Mystery Monday: Turtle Mound, part 3

“A cautionary tale about how well-meaning researchers created a mythology"

Researcher and author James Gage ended his 2019 report on Turtle Mound with, “This is a cautionary tale about how well-meaning researchers created a mythology for an archaeology site. It has taken 80 years to undo it.”1

My two previous posts on Turtle Mound focused on the ground level earthworks and Paul Follansbee’s nursery business and rockery. For those posts and this one, I relied on Gage’s report, which can be read in full on the AVIS website.

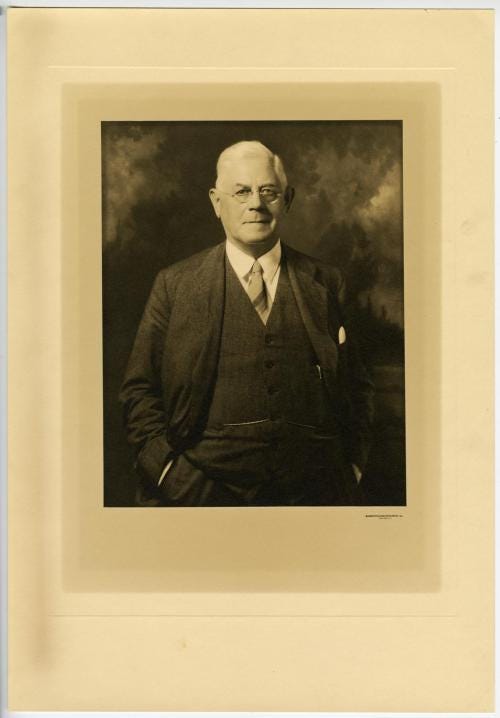

Paul B. Follansbee’s nursery business was active in Andover from the mid-1800s through at least 1910. Follansbee and his son John created the rockery between 1860 and 1880. The business and site was a tourist destination through 1919. The rockery was well-known through 1924, when a later owners of the property, French Canadian immigrants John Arnois and Armand Vohl, used a section of the rockery as a shrine to the Virgin Mary.

So how did the Follansbee nursery and rockery become “Turtle Mound” in 1939?

First, let’s dive into what was on the site at the time

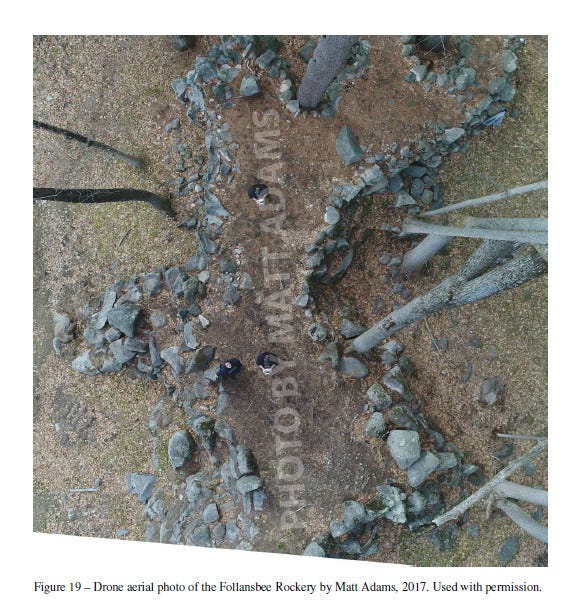

In his report, James Gage gives a detailed description of the site which includes northwest and southwest alcoves, the south and northeast grottoes, a tunnel, stone steps, sloped ground, and a small cave.

Follansbee lacked heavy moving equipment, so boulders too large to be moved were blasted apart, technology that certainly was not available in 983 AD, as would later be theorized.

“The process involved drilling a single 1 ½ inch diameter hole into the center of the boulder, filling it partially with gunpowder, a fuse, and tamping material...Examples of these blast holes can be seen throughout the mound. The large diameter deep blast drill holes seen in the boulder date to after 1800.”

The stone arch entrance of the south grotto and tunnel, were made from blocks of stone split using the plug and feather method, which dates to 1820 and later.. You can watch a short video here:

Other features of the site include “geologically interesting rocks” collected by Paul Follansbee, who was an amateur geologist in addition to other interests. Five “standing stones” are also still present on the mound.

A 1939 map includes a small building on top of the mound. The building was likely built after Paul Follansbee’s death in 1900. Four blacksmith-forged iron eye bolts that still remain were anchored to large boulders to secure the building.

William Goodwin, 1939

The story begins with William Goodwin, “an insurance executive from Hartford, CT, with a fascination for archaeology.” William Goodwin, Malcolm Pearson, and engineer Douglas Blizzard investigated the site in 1939. Correspondence between Goodwin and Pearson was found in the files of the New England Antiquities Research Association (NEARA).

William Goodwin and Malcolm Pearson were searching for evidence of “Vinland,” the area of North America explored by Leif Erickson in 1000 CE, by comparing New England geography with Norse legends.2

However, before Goodwin had completed his research into possible Viking presence in New England, Pearson “convinced him that another group was involved – the Irish.”

Sites in Upton, North Salem, and Andover were all “ceremonial centers for the vast network of Irish missionaries he envisioned across New England.”

“He envisioned the missionaries traveling up the Merrimack River, establishing outposts along the way…Beginning in 1939, Goodwin, Douglas Blizzard, and Malcolm Pearson explored the Merrimack River corridor looking for potential archaeological sites which fit Goodwin’s hypothesis. The Andover area, which is near the Merrimack River, attracted their attention due to reports of Native American earthworks. Exactly how Goodwin and Pearson stumbled upon the ‘turtle mound’ was not recorded but it quickly became the center of their focus.”

All evidence of 19th century technology and work were dismissed as past owners removing material and robbing the site. In his letter, Goodwin “mentions the ‘French-Canadian’ and the ‘nurseryman’ as past owners. Even though they talked with neighbors, local people who knew Follansbee, and other local experts, they disregarded the information.

“The bulk of Goodwin’s report is a series of arguments trying to discredit the local oral history of the site….No effort was made to check the local business directories to verify or refute the presence of the nursery.”

There’s an amusing line in a letter Goodwin wrote to Pearson in 1939, in which he referred to a meeting with a Mr. Parsons and that “Johnson and Byers” were among the “men who have controverted us. Byers is the worst and I have him on record for the proper time.” According to the 1939 Andover Street Directory, Douglas Byers was an anthropologist living at 26 Phillips Street in Andover. You can read more about Byers on the Peabody Museum of Archaeology website.

In 1945, Goodwin published an article in the Archaeological Society Bulletin, where he made his case for “The Ruins of Great Ireland in New England.” He referred to the site as an “effigy mound” and coined the phrase “Turtle Mound.”

According to Gage, Goodwin was the only one who saw the shape of a turtle in the mound. In his engineering report, Douglas Blizzard didn’t mention an effigy or a turtle shape.

“Even today, it is difficult to conceive how Goodwin came to such as conclusion. Notwithstanding this difficulty, the name became associated with the structure.”

Frank Glynn, 1951

In 1951, amateur archaeologist Frank Glynn excavated eight locations on the site. His report, The Effigy Mound” A Covered Cairn Burial Site, was published posthumously in 1969. In it, Glynn reported finding evidence of a Western European Neolithic cairn burial site, basing his theory on his interpretation of soil layers, evidence of an intense fire, cobbles arranged in an oval, and other features.

Glynn, too, dismissed the local history of the site and interpreted the mound as a “cairn covering a human burial.” He did not, however, make a cultural identification for who would have built the cairn, although he did refer to archaeologist Ripley Bullen’s work at other local sites.

Like Goodwin, Glynn interpreted the modern stone work as evidence of later owners robbing the site, rather than from its 19th century creators.

“Although it is clear from the report Glynn was not familiar with 19th century stone quarry methods.” Nor could he have been familiar with later 20th century research into soil formation dynamics, so his interpretation of the soil layers “of the mound sounds logical, [but] it is not correct. The mound’s construction can be dated to between 1860 and 1880 AD.”

The editor’s note when the report was published in 1969 was

“So astonishing were the implications of his findings, suggesting as they did a Western European Neolithic burial site, that they found no acceptance in the published archaeological literature.”

The “Turtle Mound” legend grew

In what we might call today a case of confirmation bias, William Goodwin searched for, interpreted, and dismissed evidence to support his theory of Irish missionaries in New England in 1000 AD. He coined the name “Turtle Mound” to support this claim.

The story was the perpetuated by Frank Glynn who also disregarded local history about the site without seeking evidence to confirm or refute the existence of the nursery and rockery.

Today the story of Paul B. Follansbee’s Haggett’s Pond Nurseries and his destination arboretum, museum, and rockery is being shared by AVIS, the owner of the property, researcher and author James Gage, NEARA, the History Center, and local newspapers, including the Lawrence Eagle Tribune.

So I’ll end as I started this story with James Gage’s conclusion:

The legend of Turtle Mound is a “cautionary tale about how well-meaning researchers created a mythology for an archaeology site. It has taken 80 years to undo it.”

Thanks for reading!

~Elaine

If you haven’t yet, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to History Buzz. Your paid subscription supports the research and writing that makes History Buzz possible. Thank you!

Quotes throughout this post are from James Gage, A History of the Paul B. Follansbee Rockery (a/k/a “Turtle Mound”), Andover, Massachusetts, 2019

Other resources include:

Connecticut Historical Society website

Naugatuck News, from Newspapers.com via Ancestry.com

David Goudsward, Ancient Stone Sites of New England and the Debate Over Early European Exploration, 2018, p111