Unveiling Jo March's Real-Life Counterpart: The Bookish Adventures of Abby Locke in Civil-War Era Andover

Exploring the Diary of a 14-Year-Old New England Girl, Abby Locke, Reveals a Fascinating Literary Journey Resonating with Louisa May Alcott's Iconic Character

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, hit that subscribe button to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

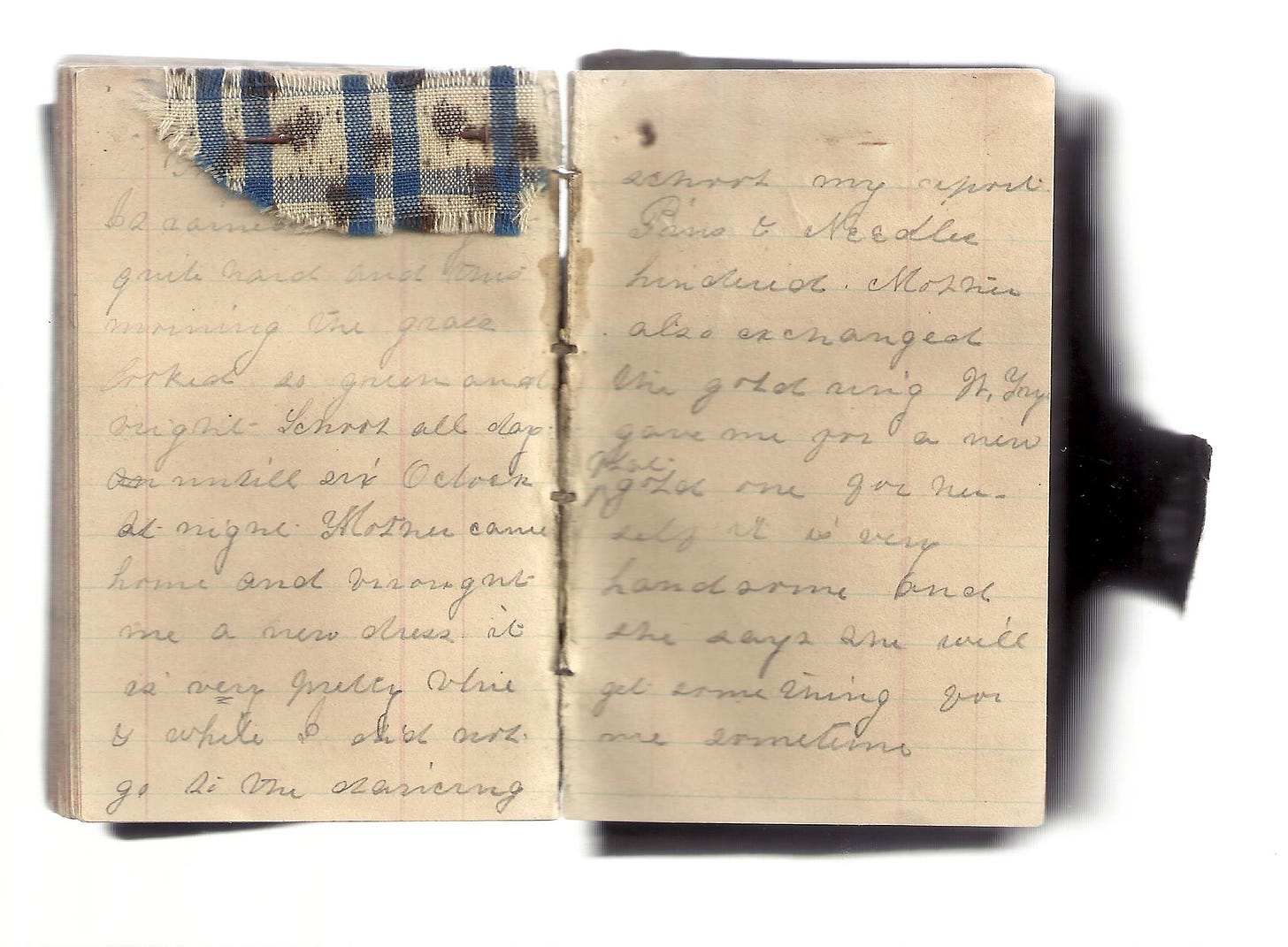

One of the most enduring fictional portraits of New England girlhood in the Civil-War era—and girlhood reading, in particular--comes from the pen of Louisa May Alcott. Who can forget the image of Jo March, munching on an apple, losing track of time and her chores, as she read in her garret and fueled her prolific imagination? In the collection of the ACHC, we have a diary of a real-life Andover girl from the same decade who, like Jo, read at an enthusiastic pace. Along with an account of her daily activities: school recitations and examinations; household chores; dancing classes; visits with friends and neighbors; and church attendance, fourteen-and-a-half year old Abby Locke kept a list of the 43 books she read during the year 1867, many of which can be positively identified as some of the best-selling titles of the era. The list includes poetry and plays, historical fiction, travelogues, moral stories or “Sunday School books,” popular page-turners, and, interestingly, more sensational or “trashy” romantic fiction than Abby’s mother (or Jo’s Marmee) might have approved.

The first book on the list is Whittier’s Snowbound (click to read for free), published as a book-length poem the February before. The second was Charles Dickens’ Dombey and Son, one of the six Dickens’ novels Abby read over the year. She wrote on January 22 that she had borrowed The Old Curiosity Shop, likely from Dow’s circulating library on Essex Street in Lawrence, since the Memorial Hall Library had not yet opened. She continued through Great Expectations, Little Dorrit, Nicholas Nickleby and Oliver Twist.

We regard these books now as weighty, PBS-worthy classics, but they were considered page-turners in the 1860s and less than respectable by some. Harriet Beecher Stowe was one person who (in an 1843 critical essay, well before she had become herself a famous novelist and had met Dickens herself) disapproved of the secular nature of Dickens’ stories, and especially the constant “tippling” or drinking of alcohol in which many of his characters indulged. But she admired him for his literary realism, and the respect he had for “our coarse common world.” She further admitted that his influence on his readers, especially young girls, was much better that that of Byron, for example, whose romantic excesses led young girls to value “terribly black whiskers and a lofty morose contempt of God and man” in their potential husbands.1 While Abby doesn’t have any poems by Byron on her 1867 list, she was probably susceptible to the sentiments. On the last of her memoranda pages, she copied a quote from his friend the poet Thomas Moore: “With mustachios that give (what we read of so oft), the dear Corsair’s expression, half savage, half soft.”

Other titles on the list that we now recognize as “classics,” were Hawthorne’s The House of Seven Gables, Essays of Elia by Charles Lamb, and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. She read Julius Caesar, but whether this was Shakespeare’s play or one of the many biographies available we cannot tell. The Odyssey appears on her list; she probably read a translation (or perhaps an excerpt in an anthology) by Alexander Pope that was regarded then as standard, since new and more accessible translations did not start appearing until later in the 19th century. Also appearing is Sir Walter Scott’s “Ivanhoe” and “The Princess,” Tennyson’s semi-comic 1847 poem about a princess who founds a women’s college.

The “Sunday School” books, written in both England and the United States, featured young people who, tested by temptation and hard times, ultimately choose the righteous path and were considered particularly appropriate for young girls approaching the age of their own moral choices. Helen Morton’s Trial and its sequel Watch and Pray or Helen’s Confirmation were semi-autobiographical stories written by Alice B. Neal Haven under the pseudonym “Cousin Alice.” George Morton and his Sister by Catherine Maria Trowbridge features a “rough, untutored” city boy who is turned from a life of delinquency. The Gayworthys: A Story of Threads and Thrums tells the story of a family in the Massachusetts town of “Hillbury” and was written by Adeline Dutton Train Whitney, a wealthy Boston conservative who became a strong opponent of women’s suffrage. Exiles in Babylon and the Shepherd of Bethlehem were both written by Charlotte Maria Tucker under the name A.L.O.E. or A Lady of England. The Dove in the Eagle’s Nest was written by Charlotte Yonge, an English writer devoted to the Church of England, who is known better for her 1853 The Heir of Redclyffe (one of the books Jo reads in Little Women). Abby read two books: Passing Clouds or Love Conquering Evil (1858) and Warfare and Work or Life’s Progress (1859) by Cycla or Ellen Clacy, whose life , as a young woman who had traveled with her brother from London to the Australian gold fields, may have been more controversial than that her heroines.

Of special interest is Gypsy’s Cousin Joy, the second in a series of four books written about spunky tomboy Gypsy Brenton by Andover’s 22-year-old Elizabeth Stuart Phelps in 1866. Phelps was not proud of these stories, in which Gypsy copes with domestic problems (most notably her messy bedroom), the pranks of her brothers, and then the trials of boarding school. In her autobiographical Chapters From a Life, Phelps classifies them as the “magazine stories, Sunday-school books, and hack work” that she did between writing “The Tenth of January,” her story for the Atlantic Monthly in 1860 on Lawrence’s Pemberton Mill disaster and “The Gates Ajar” her 1869 book about an unearthly afterlife for which she is probably best known. Later commentators, most notably Elizabeth Segal, make the case that the Gypsy books set the pattern for the engaging tomboy heroines like Jo March, Susan Coolidge’s Katy, Carol Ryrie Brink’s Caddie Woodlawn, and Laura Ingalls.2

Some books on Abby’s list, while written for adults and feature adult characters, sound the same moral themes as the books above. The Dairyman’s Daughter by the Rev. Legh Richmond, was a narrative of the deathbed religious experience experienced by England’s Elizabeth Wallbridge. A few of the historical fiction titles were set in the early Christian period including Julia of Baiae or the Days of Nero: A Story of the Martyrs (1843) by John Walker Brown, and Julian: Scenes in Judea, a purported series of letters from a Jewish observer of the events of Jesus’ life by Unitarian clergyman William Ware.

If some works on the list had less moral value than those above, they look to be entertaining and informative. Frederick the Great and His Family by Luise (or Louisa) Muhlbach is a romantic look at Prussian nobility in an age of luxury. Roba di Roma (1864) is a non-fiction account of travels in Italy by an American expatriate sculptor William Wetmore Story. Recollections of Seventy Years by Mrs. John Farrar (1865) is the life story of a Nantucket Quaker who spent most of her life in France and England. The Last Days of Pompeii by Sir Edward George Bulwer-Lytton (who had famously penned the words “It was a dark and stormy night;” to start his 1830 novel Paul Clifford) is a classic Victorian version of the tragedy of Mt. Vesuvius, told through the eyes of a rich young man, his beautiful lover, his saintly blind slave girl (also in love with him), and an brilliant but evil priest of Isis. Prue and I, by the Brook Farm transcendentalist George William Curtis, recounts the experiences and daydreams (of women, castles, boats etc.) of an elderly accountant who lives with his loyal wife (Prue) and his friend Mr. Titbottom. The Last of the Mortimers by the Scottish novelist Mrs. (Margaret) Oliphant is a tale of a pair of elderly sisters (one a spooky voluntary mute) without an obvious heir for their estate.

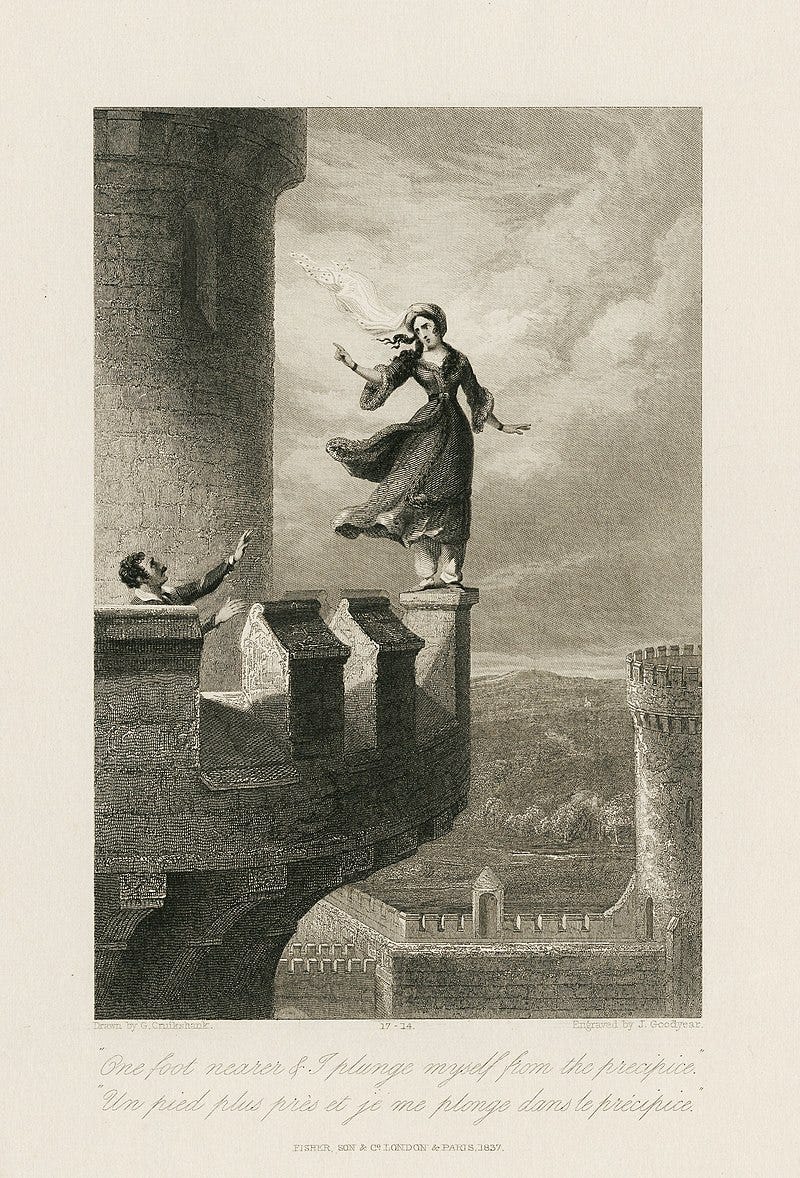

The racy romances on Abby’s list include three by Englishman Charles Reade. The first, Christie Johnstone (published in the U.S. by Boston’s prestigious Ticknor and Fields in 1859), tells the story of the virtuous Christie entranced by the young, handsome and bored Viscount Ipsden and can be seen as a direct ancestor of today’s Regency bodice-rippers. Even more eye-raising were Reade’s Love Me Little, Love Me Long and its sequel Hard Cash, which combined titillating prose with an exposé of private lunatic asylums. Held in Bondage or Granville de Vigne by Marie Louise de la Ramee under the pseudonym Ouida is a swashbuckling tale of a handsome British soldier who volunteers to fight in the Crimean War (and survives the charge of the Light Brigade) to escape the pain of loving an innocent young artist while trapped in marriage to a vengeful (but undeniably sexy) older woman.

Racy stuff, indeed.

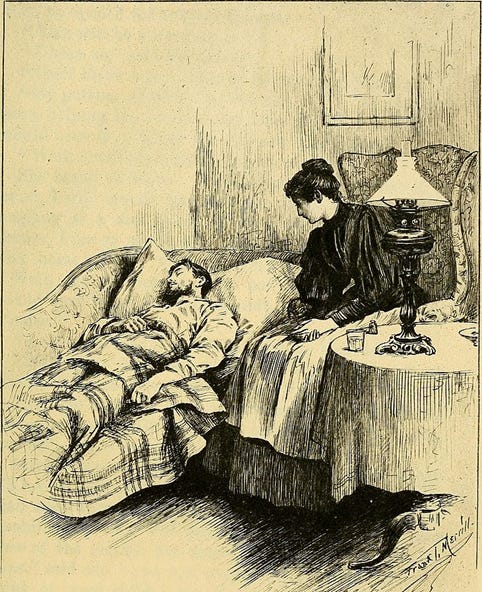

Let’s end with the image of another of Louisa May Alcott’s reading heroines, Rose Campbell, from 1875’s Rose in Bloom. Caught by her strict and protective uncle in the act of reading a “fascinating” romance, she defends herself, blushing wildly, “I really don’t see any harm in the book so far. It is by a famous author, wonderfully well written as you know, and the characters so life-like that I feel as if I should really meet them somewhere.”

“I hope not!” says her uncle.

Thanks for reading. Be a part of the History Buzz community and leave a comment, like, or share this post.

History Buzz is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

see Joan D. Hedrick, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life

Elizabeth Segal, “The Gypsy Breynton Series: Setting the Pattern for American Tomboy Heroines,” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 14 (Summer 1989):67

A fascinating insight into the literary life of a Victorian-era local teenager, and the literary landscape she inhabited.

Jane, very interesting story about Abby Locke. I didn't know she had such a long list of books. Thanks for sharing Abby's story.