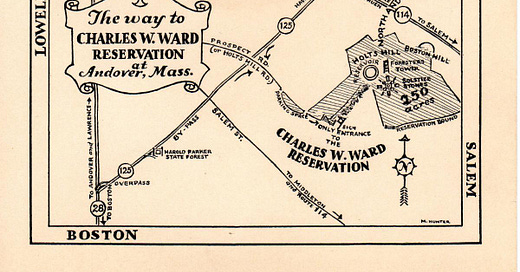

The Charles W. Ward Reservation is one of the foremost recreation areas in the region. Its history precedes Andover and requires the study of both land and people

The primary feature of the reservation is its hills: Holt, Shrub, and Boston.

The technical term for them is drumlins. Ten to twenty thousand years ago, they formed deep beneath glacial ice as meltwater deposited gravel, silt, and sand.1 The hills are very young.

For some perspective, the surrounding bedrock, appropriately named Andover granite, formed around 450 million years ago!2

Glaciers also created a kettle hole pond east of Holt Hill, known as Pine Hole Bog. Sediment buried a large chunk of ice beneath the ground. As the climate warmed, the ice chunk sunk, melted, and created a water-filled depression.3

Penacook Native Americans, one of the Algonquin peoples, settled after the glaciers receded. They traveled over much of the land but spent most of their time along waterways like the Merrimack, Shawsheen, and Skug Rivers.4 They called the area Cochichewick.5

Jump forward to 1642, when the first Europeans settled Cochichewick. They created the town of Andover in 1646, named after Andover in Hampshire, England. A land grant gave Nicholas Holt, one of the first settlers, Holt Hill and the surrounding area in 1661.

In 1714, Timothy Holt, grandson of Nicholas, built the house that now stands at 89 Prospect Road. Given its remote location, the family produced everything on-site. They had food storage closets beneath the house.

In 1775, townspeople witnessed from Holt Hill the burning of Charlestown and the Battle of Bunker Hill.

The oldest houses in Andover can often trace much of their ownership through a single family. Timothy’s descendants owned 89 Prospect Road until 1883 when they sold to Sarah L. Sawyer. In 1898, a storm damaged the house (see my article on the storm for more information).6

Charles W. Ward purchased the 173-acre estate as a summer home in 1917. He maintained a gentleman’s farm and built a cabin for the Boy Scouts that included a kitchen and Steinway grand piano.7 Charles died in 1933, but indicated he wanted to give his land to a “deserving organization."8

Seven years later, his wife Mabel fulfilled his wish and donated 156 acres to the Trustees of Reservations in his memory, thus creating the Charles W. Ward Reservation.

The original donation consisted of four parcels and stretched from Prospect Road to Shrub Hill. Mabel added to her original gift in 1944, 1946, and 1950. Most of the land consisted of abandoned orchards and livestock pastures.9

Inspired by a visit to Stonehenge, Mabel commissioned the construction of solstice stones on the summit of Holt Hill, completed in 1940. See the photo of the hill below.

The large stone slabs align with sunrise and sunset on the summer and winter solstices and spring and autumn equinoxes.10

Few of the solstice stones are from the property. The north-facing stone on the outer circle was a doorstep of a cabin on the Butterfield Farm in Andover. The cabin was a stop on the Underground Railroad. The stone to the south was the doorstep of the Stevens Tavern downtown. To the northeast is a fossilized tree fern from the Washington D.C. area, a gift from the Smithsonian.11

When Mabel died in 1956, the reservation was 280 acres in size. Her heirs formed a Land Committee to oversee the reservation. Grandson John W. Kimball served as chairman until 2015.

Under his care alongside the Trustees, the reservation grew to 704 acres with over 40 distinct parcels. The most recent acquisition was a 15-acre parcel on Salem Street from the Taft family.12

The reservation’s history allows us to have a greater appreciation for the work they’ve done.

National Snow and Ice Data Center, “Glacier Landforms: Drumlins,” All About Glaciers, National Snow and Ice Data Center, last modified March 16, 2020, https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/glaciers/gallery/drumlins.html.

Norman L. Hatch Jr., The Bedrock Geology of Massachusetts (Washington, D.C., United States Geological Survey, 1991), F11-F12, https://doi.org/10.3133/pp1366EJ.

National Park Service, “Series: Glacier Landforms: Kettles,” National Park Service, National Park Service: Department of the Interior, last modified February 22, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/articles/kettles.htm.

Warren K. Moorehead, Certain Peculiar Earthworks Near Andover, Massachusetts (Andover, The Andover Press, 1912), https://archive.org/details/certainpeculiar00moor.

Sarah Loring Bailey, Historical Sketches of Andover (Comprising the Present Towns of North Andover and Andover), Massachusetts (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1880), 2, https://archive.org/details/historicalsketch00bail.

Nancy J. Stack and Juliet Haines Mofford, “89 Prospect Rd,” Andover Historic Preservation, Andover Preservation Committee, last modified January 2011, https://preservation.mhl.org/89-prospect-rd.

John Ward Kimball, email message to the author, February 1, 2021.

Charles W. Ward, quoted in John Ward Kimball, The Charles W. Ward Reservation: A Brief Introduction to its History, Special Features, the Activities it Supports, and its Management (Andover, n.p., 2014), 4.

John Ward Kimball, The Charles W. Ward Reservation, 18-19.

Ibid, 7.

George E. Zink, Geology of the Charles W. Ward Reservation of Andover and North Andover Massachusetts (Boston, Trustees of Public Reservations, 1955), 10, https://archive.org/details/geologyofcharles0000zink.

John Ward Kimball, email message to the author, February 1, 2021.