Long Memories: A history of Andover in ten (or so) trees

“Sometime around 1645...” Today, new History Buzz contributor Jane Cairns shares the eye-opening history of "Jack's apple tree." The story of Andover's first apple tree spans the Atlantic Ocean.

Who doesn’t love trees? They give us shade, purify our air and water, and provide homes for wildlife. They often provide the background to our favorite memories and, as recent research suggests, even boost our mental and physical health. As we look to them as examples of towering strength and old wisdom, they are also a useful metaphor to explore how scenes and episodes from one town’s history are interconnected with the larger world. Beginning this month, I’ll share stories of some of Andover’s best-known trees as well as the people who loved, planted and nurtured them. Enjoy!

The First Apple Tree in Andover

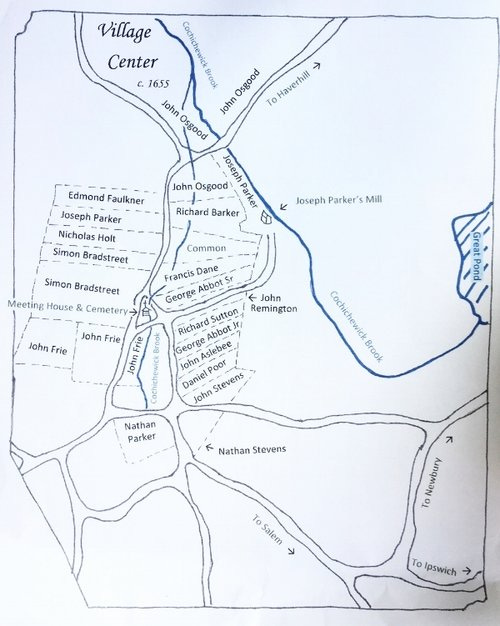

Sometime around 1645, the story goes, a Black man nestled an apple seedling into cultivated soil near the center of the new Andover settlement. His name was Jack, according to old town lore recorded by nineteenth-century historian Charlotte Helen Abbott1, and the tree was his “individual effort.” Jack (the only name we have) is said to have been the town’s first “servant”—the era’s prevailing euphemism for an enslaved person—brought to Andover from Ipswich by the town’s wealthy and politically ambitious magistrate Simon Bradstreet and his wife Anne, soon to become the first published poet in England’s North American colonies. Jack’s death was recorded thirty-eight years later in 1683.

So, who was “Jack?”

He was almost certainly African.

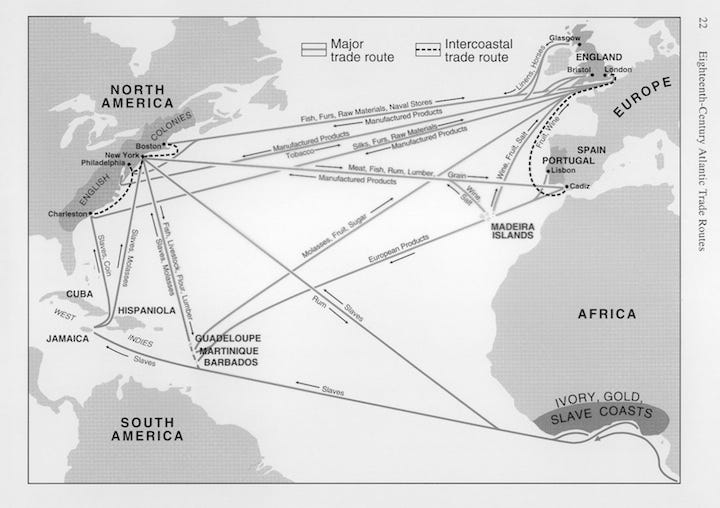

The first enslaved people imported directly from Africa arrived in Massachusetts in 1634, and in 1638 a ship named Desire brought the first shipment of Africans exchanged in Barbados for enslaved Pequots from New England. The first law legalizing slavery in North America was passed by the Massachusetts General Court in 1641 and the regular “triangular” trade of slaves, molasses and rum between Africa, the West Indies and Boston began in 1644.2

He was likely a farm hand or laborer.

The Bradstreets had five children and several domestic servants in 1645 when they moved to Andover, then a remote frontier town where Simon could accumulate more land and power. As was typical in early New England, the family and servants lived together in a small, likely four-room, cabin while their larger, more comfortable mansion across from the Meeting House was built. In addition, one of Bradstreet’s first priorities, perhaps even more urgent than his own house, was construction of a saw and grist mill on the Cochichewick Brook. Bradstreet, engaged in colonial government and diplomatic affairs, was often away from town, but his new homestead required, in any case, more physical labor than he or his studious young sons were prepared to perform themselves.

White and indentured servants (men and women who sold their time for a certain number of years in return for passage to America) were scarce outside the larger population areas, and indigenous people captured in the Indian Wars were considered too unskilled and recalcitrant for comfortable cohabitation with the colonists. Negro slavery was seen as the easiest solution to this labor shortage, and most New England Puritans, believing they had been chosen by God to fulfill a special role in human history, had little trouble squaring the practice of enslavement with their Christian beliefs. Some considered those they enslaved less than human, having no souls. Others, such as Cotton Mather (two generations younger than the Bradstreets) believed all men were created by God and it was thus a kindness to baptize them and bring them to the church.

We don’t know what Simon or Anne Bradstreet believed. The tone of Anne’s poems is frequently sarcastic about Puritan society’s assumptions about women’s and wives’ roles, but mostly silent on bondage, except for a passage she wrote in 1643 in praise of her mother. “To servants [her mother was] wisely awful but yet kind, and as they did so they reward did find.”3

We know the names of only a few people, besides Jack, who were employed or enslaved by the Bradstreets. In 1666, as recounted in one of Anne’s most famous poems, Verses Upon the Burning of Our House, the Bradstreets’ Andover home was consumed by a fire reportedly caused by “carelessness of the maid.” In 1696, a “mullatoe” child named Stacy, born in the Bradstreet house to parents Gallia Nota and John Stacy, was drowned at the age of ten. Jack himself was probably left with the Bradstreets’ son Dudley after Anne’s death in 1672 and Simon’s move to Salem. Upon his death in 1697, Simon Bradstreet conveyed two enslaved women, Hannah and Bilhah, to his second wife, also named Anne.4

Jack likely had considerable horticulture skill.

Apple trees, not native to America or initially well-suited to the weather and temperature extremes of the New England climate, were not easily cultivated in seventeenth-century Massachusetts. The first arriving Europeans had found only a few varieties of wild crabapples, alongside the native fruits red haw, blueberries, and huckleberries, and seeds and seedlings brought by the Plymouth settlers failed to thrive. Apple seeds are also notoriously variable (in botanists’ terms heterozygous); apple seedlings or pippins often bear only a glancing resemblance to the parent tree. Better results are obtained by grafting, but grafted stock is expensive and not practical for large tracts of raw land, such that found in Andover.

New England’s first orchard was cultivated by Rev. William Blackstone or Blaxton, a member of the failed 1623 Gorges expedition, who lived alone on the Shawmut peninsula on the site that’s now Boston Common. When the ship Arbella, carrying both Governor John Winthrop and the Bradstreets, landed in present-day Charlestown in June 1630, they found Blackstone with an established farm and orchard of “yellow sweeting” apples. Blackstone invited the newcomers, suffering from water-born illness, over to his side of the Charles River, but soon clashed with them, refused to join their church, and within a few years, moved to Rhode Island where his apple became known as the “Rhode Island Greening.” Like the equally famous “Roxbury Russet,” developed in the mid-1830s by Joseph Warren (father of the Revolutionary War patriot), the sweetings were a firm, coarse-textured, greyish-green apple with yellow-green flesh, well suited for cider or juice.5

It seems likely that Jack, saving seeds from an apple core, succeeded in growing something resembling one of these varieties. Many of Andover’s other settlers soon established orchards of their own, perhaps purchasing seedlings from Boston but Jack’s original tree remained a recognized landmark for several generations. In 1734, “Jack’s apple tree” (on the plot of land sold in the meantime by the Bradstreets to the neighboring Fryes) was willed by Capt. James Frye to his negro servant Peter along with a cow, “Peter’s wife,” and four acres of land in Methuen once Frye’s wife Lydia had died.

Did Jack have descendants?

We don’t know. There may have been a family relation between Jack and Peter. In any case, an apple tree would have been a useful asset for Peter’s family, just as it was to settler families in other places and eras. Apples could be eaten fresh; baked in pies, “slumps” or “grunts;” fried with pork; or dried and preserved in many different ways. Cider was especially valuable in the colonial period both for family consumption and as barter for other goods and services.6

From these small beginnings

Andover, like many other New England colonial towns, was soon well-supplied with apple trees. A visitor in 1789 even noted the abundance as one reason for the town’s relative lack of transient crime. “There is no occasion to rob orchards, [there being] plenty of apple trees whose branches hang into the road in a manner to invite the traveler to taste.”7

More to come . . .

In the next entry of “Long Memories” I’ll share another story of a historic town tree. I love questions and comments. Do you have a favorite tree or story that you’d like me to feature? Click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

Thanks for reading!

Jane

Charlotte Helen Abbott, “Africa to Andover” printed in the Andover Townsman, March 15, 1901.

Bound for America: The Forced Migration of Africans to the New World, by James Haskins and Kathleen Benson (1999).

Anne Bradstreet, “Her Mother’s Epitaph.” 1643.

Essex County registry of births and deaths.

Nathaniel Brewster Blackstone, “Biography of the Reverend William Blackstone,” 1974

See Susan McLellan Plaisted on Early American and Native American Foodways (hearttohearthcookery.com)

cited in Sarah Loring Bailey’s “Historical Sketches of Andover,” 1880.

Such a rich, detailed piece on a tree - and a unique lens to learn New England's history. I am new to Massachusetts and look forward to more essays about her varieties and their stories. Thank you, Jane!

Hope you're planning to include the Bicentennial Elm, on the south side of the Library on the Phillips campus. Paula Trespas wrote about it in the Andover alumni Bulletin about 10 years ago.

Dick Howe