A Botanical Education

In my recent posts, I have written about Margaret Leslie Abbott Chase and her specimen book: “The Plants of Andover.” This book is full of wildflowers and other plants, carefully pressed and glued into the book. Margaret recorded the names of each plant according to typical botanical standards, with both the Latin and common names. As I have told Margaret’s story, I became curious, as you might be too: how did Margaret learn to make a book like this in the first place?

The answer surprised me: she likely studied botany in high school.

Botany was a common hobby and a scientific pursuit for women in the nineteenth century. There were some who kept gardens, collected plants like Margaret did, created floral arrangements, and painted watercolors of vibrant flowers. And others, too, who contributed to the blossoming field of plant science, studying yet-uncatalogued plants and recording their variants. Women’s involvement in scientific botany was especially common in the beginning of the nineteenth century. 1

Margaret Abbott: a student at Punchard Free School?

In the front cover of Margaret’s specimen book are the letters “P.F.S.,” which I come believe stands for “Punchard Free School.”

We have attributed this book to being made in around 1893, which would make Margaret 18 or 19 years old — about high school age. In the early 1890s, Margaret would have lived less than a mile from Punchard Free School, and it would make sense for her to have attended.

Punchard Free School was Andover’s first public high school.2 It later became Andover High School in about 1957 when the school moved to its current building on Shawsheen Rd. At this time, the former Punchard School building served junior high school students.

Though there were other private schools in the area, Punchard was Andover’s first public secondary school — an important addition in a state highly regarded for its public education. The school takes its name from Benjamin Hanover Punchard, an Andover businessman and banker who gave the funds to found the school in his will.

Benjamin Punchard wrote, describing his vision for the school:

“Said School to be free for all youths resident in Andover, under the restrictions of the Trustees, as to age and qualifications. No sectarian influence to be used in the School; the Bible to be in daily use; and the Lord's Prayer, in which the pupils shall join audibly with the teacher, in the morning, at the opening: the said Trustees to have the sole direction; and power, also, to determine and decide whether the School shall be for males only, or for the benefit of both sexes.”3

The school was indeed built as he’d hoped, and the trustees decided to allow both men and women to attend. Punchard Free School (later Punchard High School) opened in 1856 with a ranging curriculum, including mathematics, languages, science, and “domestic arts.”4

It seems likely that Margaret Abbott attended Punchard Free School. In 1893, she lived at 14 Upland Rd, only a fifteen minute walk from the school.5

Botany classes: a precursor to biology

Today, most high schoolers take a biology class, along with chemistry and physics; these are typical ways of learning science at the secondary school level. At the end of the nineteenth century, however, biology was not yet commonly taught, nor was it consolidated as a single field.

Instead, what we now call “biology” included several diverse fields: zoology (the study of animals), physiology (the study of anatomy and living organisms), geology (the study of minerals), and botany (the study of plants). Around 1893, the National Education Association began to advocate for a more blended approach to biology, and for the “natural sciences” to be taught as much as chemistry or physics.6

Here is a typical course of study from Punchard Free School at the time that Margaret would have attended:

You may notice that the subjects are still familiar: English, History, Science, Mathematics, Art, and language study. However, looking down the science column, in the third year, students would take a class in Botany. The class was carefully timed for the Spring, when many plants would be resurfacing from the Massachusetts frosts.

This schedule is typical for a secondary school at the end of the nineteenth century. Like many other students her age, Margaret would have learned rhetoric and history, and studied botany with her peers. Perhaps, then, her specimen book was an academic assignment, or maybe it was something she enjoyed so much that she continued to study on her own outside of school.

Bringing homework to life…

Learning botany meant studying how plants work, how they grow, how they take in energy, their life cycles, and their structures. It also meant learning the different classifications of plants, so that one could understand the broader categories of the natural world as laid out in botany textbooks. We still use many of these categories today: plants have a common name as well as a Latin name according to their taxonomic classification.

Of course, like most scientific fields, there is a high school-level approach to study and a more advanced kind of lesson. In high school, students like Margaret would have been assigned a textbook to read to learn about the structure of plants and to reference the catalog of known plants.

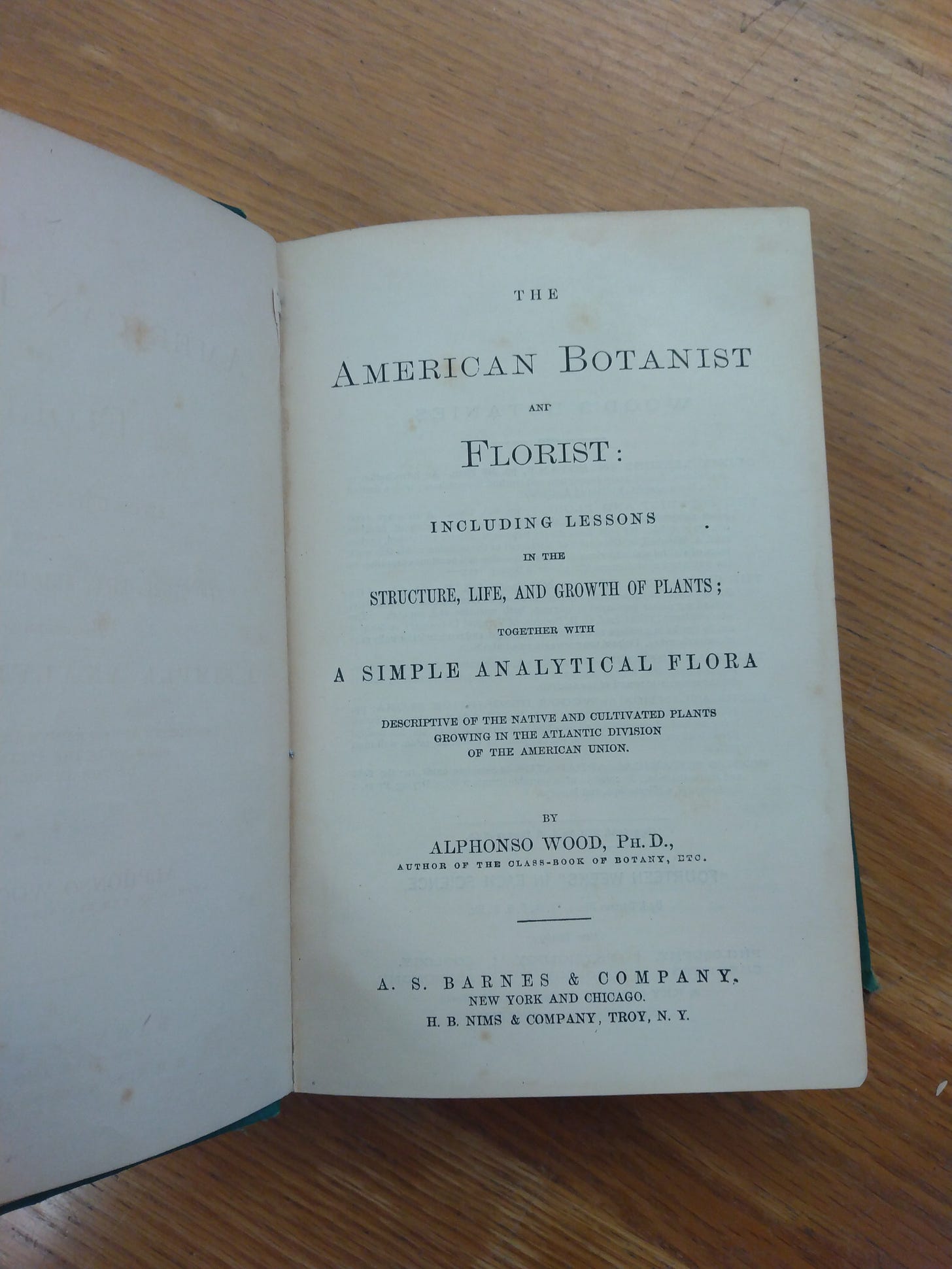

One example in our collection is Alphonso Wood’s The American Botanist and Florist: Including Lessons in the Structure, Life, and Growth of Plants (1877). This was published in New York and intended for students learning basic botany. This textbook has two connections to Andover: its author studied at the Andover Theological Seminary.

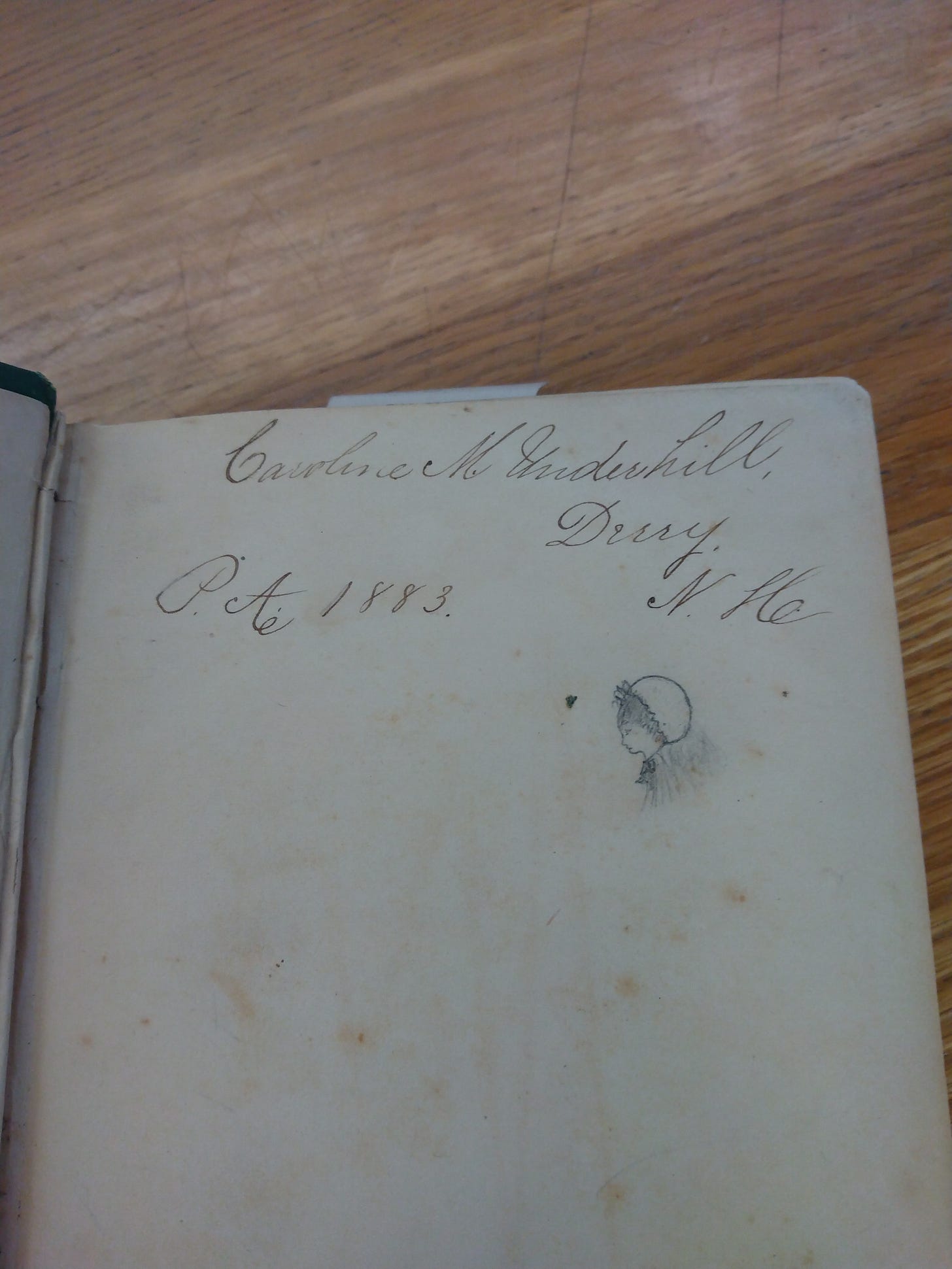

And second, our copy of the book was owned by Caroline M. Underhill. Caroline later became the resident director of the Andover Historical Society, living at 97 Main St and offering tours of our historic house.

Like Margaret Abbott, Caroline must have taken a high school course in botany with this book. Her inscription, in the opening pages of the book, includes her name and date. Caroline was 16 when she added whimsical pencil sketches and notes on homework assignments to this textbook. After high school, Caroline attended library school at Columbia College, then became the Librarian at the Utica Public Library in New York, and eventually came to Andover.

Caroline’s textbook, along with the schedule of courses at Punchard Free School, can help us imagine what Margaret Abbott’s experience studying botany might have been like. Perhaps the high school class encouraged Margaret’s interest in botany — after all, can you blame her? It’s easy to be enraptured by the beauty of the natural world.

Thank you for reading! I find it nice to imagine springtime amid wintry weather like this, and I hope you feel similarly. Comment below with your questions, thoughts, and experiences. I love to hear from you.

Plus, click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

— Toni

Dorothy B. Rosenthal and Rodger W. Bybee. “High School Biology: The Early Years.” The American Biology Teacher 50, no. 6 (1988): 345–47.