The Plastex fire of 1941

History Buzz writer Doug Cooper shares and eyewitness account of an industrial fire in Andover's Dundee Park

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

I first came across the story of the February 23, 1941 Plastex fire while researching the Elm Square fire of 1870. Tucked away in one of the research library's vertical files, Firefighting I think, was an eyewitness account written by Robert Stefani. He wrote the account after many years spent in the wilds of New York City. I took careful shots with my phone camera and digitally filed them away for later.

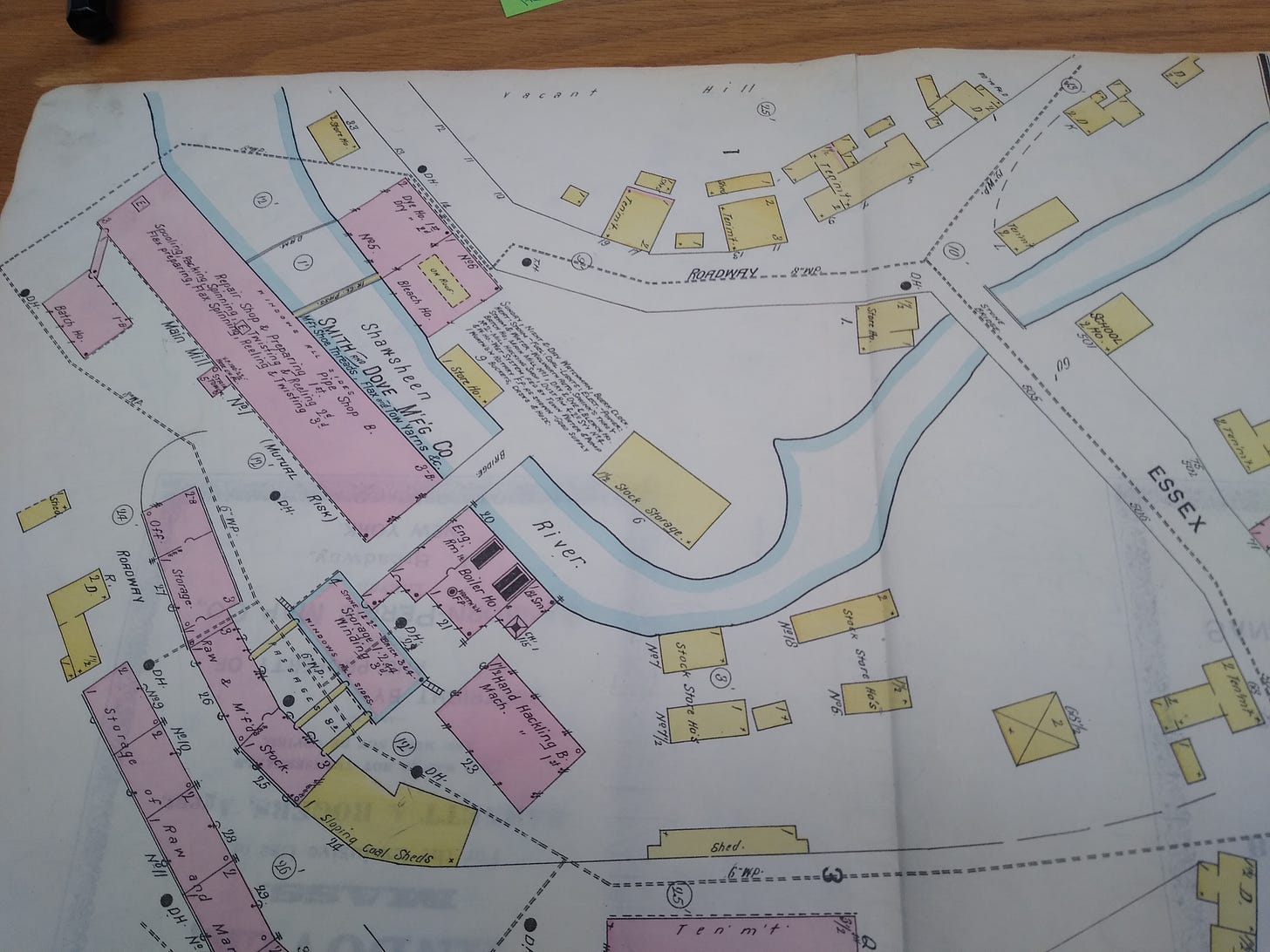

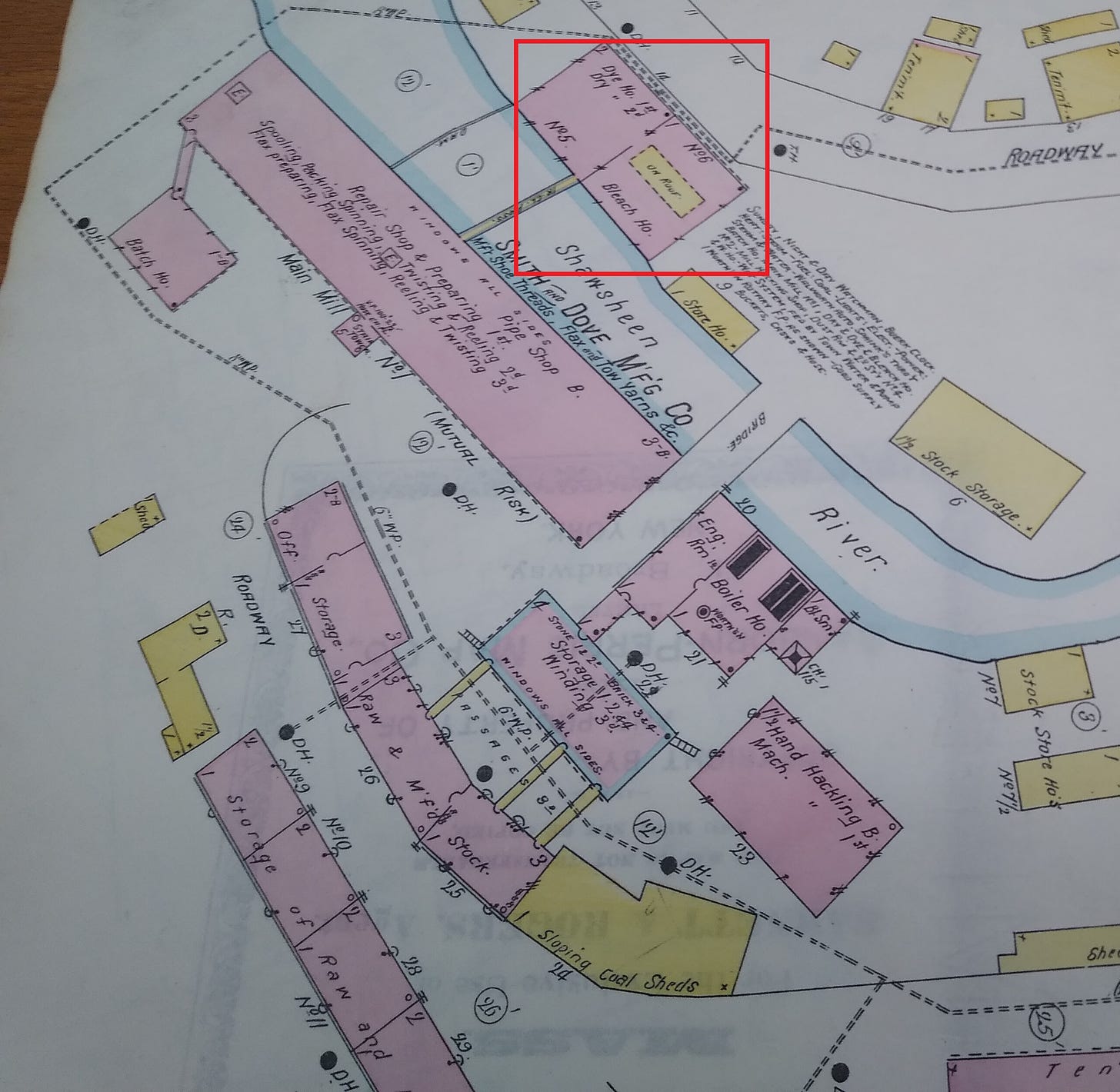

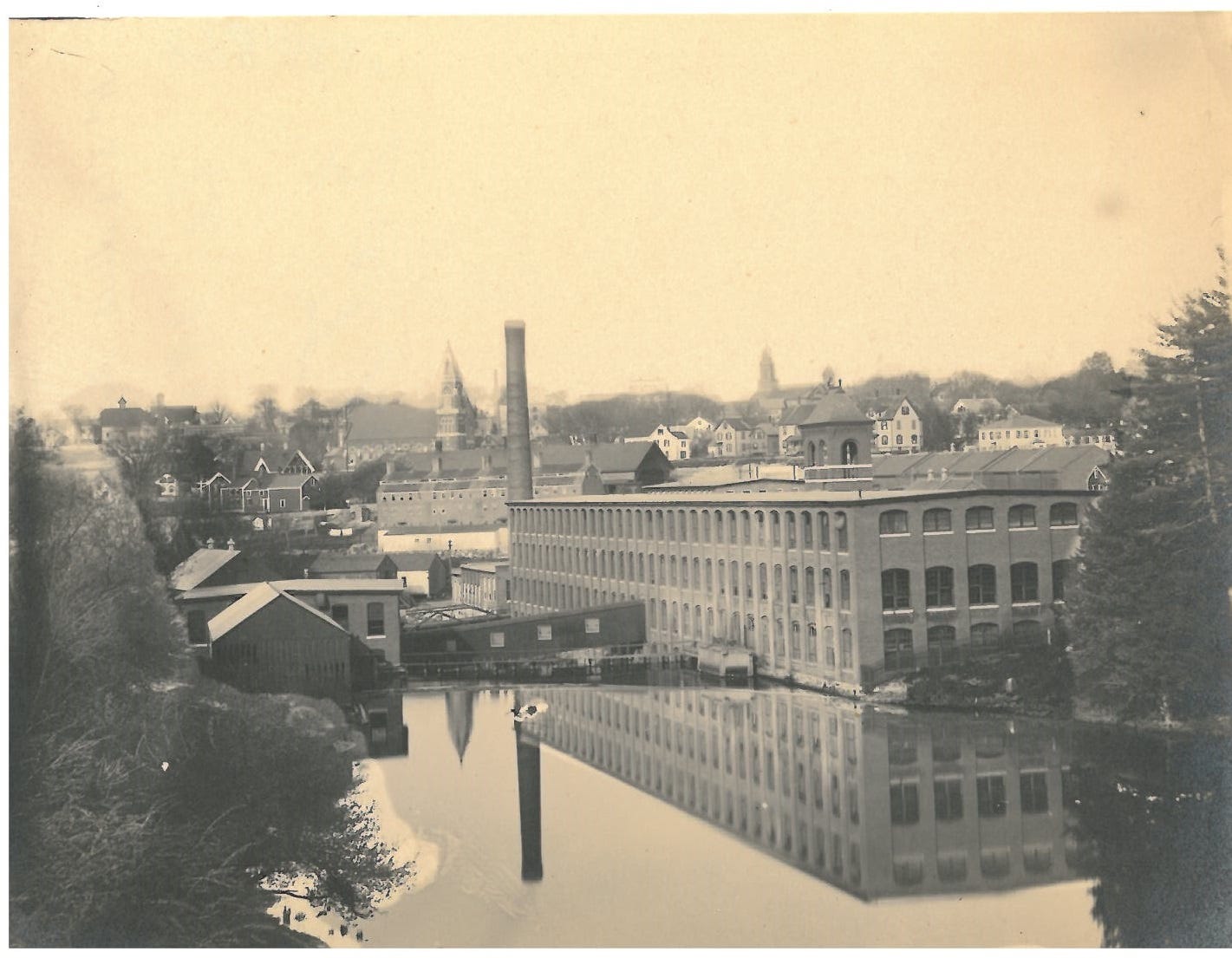

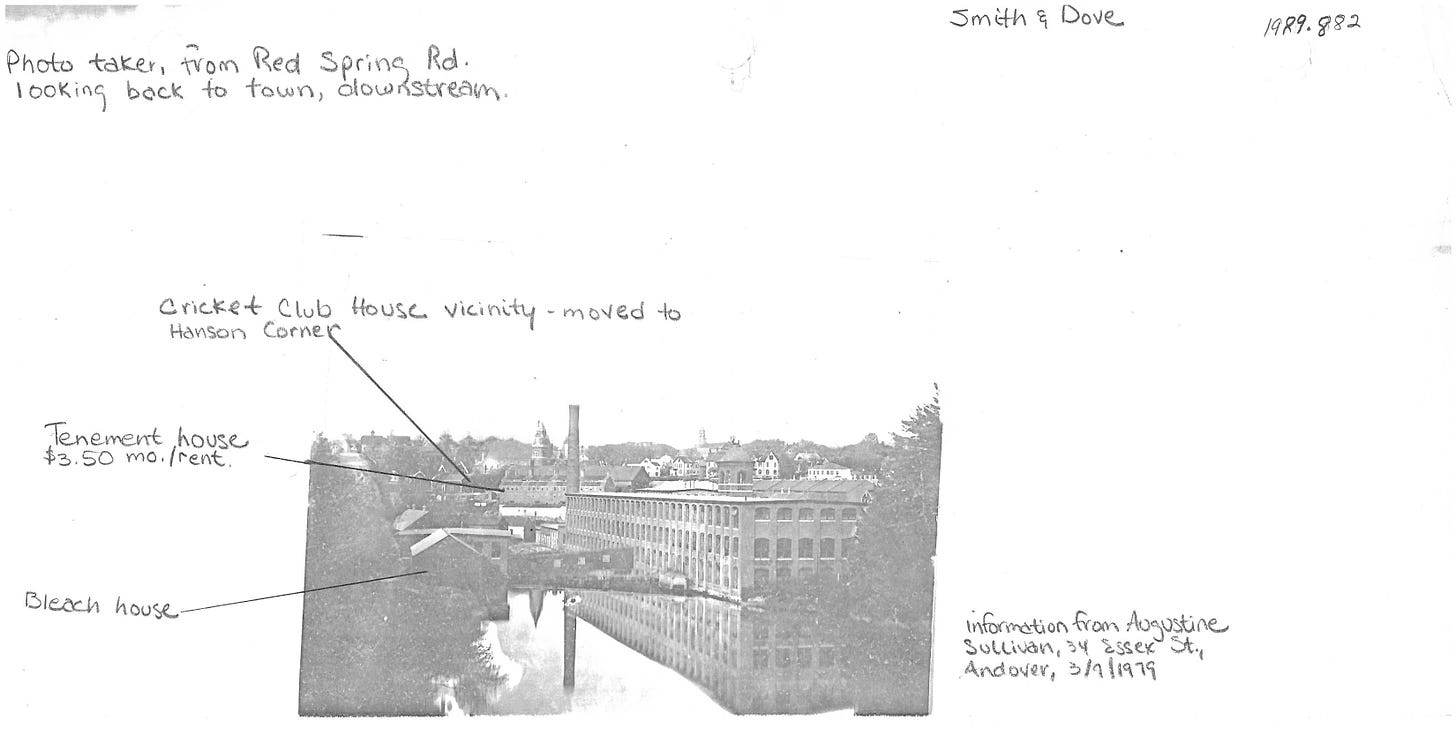

The fire happened inside the former Smith & Dove bleach house, identified as building no. 6 on the 1896 Sanborn map. The "Roadway" which the building abuts is Red Spring Road. Smith & Dove, which was an important part of Andover and the textile industry, was defunct by 1941. Their campus, today's Dundee Park, was occupied by other businesses.

My experience with Dundee Park consisted of trips into Moor & Mountain. I had no idea how big the place actually was until I started working on this post.

The Andover Townsman coverage of the 1941 Plastex fire reminded me of the 2018 Columbia Gas disaster.1 Traffic tied up everywhere! Neighboring fire departments providing assistance! Looky-loos!

After listing several trains on the Boston and Maine railroad at the time, the Townsman pointed out that “Nobody on those expresses had the least idea that they would stop in Andover.” Of the 13 fire hoses that were being used to fight the fire, four of them would cross the Boston & Maine tracks.

Andover firefighters battling the blaze were compelled to call upon the fire departments of neighboring communities. Lawrence, North Andover, Haverhill, Reading, and North Reading all sent aid. Lowell stood by in case they were needed.

A massive response was needed because several million 1941 dollars of commercial and residential property was threatened by the flames.

Heavy showers of sparks rising from the burning building were fanned by a westerly wind and some of the embers were reported to have fallen two or three miles away.

Several hundred yards away, the roof of the M.T. Stevens company caught fire, threatening over a million dollars worth of wool and cloth. Sparks found their way into the basement of a different building, the Harry J. Stephenson warehouse and repair shop. The former Smith & Dove cricket field, located near Saint Augustine's cemetery on Lupine Road, was also a casualty. All secondary fires were extinguished quickly.

And then there was the naptha.

And then there was the naptha. Three thousand gallons of the volatile chemical was stored in tanks underneath the burning building. Firemen doused the floor several times to prevent an explosion.

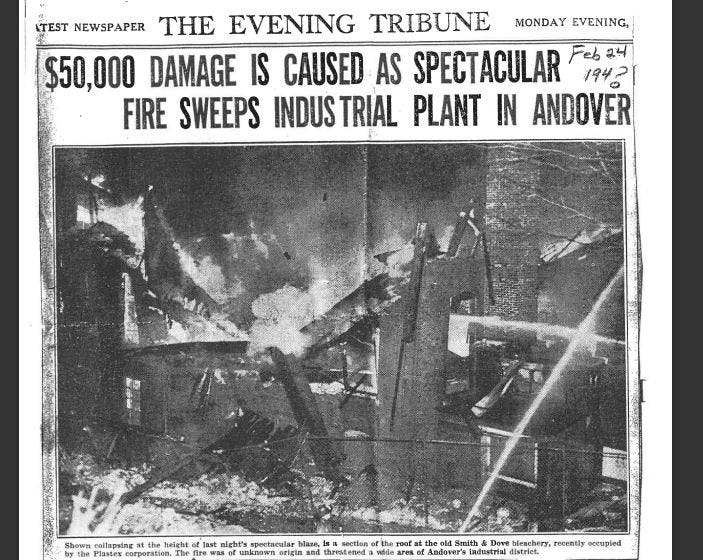

Plastex manufactured synthetic leather and rubber cement for the shoe industry. The (Lawrence) Evening Tribune reported that the fire started in the leather grinding room on the first floor of the building. "Leather shavings and dust served as fuel to give the blaze a roaring start." A section of the roof collapsing was captured by a photographer. The microfilm left much to be desired. I was thrilled to find a clearer, paper copy in the Smith & Dove vertical files.

Nobody was injured. Mercifully. Employees had worked in the building during the day, and the evening shift was yet to begin when the fire started around 5:45 pm. Plastex had only set up shop in November of 1940. Although a sprinkler system was installed in the building, it was not hooked up. The hook-up was scheduled for February 24, the day after the fire. Suspicious minds wonder if that was a story fed to journalists.

Mr. Stefani, Robert, watched this inferno from his childhood home at 41 Red Spring Road, nearly across the street. His younger brother was transfixed by a door opening and closing, “showing a flaming interior.” Robert ran back to the house to alert their mother so she could call the fire department. She must have seen the flames already, and was rushing to the phone.

If the wind shifted, the Stefani residence and the entire Indian Ridge neighborhood would have been in jeopardy. “Residents even as far away as Central Street played water on their homes because of the sparks which the wind was carrying across fields, streets and houses.”

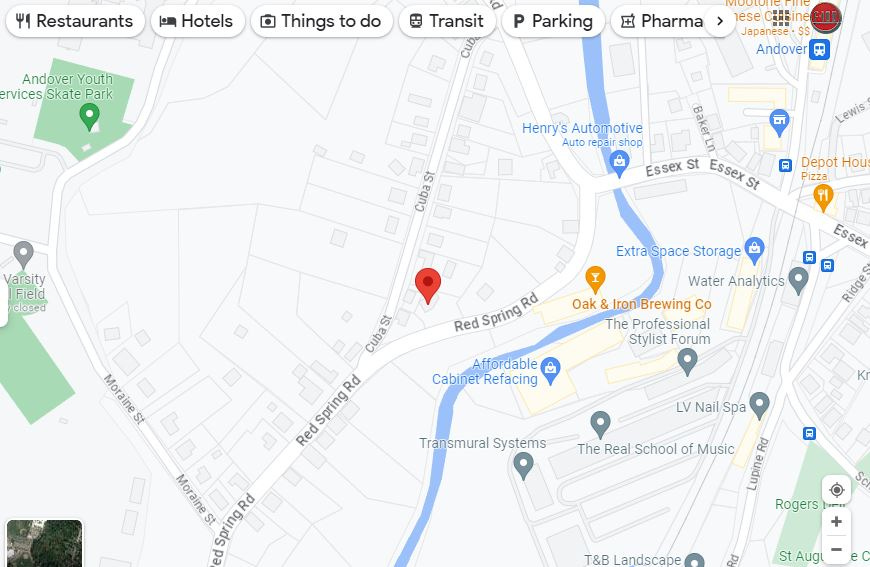

A radio news flash at 6:30pm set off a stampede of spectators. All available police officers were called in, and the state police provided assistance for crowd and traffic control. Many of the looky-loos, the Townsman reported, hovered around the railroad station or at the mouth of Red Spring Road. Today, it's the intersection of Red Spring, Shawsheen Road, and Essex Streets.

Crowd control seemed to be as big of a problem as the fire. While Robert's dad set up chairs for the neighbors to watch the blaze, spectators gathered on the frozen Shawsheen River. “It amazed me that no one ended up wet.” The Tribune noted that police shooed people onto dry land for fear that the ice would not hold their combined weight. “Steady streams of people kept coming and going from the scene late into the night."

Amateur photographers had a holiday, according to the Tribune. Documenting a disaster is deemed a holiday?

Newspaper photographers were having a difficult time and developed negatives were sometimes blank. Several "city" papers descended upon the Townsman's photographer, identified as Surette, for prints. He was first on scene. The reader can detect a bit of boasting by our hometown paper.

The Tribune story indicates that the fire took around two and a half hours to extinguish. Robert recalled that firefighters were still on duty the next morning, doing battle with periodic bursts of flames as the ruin smoldered. Likewise, the Townsman noted that “Andover's men were not completely out of there before five the next morning” and had to return. Plastex had no insurance and the building was a total loss.

ACHC's vertical files are a valuable research tool. They can be an archaeological dig. And that's not a bad thing. History Center staff member Marilyn provided me with access to the Sanborn maps, showing the location of the bleach house. But I also wanted to know what the Bleach House looked like when it stood. So I started excavating the Smith & Dove vertical files. Yes, there’s more than one.

This photo, taken from Red Spring Road, includes the bleach house. The steeples of both Saint Augustine and South Church are clearly visible. I’ve included both the photo and a photocopy of it with identifying markers.

I also found two photos of the Bleach House interior taken around 1903, complete with posing mustachioed men taking a break from their toil.

Bleaching involved the washing (and sometimes coloring) of fabric. A skein, hung from the ceiling and containing yarn or twine, would be drawn through water and bleach.

On September 13, 2018, the day of the Columbia Gas disaster, I was rolling slowly eastbound on Route 133. My initial thought was that I had caught the end of a shift at Raytheon. The weather was temperate and I had the windows down. I only heard a indistinct portion of the 21st century radio flash describing a gas explosion in Lawrence. And I was downright puzzled when a Maynard (MA), or was it Marlborough (MA), fire truck got off of I-93.

If it was mutual aid for Lawrence, I wondered, why did those firefighters come from so far afield? And why were they getting off a long way from Lawrence? I had never seen Andover traffic so gosh darn congested.

The Columbia Gas disaster was more tragic, and more costly. But, as the saying goes, history repeats itself.

Thanks for reading! Please leave a comment, like, and - if you enjoyed this post - subscribe to have History Buzz delivered to your email inbox.

~Doug

You can learn more about the 2018 gas explosions here, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merrimack_Valley_gas_explosions