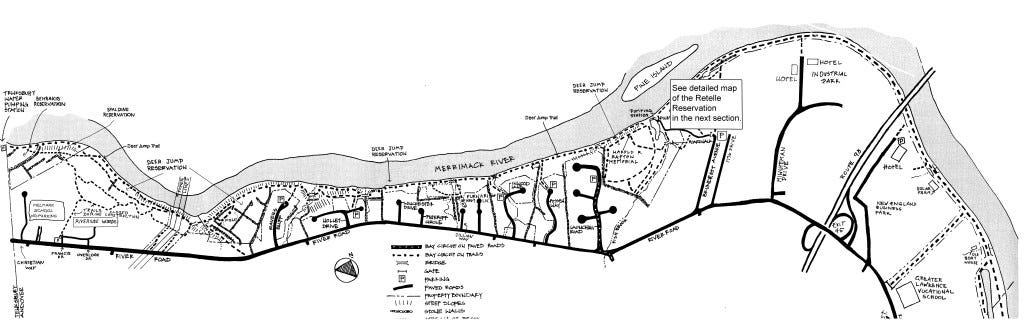

Nearly the entire bank of the Merrimack River in Andover is protected in perpetuity for conservation and recreation. Few towns have that distinction.

Map of the Deer Jump Reservation, AVIS website

Visitors traverse a long, artery-like trail over bluffs and lowlands. Extending from Tewksbury to Lawrence, there are few interruptions from its natural setting. Much of the trail lies in the Andover Village Improvement Society’s (AVIS) Deer Jump Reservation.

Penacook Native Americans settled the Merrimack River after glaciers receded.

“Merrimack” comes from the Penacook word Merruh-awke or menomack, meno meaning “island” and awke/aake meaning “place of swift current.”1

Settlements along the river consisted of villages, burial grounds, and fishing stations. The village in Andover was behind the site of the Philips Company building on Minuteman Road (formerly the Shattuck Farm) and extended to Pine Island in Methuen.23

Of course, Native Americans didn’t call the area Andover, but rather “the territory near Cochichewick,” meaning "dashing stream" or "place of the great cascade,” referring to the lake.45

Artifacts from the Penacook settlement are at the Peabody Institute at Phillips Academy. A diorama on the ground floor depicts the village on the Merrimack.6

European contact in the 17th century spelled decline for the Penacook Confederacy. Native American-European relations were not as peaceful as the story of Thanksgiving tells, and several wars brought them into conflict.

Settlers built garrisons and other fortifications, including one on the Merrimack. Native Americans attacked Andover in 1675 and 1704 and settlers retaliated.78

However, the European's most powerful weapon was disease.

The Penacook population fell from 12,000 pre-contact to 1,200 in 1675 due to smallpox, influenza, and the like. Some had a 75-100% mortality rate.9 For comparison, the mortality rate of Covid-19 is 1.2% of those who test positive in the United States.

The remaining Penacook on the Merrimack abandoned their Andover villages by 1676. They fled for safer territory upstream and in Maine.10

Settlers knew the section of Andover along the Merrimack as “Deare’s Jump” at least since 1704. There is a legend of a deer jumping from Andover to Dracut, but a namesake for an Alexander Deare is more grounded in fact.11

Following the departure of the Penacook people, the Merrimack River became an important resource for transportation and trade to Andover. The first ferry for pedestrian and commercial use dates back to c.1700. A stone foundation for a landing platform survives in the Deer Jump Reservation. While of unknown origin, ferries existed in different forms until the early 1900s.12

A notable feature of the reservation is its many stream crossings. Some powered Andover’s early grain and sawmills, including Fish Brook. Mills also took advantage of features like Deer Jump Falls.13

Deer Jump Falls was a cascade along the Merrimack. It became a local attraction by the 19th century, as told by Oliver Wendell Holmes in his poem “The School-Boy."14

Click here to read the full poem.

While the falls had recreational value, the development of the textile industry took precedent. In 1845, the Essex Company purchased Andover’s Merrimack waterfront to construct a dam for their mill city called Lawrence.

When completed, the Great Stone Dam was the largest in the world at 900 feet in length. Residents could hear the roar of the dam from miles away. The impounded water submerged Deer Jump Falls and widened the river in Andover.

The Great Stone Dam, from the collection of the Lawrence History Center #2003.012.0001

Lawrence mills thrived, but further technological advancement led to their demise. By the mid 20th century, Andover was at a crossroads between the decline of old industries and the rise of suburban development.

With suburban development came the need for open space.

Juliet Kellogg introduced to AVIS the importance of protecting Andover’s Merrimack waterfront.15 The society appointed Harold Rafton to the task.

Rafton volunteered full-time for AVIS for fifteen years. He negotiated agreements and AVIS acquired parcels of land one by one.

The first piece of land to form the Deer Jump Reservation came from the Essex Company in 1960. Most of the others came from private individuals.16

By 1973, the reservation was 129 acres. According to Rafton, this was his “most ambitious and most rewarding” work with AVIS.17

Harold Rafton, ACHC #1997.548.1

The society added the Spalding Reservation to its Merrimack frontage in 1973. The town purchased a 50-acre parcel next to Deer Jump in 1969.

An effort to provide access to the Deer Jump Reservation began within AVIS in 1960. Their efforts drew volunteers from institutions like the Boy Scouts, the Appalachian Mountain Club and Phillips Academy. Some created trails while others led hikes or talks.18

Land conservation on the Merrimack River is an ongoing effort. Both the town and AVIS purchased land as recently as 2017.19

Have you been to the Deer Jump Reservation? With its history in mind, your next walk may have a whole new dimension.

Last modified March 3, 2021.

Juliet Haines Mofford, AVIS: A History in Conservation (Andover: Andover Village Improvement Society, 1980), 171.

Ibid.

Bessie Goldsmith, Historic Houses in Andover, Massachusetts, Compiled for the Tercentenary (Andover: n.p., 1946), http://www.pa59ers.com/library/Historic/houses.html.

Leonard R. N. Ashley, What's in a Name?: Everything You Wanted to Know (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1989), 99, https://archive.org/details/whatsinnameevery00ashl.

Sarah Loring Bailey, Historical Sketches of Andover (Comprising the Present Towns of North Andover and Andover), Massachusetts (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1880), 2, https://archive.org/details/historicalsketch00bail.

Ryan Wheeler, “Students Interrogate the Peabody Dioramas,” The Peabody: The Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology (blog), August 1, 2016, https://peabody.andover.edu/2016/08/01/student-interogate-the-peabody-dioramas.

Andover Village Improvement Society, “Deer Jump Reservation,” The Andover Village Improvement Society, Andover Village Improvement Society, accessed February 22, 2021, http://avisandover.org/deer_jump.html.

Mofford, AVIS: A History in Conservation, 171-2.

Lee Sultzman, “Penacook History,” First Nations: Issues of Consequence, Lee Sultzman, accessed February 22, 2021, http://www.dickshovel.com/penna.html.

Ibid.

Mofford, AVIS: A History in Conservation, 171.

Ibid, 172.

Ibid, 171.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, The School-Boy (Boston: Houghton, Osgood and Company, 1879), 61, https://archive.org/details/schoolboy00holmrich.

Mofford, AVIS: A History in Conservation, 101.

Ibid, 173-6.

Harold Robert Rafton, “AVIS Land Acquisitions,” n.p., n.d., quoted in Mofford, AVIS: A History in Conservation, 175.

Mofford, AVIS: A History in Conservation, 177-81.

Susan Stott, “Update on Purchase of Property on the Merrimack River,” AVIS Update 124, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 1, http://avisandover.org/assets/docs/Fall-2017-Newsletter.pdf.