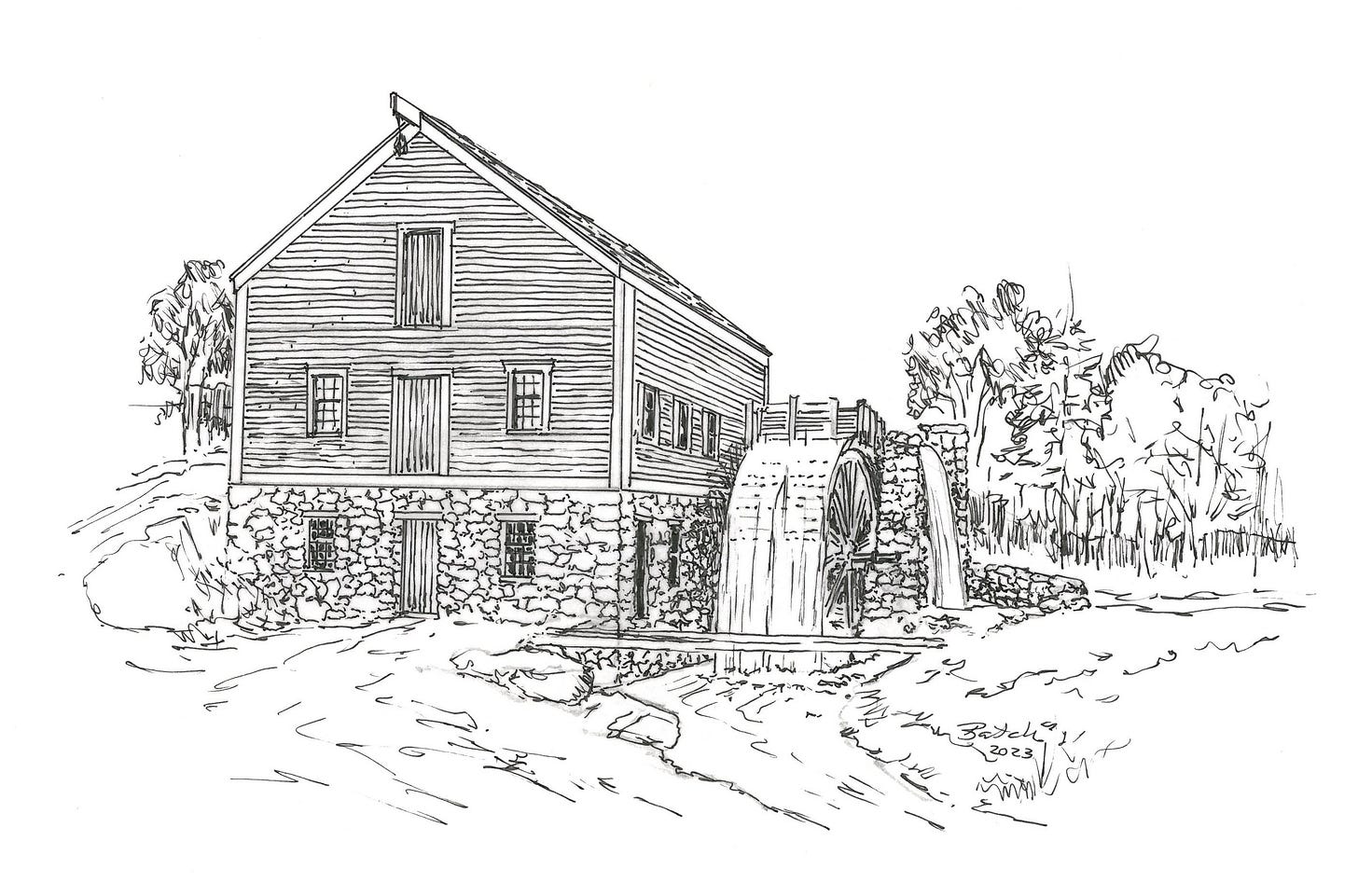

Because of the dependency on wood, a sawmill was often the first commercial building built in a new community. Wood was needed for homes and for building other necessary mills. In addition to saw mills, grist mills for grinding grain were critical to the survival of a community. Iron manufacture was also needed to produce fasteners/nails, plowshares, horseshoes, cookware, firearms, and other edged tools.

Colonial mills were built by millwrights. A successful millwright’s skills could include that of a carpenter, joiner, stonecutter, mason, blacksmith, wheelwright, and surveyor.3

Mills were so important that communities often offered inducements to attract millwrights. Inducements could include free mill site and adjoining land, tax exemptions, monopolies, military exemptions, and cash. Miller’s fees were not small, often ¼ of the lumber or grain produced was charged. However, despite the high fees, noise, water usage, pollution created by mills, millers and millwrights were valued members of the community.4

A good mill site needed to have a water source, which could be a river or a stream. An overshot wheel needed 10’ of head or water height to produce enough energy to move the wheel and power machinery. Dams and waterways were built to create millponds that served as a reservoir during dry times of the year and gave the miller control over water flow.5 The weight of the falling water and the velocity of the water when it hit the wheel’s paddles or buckets determined the amount of power the wheel could produce. A good overshot wheel used 50-70% of the water’s energy. The mill site also included a mill trace to carry water to the wheel, a sluice with a gate called a penstock to direct water onto the wheel, and a traceway to carry water away.

The post-contact history of Andover and New England is tied to two terms related to mills: “mill privileges" and "flowage rights”

“Flowage rights” for a dam set a pre-determined level of water behind the dam to ensure a steady flow of water to serve mills located downstream.

A “mill privilege” conferred the right of a mill-site owner to construct a mill and use the power from the stream to operate the mill with due regard to the rights of other owners along the stream’s path.

There are a few concepts wrapped up in those two definitions.

Early New England settlements and towns were based on the practices and legal structures settlers brought with them from England, including the use of common land. For example, towns like Andover were built around a central Common where residents could let their animals graze.

The same approach applied to common use of rivers and streams. Long before the English settlers arrived, the Indigenous people relied on waterways for transportation and drinking water, and were an important source of food.

English settlers continued to use waterways in these same ways. Settlers followed the English Common Law concept that “water flows and ought to flow, as it has customarily flowed.” In New England, however, English settlers’ need for building materials and grain often conflicted with this practice of the common waterway.

Because mills were expensive to build and required special skill to maintain, a miller’s monopoly on the service was governed by the social contract that in return for the miller’s investment and mill privilege residents would be charged reasonable rates for the use of the mill.

The associated flowage rights assured that the miller could build a dam or change the flow of the stream to meet the needs of the mill. In return, he was responsible and legally liable for the effects of his actions on people upstream and downstream from him. If the miller’s dam caused a farmer’s fields to flood, for example, the miller was responsible for reimbursing the farmer for his loss. By those same rights, residents upstream and downstream from the mill could legally break the miller’s dam and return the stream to its natural course until the issue was settled in court. Everyone had equal rights to the waterway.6

17th century mills in Andover

In Andover, as in other New England towns, mill privileges and flowage rights were granted by the town's governing body and were included in property deeds, as we see here with the Shawsheen River and Hussey’s Pond.

As early as 1682, Andover Town Proprietors granted a “mill privilege on the Shawshin near Roger’s Brook to any inhabitant willing to build a sawmill.” Joseph Ballard erected a grist mill along the Shawsheen River in what is now Ballardvale.7 Joseph and John Ballard later were the first to establish a fulling mill in Andover.

Fulling is a critical step in woolen production. A newly-woven piece of cloth is loose and airy. Fulling is the process of consolidating the fibers to form a denser fabric. Woven fabric is first cleaned of grease and oils using an acidic liquid, such as stale urine. The cleaned fabric is beaten to compact the threads. Fulling mills used enormous water-powered hammers or beaters. The rhythmic thump of the beaters would have been a familiar sound for those who lived near the mill.8

Other mills were established along the river in the 17th century.9 Further back on Roger’s Brook leading to the river, in 1675 a tannery was in operation using water power from the brook and draining into the Shawsheen River.10\Moving north, in 1678, Thomas Chandler[1] ran his iron works along the river off Stevens Street on the west side of the river. Chandler was a blacksmith by trade and served as a Representative to the Massachusetts General Court.

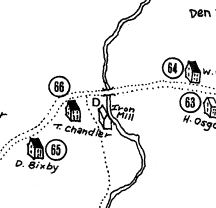

Moving north, in 1678, Thomas Chandler11 ran his iron works along the river off Stevens Street on the west side of the river. Chandler was a blacksmith by trade and served as a Representative to the Massachusetts General Court.

Among other locations around town, mill privileges in Andover were granted at what would become the town’s four mill districts along the Shawsheen River: Ballardvale, Abbot Village, Marland Village, and Frye Village.

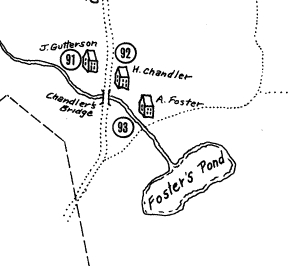

17th century bridges

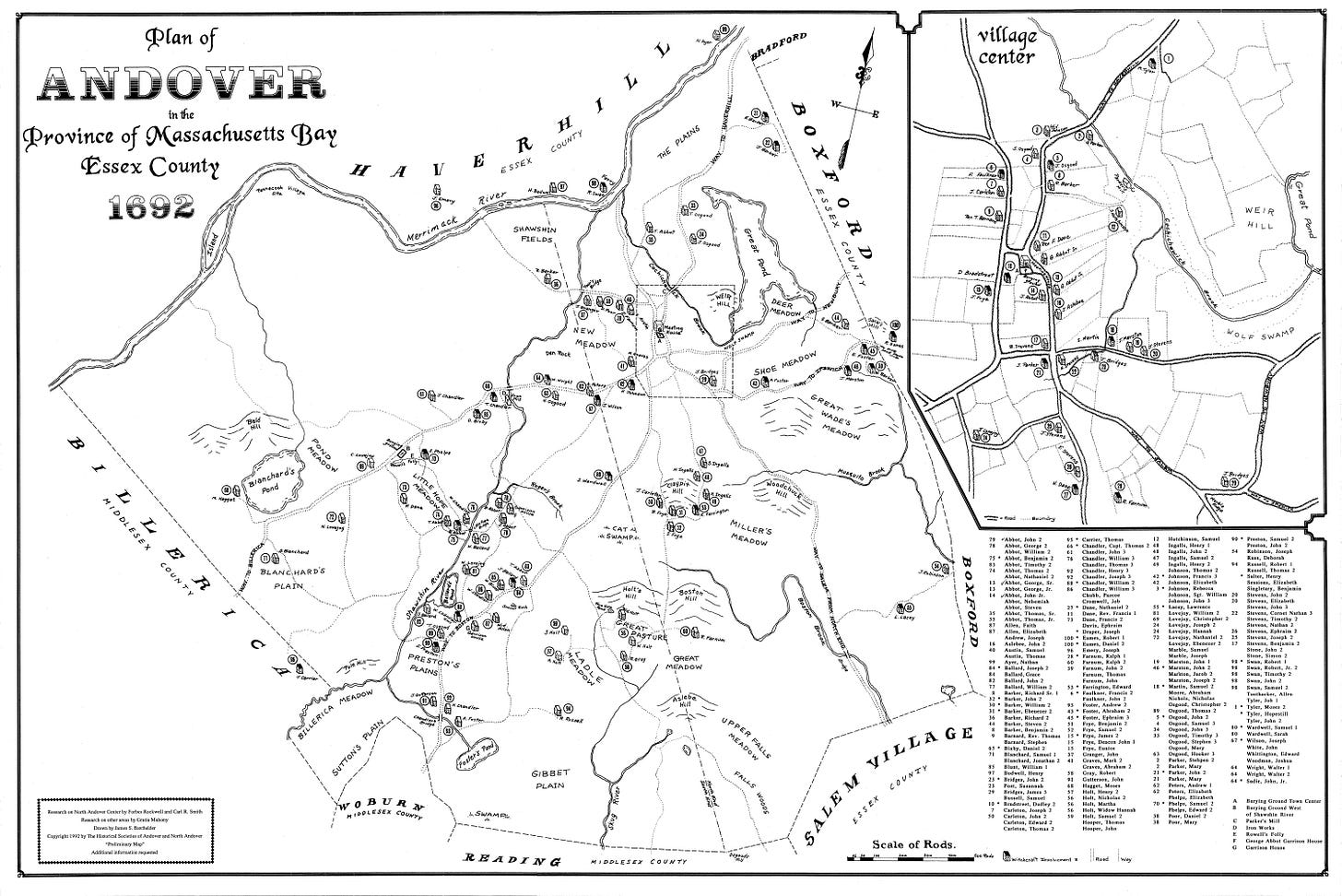

The 1692 map of Andover shows homes, mills, and farms all along the Shawsheen River, along with the bridges that crossed the river. On Stevens Street, a bridge was constructed next to Thomas Chandler’s iron mill.[1] Further south, the “Little Hope Bridge” crossed the river at the intersection of Lupine and Central Streets, and in Ballardvale on River Street was Chandler’s Bridge, named for William Chandler. The brook running from Foster’s Pond ran under Chandler’s Bridge.

Other 17th century uses of the river

Fishing was another use of the river during the second half of the 17th century. In 1681, a 21-year monopoly on fishing places from the mouth of the Merrimack River 20 rods (330 feet) downstream on the Shawsheen River was granted to Captain Bradstreet, Lieutenant Osgood, and Ensign Chandler.12 The 20 rods didn’t extend very far up the Shawsheen River, but the mouth of the river was certainly the most lucrative location. The English settlers harvested the same fish from the river that the Indigenous people did: alewives,13 herring, salmon, and shad.

In 1692, during the Salem witch hysteria, Samuel Wardwell claimed that he was induced to make his signature in the Devil’s book and was baptized in the Shawsheen River.

This second installment of the Shawsheen River history is a very brief introduction to area just after English settlement in 1646. You can read Part 1, the deep history of the area, by clicking here. In our next installment, we’ll look at the history of the river in the 1700s.

Thanks so much for reading! Please leave a comment, like, and subscribe. You can help make History Buzz more visible to other history-loving readers.

~Elaine

Resources 1646-1700

Andover Historic Preservation website, https://preservation.mhl.org/

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Riverside Press Cambridge, 1880

Colonial America’s Pre-Industrial Age of Wood and Water, https://www.engr.psu.edu/mtah/articles/colonial_wood_water.htm

Fuess, Claude, The Story of Essex County, Volume 1, Chapter 2, “Essex County in Indian Times,” American Historical Society, 1935

https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/americanenvironmentalhistory/chapter/chapter-5-commons-mills-corporations/

Lord, Philip, Mills on the Tsatsawassa: Techniques for Documenting Early 19th Century Water-Power Industry in Rural New York, Purple Mountain Press, Fleischmanns, New York, 1983.

Richardson, Eleanor Motley, Andover: A Century of Change 1896-1996, for the Andover Historical Society, 1995

Strobel, Christoph, Native Americans of New England, Praeger, 2020, p 80

Colonial America’s Pre-Industrial Age of Wood and Water

IBID

IBID

https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/americanenvironmentalhistory/chapter/chapter-5-commons-mills-corporations

https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/americanenvironmentalhistory/chapter/chapter-5-commons-mills-corporations/

Historic Preservation website, 210 Andover Street

http://www.witheridge-historical-archive.com/fulling.htm

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Riverside Press Cambridge, 1880, p102

1692 map of Andover

Thomas Chandler is also known for his role in the Salem witch trials of 1692.

Bailey, p152

Alewife illustration, https://www.thecricket.com/news/the-alewives-cometh/article_02dbec58-9780-11eb-b375-7f236b29d932.html

The passage about mills and the rights and obligations of millers is interesting.