Pieces of the puzzle: Teasing out the history of 1646 and Andover’s Town Seal, part 2, asking questions and searching for answers

Every town and city in Massachusetts must have an official town seal. Images on many town seals are under scrutiny. Andover's town seal is among those being evaluated.

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz. If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

Today is part 2 of our series on Andover’s town seal and the history of the English settlement of the area in 1646. You can read part 1 here. Part 1 includes an introduction to the issues surrounding Andover’s seal, and a history of the imagery used on the seal.

In today’s post, we’re looking at the history that the current town seal purports to tell.1 Any discussion about Andover’s town seal must begin with the image on the seal.

Our story begins . . .

The story behind the souvenir pin, and the 120 or so years of town seal images that follow, is Andover’s origin story.

According to an attestation in the Massachusetts court in 1646, the Sagamore Cutchamache sold the land of Cochichawicke to John Woodbridge, minister of the church, for 6£ and a coat, creating the Town of Andover.

The origin story was celebrated on the 1896 souvenir pin and on Andover’s town seal since 1900.

Let’s begin with the attestation

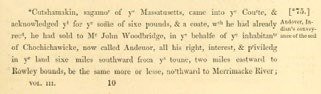

Cutshamache, sagamore of the Masschusets, came into the Court, and acknowledged that for the sum of 6 pounds & a coat, which he had already received, he had sold to Mr. John Woodbridge, in behalf of the inhabitants of Cochichawicke, now called Andover, all his right, interest, and privilege in the land six miles southward from the town, two miles eastward to Rowley bounds, be the same more or less, northward to Merrimack River, provided that the Indian called Roger & his company may have liberty to take alewifes in Cochichawick River, for their own eating; but if they either spoil or steal any corn or other fruit, to any considerable value, of the inhabitants there, this liberty of taking fish shall forever cease; and the said Roger is still to enjoy four acres of ground where now he plants. This purchase the Court allows of, and have granted the said land to belong to the said plantation forever, to be ordered and disposed of by them, reserving liberty to the Court to lay two miles square of their southerly bounds to any town or village that hereafter may be erected thereabouts, if so they see cause.

It’s important to keep in mind that documents such as this are the beginning of the story not the end.

What gets recorded in written court documents is a piece of the puzzle, not the whole picture. Records are often one-sided, and at this time, reflected the settlers’ point of view. Also, what’s missing from court documents is context and the human side of the story. 17th century written court documents reflect the English settlers’ ways of living and organizing, not the ways of the Native Abenaki people.

Some of the questions raised by the 1646 Attestation include:

1. Who were the Native residents of Cochichawicke, the “Indian called Roger and his company?”

2. Why did Cutchamashe, who was a Massachusets sagamore (based in the area now known as Dorchester, south of Boston), attest that he accepted the money and coat from Woodbridge?

3. Why didn’t a more local leader appear in court to acknowledge the sale?

My theory after reading and researching is that Cutshamache himself was actually a minor player in the story, so his prominence in the town’s origin story and the seal is misplaced.

The story of 1646, the local Indigenous people, and the English settlers is much broader and deeper than what appears in the court document - and therefore on the town seal.

Who were the Native residents of Cochichwicke?

Between 1300 and 1700, the people living in what is now Essex County were Western-Algonquin speaking Pennacook-Abenaki bands that had expanded south.2 The Merrimack River, and Cochichawicke were at the southern edge of the Pennacook-Abenaki lands, which they call "N'dakinna."3

Along the Merrimack River, in what is now Lowell, Mass., was a large village and trading center called Pawtucket. The English settlers mistakenly assumed that people living in different villages were entirely different tribes. They referred to the Native people living in the Merrimack River area as “the Pawtucket,” as they did with other Merrimack River Valley and Essex County villages, including Agawam and Wamesit.

Through marriage and trade villagers and bands established alliances among themselves and with the Pennacook, Abenaki, and other neighboring groups, including Nipmuc and Massachuset. They also joined larger confederacies for defense, warfare, trade, and other reasons. The boundaries of homelands and the constituencies of alliances and confederations were fluid and constantly changed.

The Abenaki were a farming society that supplemented agriculture with hunting and gathering. Generally, the men were the hunters. The women tended the fields and grew the crops. In their fields, they planted the crops in groups of "sisters". The three sisters were grown together: the stalk of corn supported the beans, and squash or pumpkins provided ground cover and reduced weeds. The men would hunt bears, deer, fish, and birds.4

The Abenaki’s way of living was inherently different from the English settlers’ ways. For example, instead of being organized into divisions that could be neatly mapped with clear, unmovable boundaries (cities, towns, counties, etc.). The Abenaki were organized into bands that were fluid depending on marriage and familial alliances, and strategies of leaders.

In addition, the local Abenaki society was matrilineal. Leadership and power were shared between female and male head speakers. For example, the sagamore Nanepashamet, who had residences in southern Essex and Middlesex Counties, was killed in 1619 and his widow Saunkskwa took his place as leader.

The suffix “skwa” indicates the feminization of a word, so Saunkskwa, was the female speaker for the people of their band.5

An unknown number of Native people had died in at least 8 known epidemics starting in 1564. It’s estimated to have been between 50% and 90% of the population. The epidemics left vast holes in the Native community – in personal lives, families, and in leaders and alliances.

Throughout the 17th century, the French, Dutch, and English fought for control of North America. It’s a struggle they continually pulled the Native people into. Native wars and conflicts, such as between the Pennacook and Mohawk, were part of the mix as well. Some of these conflicts between Native groups were pre-existing rivalries, others were instigated and encouraged by the French, Dutch, and English to divide and weaken the Native population.

The land loss experienced by Native people exemplifies the power dynamics between Native people and English colonists. Some land was purchased legally, according to English law, but most often vastly undervalued. Some land was acquired through questionable, coercive, fraudulent, or corrupt means.

By 1640, suffering population loss from multiple epidemics and the loss of land to English settlers, the bands of Essex County including those from the Pawtucket and other local villages joined Passaconaway’s powerful New Hampshire Pennacook Confederacy.

The band living in Cochichawicke – identified in the court document as “the Indian named Roger and his company” – were also part of the Pennacook Confederacy.

In my next post, we’ll dive into the Pennacook Confederacy, its charismatic leader Passaconawy, and the history of 1646.

Please leave us a comment, ask questions, and be a part of the conversation. We love hearing from History Buzz readers.

Thanks for reading!

~Elaine

If you can, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to History Buzz. Your subscription - $5/month or $60/year - supports the research and writing that makes History Buzz possible. Thank you!

For this post, I relied heavily on the work of a number of historians’ and writers’ published and unpublished writings.

Denise K. Pouliot, the Sag8moskwa (Female Head Speaker) of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People

Paul Pouliot, the Sag8mos (Male Head Speaker) of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People

Christoph Stroebel, UMass Lowell

Ryan Wheeler, Peabody Institute of Archaeology

Mary Ellen Lepionka, Historic Ipswich

Carol Majahad and Inga Larsen, North Andover Historical Society

Hidden in Plain Sight, North Parish, North Andover

Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People - Homelands: https://cowasuck.org/homelands

IBID

IBID

https://cowasuck.org/

Great history lesson of the local area Indian tribes