History of the Shawsheen River, part 1

In 2022, the Town of Andover commissioned the History Center to write the history chapter of the town's Master Plan for the Shawsheen River. This is part one of the chapter.

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

In presenting this deep history of the Shawsheen River, we are grateful to the research and writings of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki. You can learn more on their website, https://www.cowasuck.org/. In September 2022, leaders of the Cowasuck band, Denise and Paul Pouliot, spoke at a Town of Andover forum. You can watch the forum by clicking here. The Pouliot’s presentation begins at the 33-minute mark.

PART 1: Deep history of the area, pre-1646

Introduction

Note: Historian Christoph Strobel uses the term “deep history” to describe the time prior to 1490 and European contact rather than using “pre-history.”1

Archaeologists identify the Indigenous people of the Late Pleistocene era (10,000 and earlier) as “Paleo Indians” who had “sustainable, complex, sophisticated lifeways” that included forest management and agriculture.2

Archaeological evidence for the Archaic period (8,000-1,000 BCE) that followed indicates the Indigenous people regularly revisited sites during specific times and seasons. Evidence that exists around ponds and lakes indicates seasonal use. By 1400, Indigenous people farmed, foraged, and hunted throughout New England.3

The Woodland period (1,000-1500 BCE) ended in 1490 with the arrival of Europeans and diseases that caused devasting epidemics that killed between 50% and 90% of the Native population. During the Late Woodland period (900-1650 CE) inland Indigenous communities were predominantly agricultural along with foraging, hunting, and fishing. They lived a semi-sedentary life, moving seasonally and when farm fields were exhausted.4

There was an abundance of communities that existed throughout the long pre-colonial history, and that could be found all over the river valleys in many places. In fact, the location of many Indigenous settlements were right in the same places and many New England towns and the now post-industrial cities such as Manchester (New Hampshire) and Lowell (Massachusetts).5

A village/trading post along the Merrimack River - that is now referred to as "the Shattuck farm site" - is a good local example. Indigenous residences along other rivers and tributaries, including the Shawsheen River, were likely similar to this site.6

The Shattuck farm site

The Shattuck site, as it is called, was in use for at least 8,000 years. The site was sometimes a base camp, but usually a seasonal camp for fishing, hunting, nut gathering in the Fall. Or it was used as a specialty camp such as projectile making site. It was unlikely that it was occupied in the Winter due to exposure to strong winds from the north.

Massachusetts state archaeologists conducted a survey of the area in 1981. Artifacts and fire pits were dated using radiocarbon technology.

The area was farmed by colonists starting in 17th century, so valuable archaeological date was disturbed by ploughing early on and amateur archaeology collecting in the 19th and 20th centuries. To address the losses, state archaeologists searched out major collections that had been acquired by amateur collectors and were able to piece together a lot of information to add to what they found in the 1981 survey.

There’s a lot more information about the site available. We’re planning to post more about the Shattuck farm site and the deep history of that area in the future.

Shawsheen River

Scant archaeological evidence remains of Indigenous people’s lives from the Late Pleistocene era through the Late Woodlands era (and European contact) along the Shawsheen River as it flows through Andover.

There is a high degree of probability that Indigenous people settled in areas along the Shawsheen River that provided them with needed resources: access to water for sustenance, fishing, and travel, land for agriculture and residences, and woodlands for gathering and hunting. These are the same areas that would later be settled by English colonists.

Through court documents, we have a narrow glimpse into where Indigenous people might have settled. The 1646 attestation of the sale of Andover described “the Indian called Roger & his company” who “may have liberty to take alewives from the Cochichawick River (Shawsheen River), for their own eating” also “the said Roger is still to enjoy four acres of ground where he now plants.”

Attestation:

At a General Court, at Boston 6th of the 3rd m, 1646

Cutshamache, sagamore of the Massachusets, came into the Court, and acknowledged that for the sum of 6 pounds & a coat, which he had already received, he had sold to Mr. John Woodbridge, in behalf of the inhabitants of Cochichawick, now called Andover, all his right, interest, and privilege in the land six miles southward from the town, two miles eastward to Rowley bounds, be the same more or less, northward to Merrimack River, provided that the Indian called Roger & his company may have liberty to take alewifes in Cochichawick River, for their own eating; but if they either spoil or steal any corn or other fruit, to any considerable value, of the inhabitants there, this liberty of taking fish shall forever cease; and the said Roger is still to enjoy four acres of ground where now he plants. This purchase the Court allows of, and have granted the said land to belong to the said plantation forever, to be ordered and disposed of by them, reserving liberty to the Court to lay two miles square of their southerly bounds to any town or village that hereafter may be erected thereabouts, if so they see cause.

It’s likely that “Roger & his company,” who lived in what they called Cochichawicke, were an Abenaki band organized as part of the Pennacook Confederacy under the leadership of the Pennacook-Abenaki sachem, Passaconaway.

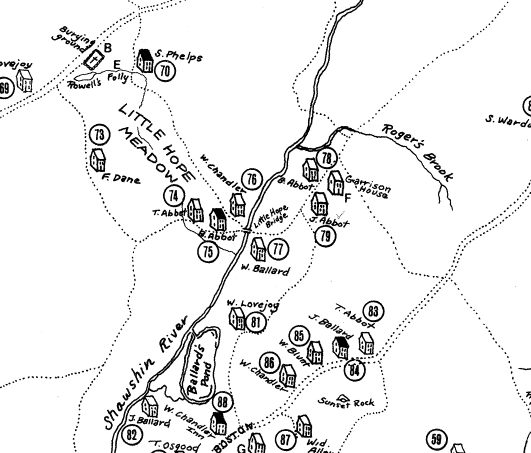

Lacking archaeological evidence of this settlement, we can surmise that Roger and a small group of people, perhaps his family, lived on four acres along the river near the mouth of what later became known as “Rogers Brook.”

The homes the group occupied would have been a type of dwelling that is variously referred to as lodges, wigwams, wetus, and long houses. These dwellings were round, oval, or conical. The support structure was made of wooden poles that were driven into the ground and bent to form the rounded walls and roof. The dwellings were covered with birch bark.7

A dwelling area would have been cleared for the construction of residences. Land for agriculture would be cleared. Crops would be planted in April/May using stone or shell hoes. The forests around the dwelling area would be cleared by burning the undergrowth to make game easier to see and hunt.8 Burning the undergrowth also created open land for crops and provided the soil with nitrogen, an important fertilizer.

It’s not known how large the area that Roger and his company made use of before it was reduced to four acres. Crops grown were likely corn, squashes, beans, pumpkins, artichokes, and tobacco.9 In the 1620s-1670s, some Indigenous groups also raised domestic animals, such as pigs, to sell for cash.

The river was actively fished, especially during the alewife, salmon, and shad spawning seasons. The people had sophisticated tools including fishing nets, lines weighted with pebbles, harpoons, spears also known as leisters, hooks, and bone tools known as gorges.10 People also constructed fishing weirs, or traps, made of stone and other materials. In other towns such as Concord, Massachusetts, for example, Indigenous stone fishing weirs would later be replaced by dams in the 17th and 18th centuries.11

There’s no written record of what happened to “Roger & his company” after 1646. The Indigenous people living in the lower Merrimack River valley didn’t “disappear” after 1646, as was erroneously held as fact throughout much of the 20th century. All or some of the group may have moved north to other Pennacook-Abenaki communities in New Hampshire or near Canada. Some may have assimilated into the English population of Andover.

The 19th century idea of “the last Indian” is a false expression. Through intermarriage, some people assimilated into the English culture. Others, such as Nancy Parker, continued to live in the area, married within their community and had children who also stayed in the area.12

Indigenous people, since long before first contact to today, continue to work to maintain their communities and cultures.

It’s not known how many Indigenous groups had settled along the Shawsheen River pre-1646. Some researchers have found evidence of groundworks, that they identify as “forts,” throughout the lower Merrimack and Shawsheen Rivers, and local brooks, and ponds. It’s possible that the groundworks indicate where Indigenous settlements were located.13

Colonists settled in the same resource-rich places as the Indigenous people, there could have been settlements in what is now Ballardvale, Stevens Street, and Shawsheen Village.14

This first installment of the Shawsheen River history is a very brief introduction to the deep history of the area before 1646 - when Andover was created by the English colonists. If you would like to read more about the time period, this website lists a number of books and online resources: Native American Archival Resources for the Merrimack Valley and Beyond, on the UMass Lowell Library website.

In our next installment, we’ll look at post-1646 through 1700 and the early years of Andover.

Thanks so much for reading! Please leave a comment, like, and subscribe. You can help make History Buzz more visible to other history-loving readers.

~Elaine

Strobel, Christoph, Native Americans of New England, Praeger, 2020, p11

IBID, 13-14

IBID, 26-27

IBID, 29-30

IBID, 13-14

IBID, 13-14

The Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki website, cowasuck.org/lifestyle/shelter

IBID, 40-42

Fuess, Claude, The Story of Essex County, p60-61

IBID, 47

The University of Chicago Press Journals, journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1093/envhis/emx123

Bell, Edward, Persistence of Memories of Slavery and Emancipation in Historical Andover, Shawsheen Press, 2021, p149-150

Fuess, 43-46

Strobel, 13-14

This is a very informative post. I also like the term "deep history". "Pre-history" does not make sense when one thinks about it.

Hi Elaine,

I live over on Beacon Street next to a small brook that passes under Beacon street. We have about 6 acres of conservation land behind my home and there are many large groundworks alongside of the brook and i was always curious if they were related to the Indigenous population that were here. Do you know of anyone who could look at these to see if that's true? What were they used for? Tx

Daniel