Margaret Abbott's Flowers

What can we learn about an ordinary woman's life from her flower collection?

Hello, and Happy New Year! I’m back with another botanical post to warm us up amid this chilly and rainy weather. In one of my previous posts, I wrote about Margaret Leslie Abbott’s pressed flower books, which we hold in our collection. Like many other Victorian women of the late nineteenth century, Margaret practiced amateur botany, traveling through her neighborhood to gather and preserve samples from the world around her.

As I became curious about Margaret’s specimen book, I also wanted to know about the person who had created it. What was she like? What was life like for an ordinary woman living at the turn of the twentieth century? Why did she spend her afternoons recording the lives of plants?

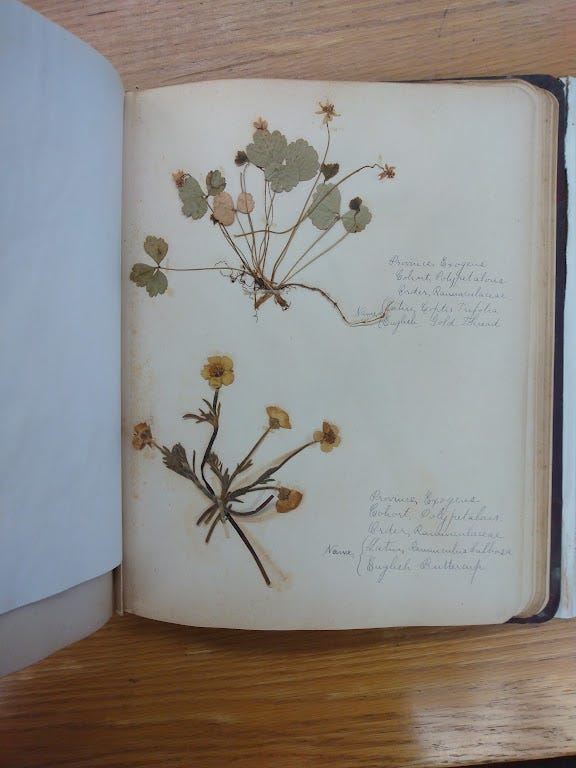

Margaret Leslie Abbott’s pressed flower book is beautiful, full of carefully preserved plants that Margaret collected from around Andover. She had documented them dutifully according to botanical research standards of the time.1

But there is still much to learn about Margaret Abbott herself, and her story demonstrates how it can be far easier to uncover histories of men than women, especially in the 19th century. As I’ll share, I hope that telling stories about her botanical practice can help us learn more about what her life might have been like.

Here are a few of the things we know: she was born in 1874 to the Abbott family.

Her parents are Nathan Foster Abbott and Margaret Edgar (Smith) Abbott. Margaret married Herbert Fairbanks Chase on January 20, 1898, when she was 24 years old.2

The Andover Townsman recorded a social announcement in March 1898, when the new Mr. and Mrs. Chase hosted a reception at their house. They offered a “most enjoyable evening” with refreshments and cocoa and many guests:

At this time, Margaret and Herbert lived at 5 Washington Avenue. It was a relatively new street and house at the time — the street itself was constructed and named in 1889. They lived at the house on Washington Street for only about a decade, and then moved to 95 Elm Street to live with Herbert’s brother, Omar, around 1903.3

Herbert Fairbanks was a successful Andover businessman. After several years working as a machinist, he opened his own shop selling and repairing bicycles.4 This photograph of the storefront from 1892 shows a bicycle wheel through the window:

The shop was one of the first tenants at 13 Barnard St, and it must have been very successful. Herbert moved the store to various locations on Main St, and eventually turned it over to William Poland, who continued to run the shop.

But what about Margaret? We know what her husband did for work, the properties he owned, and other places where his name is more visible than hers. We can even find ads documenting the locations of the bicycle shop. Some women, especially more privileged women, left behind diaries or oral histories, other ways of writing down the interesting moments of their lives.

I wonder if Margaret’s specimen book might tell us a little more about her passions. I’d like to imagine a day of her life as she set out into town in search of interesting plants to uncover and document.

As I was looking through our collection recently, I came upon a small tin box. As I continued to study it, I realized that it might have been used by Margaret. Our records note that the specimen box belonged to Omar P. Chase, Margaret’s brother-in-law, who she lived with for some time. It is certainly believable that this box would be shared with Margaret for her own botanical research.

This “vasculum” or botanical box is made of tin, like most boxes of the period. It’s wide and flat, and would have held specimens as a botanist traveled outside to collect material.5

Imagine Margaret carrying this box with her like the women pictured below, carefully storing the plants she found with a moist towel to keep the specimens fresh until she could return home and preserve them using a botanical press.

In a popular book about collecting seaweeds, the British author David Landsborough writes about how one might use a botany box:

“When the vasculum is filled, or the time is up, or the collector tired, let the spoils of the sea be carefully examined when he reaches home…Then it is that there is scope for fine taste, and for the delicate manipulation of ladies’ fingers; nature must be consulted as the sure instructress for laying out the specimens in the most graceful manner.”6

After a trip to collect plants, Margaret might have opened her specimen box like a small treasure chest and laid out all of the specimens she had gathered in an afternoon. She would have compared them to published research as she pressed and labeled them and included them in her small specimen book.

Looking at Margaret’s story through the objects she left behind cannot tell us everything about her life, but they offer more to her story than we might otherwise find printed in newspapers or left behind in business records.

Thank you for reading! You can even make your own “botany box” using some household materials — maybe you are the next documenter of the Plants of Andover! Comment below with your questions, thoughts, and experiences.

Plus, click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

Thanks for reading!

— Toni

Check out Sienna Asselin, “The Forgotten Feminine History of Botany” Verily (2019) or Matthew Wills, “When Botany was for Ladies,” Jstor Daily (2019) for a brief discussion of women in botany in this period.

Here’s an example of Charles Darwin’s botanical box at the Linnean Society.