Hello all – I’m taking off my witch hat to share a story about another topic I hold dear: botany! As we transition into Autumn, perhaps you are (like I am) watching your garden change too. As you think about the plants you care for, I invite you into the story of botany in the nineteenth century — and the women who studied and preserved it — through the 100-year-old wildflowers in Margaret Leslie Abbott’s specimen book.

— Toni

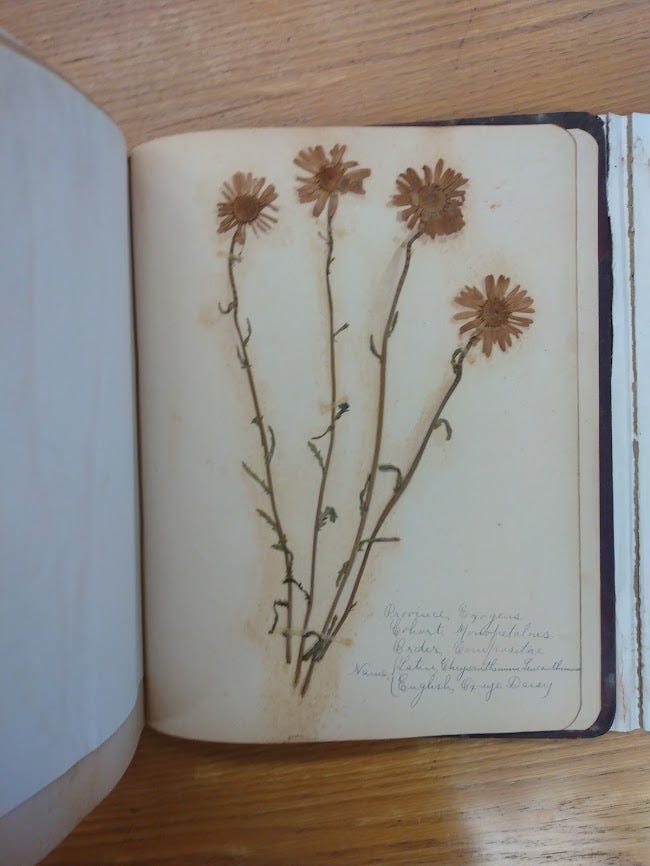

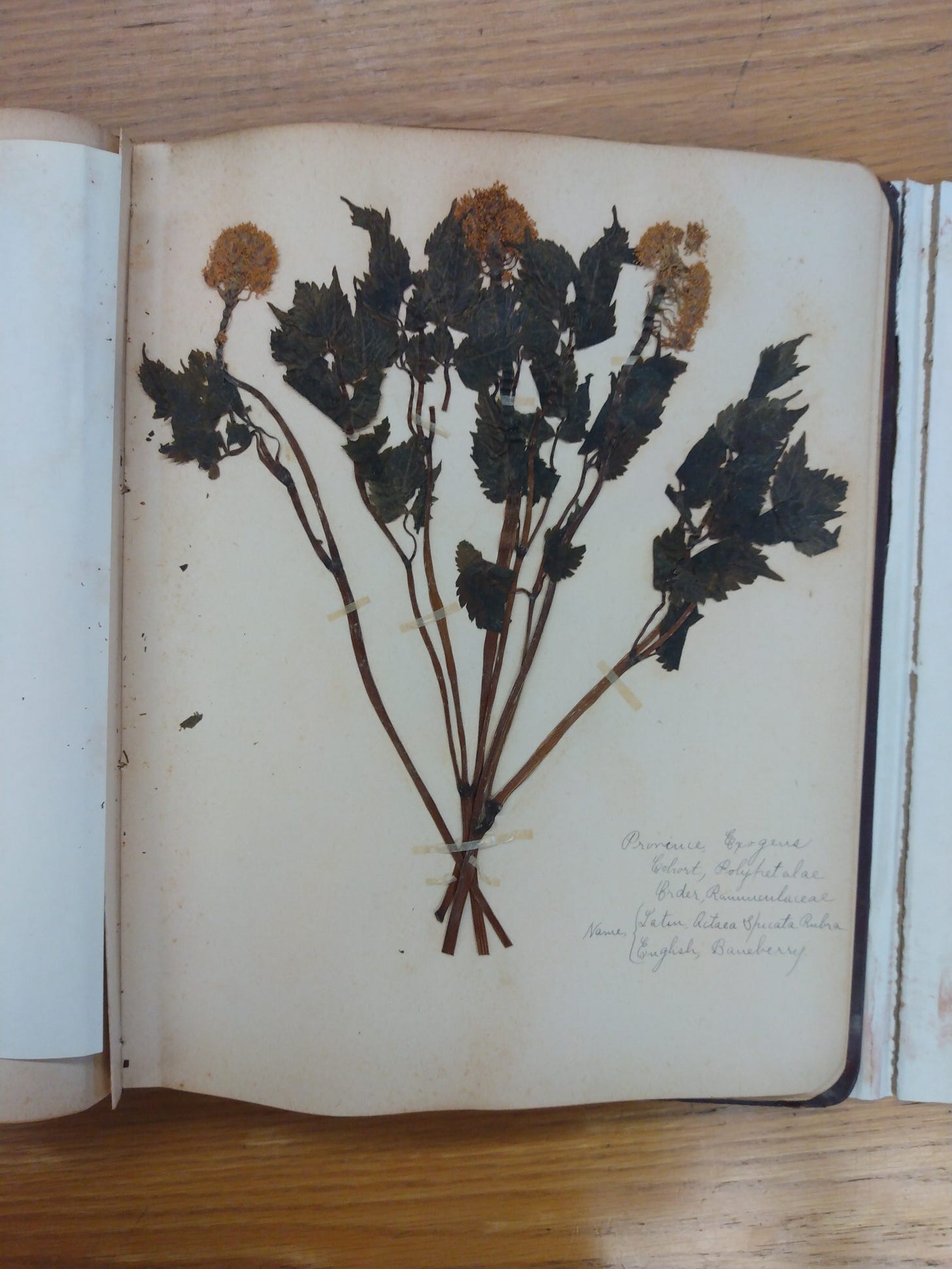

Pressed between each page of this book are flowers and plants from Andover. Margaret was careful, labeling each with their English and Latin names. The petals – over a hundred years old now — are still in excellent condition, intact, and retaining their original shapes and some color. It’s amazing to see each plant still so recognizable after the drying process and all this time.

Here’s one example:

This is the plant “chrysanthemum leucanthemum” or the oxeye daisy, a wildflower that still grows in Andover. Maybe you can find your own example in your backyard, or in a park nearby!

When in the ground (rather than preserved), the oxeye daisy has a bright yellow center and small white petals. It’s not native to Andover or to North America, but was introduced from Europe and spread quickly as an invasive species. Margaret has neatly labeled it here with the English and Latin names and the plant’s class and order according to botanical classifications.

The Emergence of Botany

Botany became very popular during the eighteenth century. During this period, many people were interested in science, not just as an academic field but as an at-home pass-time too. Men and women became interested in botany and started studying and writing about plants. It’s also at this time that major expeditions to study botany in other parts of the world took off from Spain and Europe too.1

By the end of the nineteenth century, collecting plants and making scrapbooks like this one were all the rage with women. Women read books about botany and studied painting and design so they could create watercolor illustrations of the plants they found. Women also began creating specimen books and contributing to herbaria, or large collections of living and preserved plants.2

Check it out! This is an example of a seaweed scrapbook from 1848, currently at the Brooklyn Museum3:

That’s where this book comes along. Sometimes plant scrapbooks were made for botanical study, and sometimes they were made as art, and sometimes they were meant to memorialize something.4

There are some examples of travel scrapbooks, with plants taken from someone’s adventures abroad. It makes sense! At a time when they couldn’t take photographs easily, what better way to remember something than to preserve an example of it?

Margaret Leslie Abbott’s Botanical Scrapbook

I think M. Leslie Abbott’s book is about research as well as memory. The book is labeled as the plants of Andover, so it’s not from any travels she might have taken. She’s careful to document the names and categorizations of each plant she has collected.

Perhaps we can imagine her walking through her own garden in Andover, or finding her way to others. If we go back to her oxeye daisy, this plant grows wildly and invasively. Maybe she found it growing near her lawn, and picked an example.

She would have preserved it by cleaning it, laying it out on clean paper, and then pressing it between two pages in a wooden flower press. She would have added more paper and continued tightening the pressure of the press until it dried.5

Then, she would have taped and glued it into her specimen book, arranging the plant carefully so that none of the fragile petals were damaged or folded. She wrote in pencil in the bottom corner, probably referencing botanical manuals of her era for the Latin names and Linnaean classification details.

She continued her research, searching through Andover for other examples of wildflowers and other plants to add to her book…

Thank you for reading! Do you collect plants of your own? Maybe you have your very own pressed plant scrapbook at home — I would love to hear about it. Comment below with your questions, thoughts, and experiences.

Plus, click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

Thanks for reading!

— Toni

Sienna Asselin, “The Forgotten Feminine History of Botany” Verily (2019). Also Matthew Wills, “When Botany was for Ladies,” Jstor Daily (2019). For a longer investigation into women and botany, check out Ann B. Shteir, Cultivating women, cultivating science: Flora's daughters and botany in England, 1760-1860 (Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

Thank you for the new History Buzz series, Toni! I'm looking forward to reading future installments.