Pieces of the puzzle: Teasing out the history of 1646 and Andover’s Town Seal, part 3

Every town and city in Massachusetts must have an official town seal. Images on many town seals are under scrutiny. Andover's town seal is among those being evaluated.

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz. If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

Today is part 3 of our series on Andover’s town seal and the history of the English settlement of the area in 1646. Click here to read part 1 where you can read an introduction to the issues surrounding Andover’s seal, and a history of the imagery used on the seal. Click here to read part 2 where you can read an introduction to the Indigenous people who called Cochichawicke home prior to English settlement.

In today’s post, we’re looking for answers to our second and third research questions.

1. Who were the Native residents of Cochichawicke, the “Indian called Roger and his company?” (Included in part 2)

2. Why did Cutchamashe, who was a Massachusets sagamore (based in the area now known as Dorchester, south of Boston), attest that he accepted the money and coat from Woodbridge?

3. Why didn’t a more local leader appear in court to acknowledge the sale?

As we ended our post last Monday

By 1640, suffering population loss from multiple epidemics and the loss of land to English settlers, the bands of Essex County including those from the Pawtucket and other local villages joined Passaconaway’s powerful New Hampshire Pennacook Confederacy.

The band living in Cochichawicke – identified in the court document as “the Indian named Roger and his company” – were also part of the Pennacook Confederacy.

Who was Passaconaway?

Passaconaway was born between 1550 and 1570, and died in 1669, when he was said to be between 100 and 120 years old.

Passaconaway was a highly respected and charismatic Bashaba (leader) who led the Confederacy c.1610-c.1660. The Confederacy included up to 18 distinct bands and villages. It stretched from the Connecticut and Merrimack River Valleys of southern New Hampshire and northern Massachusetts to coastal New England, north to Lake Winipesaukee. The Confederacy provided access to seasonal resources, trade partnerships, and common defense.1

As Bashaba, Passaconaway, who was also a spiritual leader of his people, was believed to have magical powers. Numerous accounts were written by English settlers about his powers. One such account was written by Thomas Hutchinson in his History of Massachusetts Bay;2

Passaconaway, a great sagamore upon Merrimack River, was the most celebrated powow in the country. [They believed] that he could made water burn, rocks move and trees dance. And metamorphose himself into a flaming man, that in winter he could raise a green leaf out of the ashes of a dry one, and produce a living snake from the skin of' a dead one.

Another 17th century English account, written by Daniel Gookin,3 describes Indigenous spiritual leaders.

These are partly wizards and witches, holding familiarity with Satan, that evil one; and partly physicians, and make use, at least in show, of herbs and roots, for curing the sick and diseased. These are sent for by the sick and wounded; and by their diabolical spells, mutterings, exorcisms, they seems to do wonders. They use extraordinary strange motions of their bodies, insomuch that they will sweat until they foam; and thus continue for some hours together, stroking and hovering over the sick. Sometimes broken bones have been set, wounds healed, sick recovered; but together therewith they sometimes use external applications of herbs, roots, splintering and binding up the wounds.

Historian and archaeologist Dennis Chesley noted that “Colonial writers witnessing the demonstrations generally were avid believers in superstition, witchcaft, and the like and were easily swayed. Together these facts help explain the astounding testimonies” about Pasaconaway’s powers.4

As evidence of his widespread leadership, in 1629, the names of Passaconaway and two other tribal leaders appeared on what is called “the Wheelwright deed.” This questionable deed gave title to the lands between the Piscataqua and Merrimack Rivers from the coast to the Pawtucket falls (in Lowell). According to the deed, Passaconaway was compensated by “compitent valuation in coats, shirts, and victuals,” along with promised protections from other tribes and “free Liberty of Hunting, fishing, and fowling.” Townships lying within these lands were to present "one Coate of Trucking Cloathe" to Passaconaway if he demanded it.5

There’s evidence that Passaconaway believed that the Native people and English settlers could live together in peace, and that he worked to achieve that. That trust and peace, however, did not materialize.

By 1642, the relationship between Passaconaway and the English settler government had deteriorated.6

Governor John Winthrop’s journal says that in 1642 Massachusetts authorities acting in fear of an Indian scare reported from Connecticut ordered disarmament of Indians in their Jurisdiction.

On a rainy Sabbath in July they sent 40 armed men out to subdue the benevolent old Passaconaway. The storms severity, however, restrained their progress toward his wigwam, so the posse instead seized his son, Wonalancet, along with the latter’s wife and child. Wonalancet was disgracefully led by a line to prevent his escape, but he managed to slip out and flee. One of the captors took a wild shot at him which narrowly missed.

The court in Boston felt that Passaconaway would view these indiscriminate proceedings as “a manifest injury,” and therefore sent out Cutshamekin to bring in the Bashaba for an apology. He sent back the reply that only when his family was safe again would he listen. “Accordingly about a fortnight after, he sent his eldest son to us, who delivered up his guns…”7

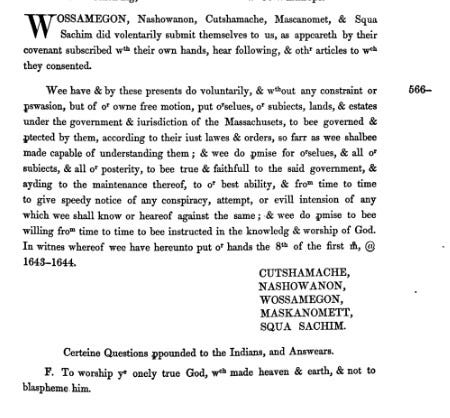

Two years later, in 1644, in exchange for the release of his son, Passaconaway agreed to what is called “a treaty of submission” in the Massachusetts Court in exchange for what was promised to be protections from assault from Mohawk tribes. Native leaders of five tribes signed the agreement. In exchange for protection that never materialized, Passaconaway agreed that the people in the Confederacy would become Christians, observe the Sabbath, refrain from certain behaviors, and remain neutral in any future conflict between colonists and Indigenous people.

The agreement was not one the tribal leaders entered into willingly. The incident convinced Passaconnaway that the English settlers and Native people could not live together, and afterwards he kept his distance from them.

With that background, we can dive into our next research questions

If the Native people who lived in Cochichawicke were a Pawtucket band organized as part of the Pennacook Confederacy under Passaconaway, why did Cutchamache, a Massachuset based in what is now Dorchester, appear in court and attest to accepting payment for the land deal?

Why was Passaconaway not mentioned in the 1646 Court document?

In 1646, Passaconaway, aged 90+, was the leader of an alliance that stretched across eastern New England.

Although Passaconaway likely would have had to give consent to the sale of Cochichawicke, given the vastness of the Confederacy, his soured relationship with the colonists after the kidnapping of his son, and his advanced age, it’s possible someone else – perhaps someone closer to Boston – appeared in court for the attestation.

This happened in other instances. For example, the 1644 subordination agreement described earlier, as it appears in court records, does not include Passaconaway’s name.

Signers included Cutchamache (Neponset band, Massachuset), Nashacowam (Nashua band, Pennacook), Wassamagin (Wachuset band, Nipuc), Masconomet (Pawtucket,) and Nanepashemet’s widow recorded as Sqa Sachim.

Based on this, is appears that Nashacowan, of the Nashua Pennacook band, signed on behalf of Passaconaway, who had given his consent to the agreement.

Cutchamache, a Neponset Massachuset, was also a signer of the agreement.

In fact, Cutchamache appears in other 17th century English records, indicating that he was active throughout the area and in the courts.

You might have noticed the name Cutshamekin/Cutchamache in the quote above.

The Massachusetts court “sent out Cutshamekin to bring in the Bashaba for an apology.”8

From this it appears that Cutchamache was working for or with the Massachusetts courts.

Why did Cutshamache make the attestation in court that he had accepted the payment for Cochichawicke?

It’s possible that Cutchamache – due to his proximity to the Boston courts, or his experience with the courts – was there as a representative of Passaconaway and the Pennacook Confederacy. It’s also possible that the record of the attestation was incorrect, based on differences in language, experience, and power. It’s also highly possible he was there through coercion.

Or, given the quote above, Cutshamache might have been working for the Massachusetts courts.

If any of that is true, then Cutshamache himself was less important in the land transfer than has been inferred from the 1646 court document. It might be that he was simply the person who was able to be at court that day to make the attestation. Or he could have been coerced into or perhaps paid for making the attestation.

Conclusions after reading, as it relates to Andover’s Town Seal

The 1646 attestation is just one piece of a very complex story about the clash of cultures.

Given the complicated relationships among and between the Native people of Essex County and eastern Massachusetts and the English settlers, the founding of Andover is less about the individual who appeared in court – Cutchamache – and more about the relationships between the people – Native and English – and the land.

Land exchanges – although “legal” by English law and recorded in court documents – were as inherently one-sided as the power dynamic between the two groups. Land was “sold” at vastly low prices, often as a result of coercion.

“Six pounds and a coat” was a vastly devalued price to pay for the land and the “forever” rights outlined in the 1646 court document.

This is a larger, more informative, and far more interesting story to tell than a late 19th century version of history that was based on the available evidence, attitudes, and understandings of the time.

Some have expressed concerns that changing the image on the seal will erase part of Andover's history . . . that it will erase the presence of the Pennacook-Abenaki who called this area home long before the English settlers arrived.

However, there’s a larger, complex, and nuanced story that needs to be told and taught – in schools and in the public sphere.

In museums, when deciding how to share information, we ask ourselves, "Is this the right medium for the message?" Sometimes an exhibit is the best medium for sharing a story. Sometimes the written word, and other times the spoken word.

In the case of Andover’s Town Seal, we can ask the same question, “Is a town seal the most appropriate way to tell this story?

Another way to look at it is:

Can we find a more appropriate medium for ensuring that the story is told as broadly as possible, in all its human complexity?

Is there a more appropriate medium for sharing and celebrating the history of the Native people who lived here centuries ago through to today?

It's a decision the people of the Town of Andover will make when the questions come before them at Town Meeting.

Thanks so much for reading. This is a deep and complex issue facing, not only the town of Andover, but many other Massachusetts towns and cities as well. Please leave a comment and participate in the conversation.

The conversation about Andover’s Town Seal is ongoing. You can follow the work of the Town Seal Review Committee on the town website. For more information, you can watch the community forum that took place in September 2022. I also encourage readers to explore the history and culture of the Pennacook-Abenaki people on their website.

Thank you to Jim Batchelder for sharing Dennis Chesley’s article with me!

Best regards

~Elaine

If you can, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to History Buzz. Your subscription - $5/month or $60/year - supports the research and writing that makes History Buzz possible. Thank you!

https://exhibits.nhd.uscourts.gov/2.htm

Chesley, Dennis, “Passaconway: a mighty Bashaba, part 1,” published by the New Hampshire Times, February 5, 1975

IBID

IBID

IBID

IBID

If the image on the seal looks more like the great plains, I believe that the Pennacook-Abenaki are misrepresented.

This is the most detailed account of the origin story I have encountered. It is indeed a complex past, not amenable to a single image if fairness is the objective.