Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

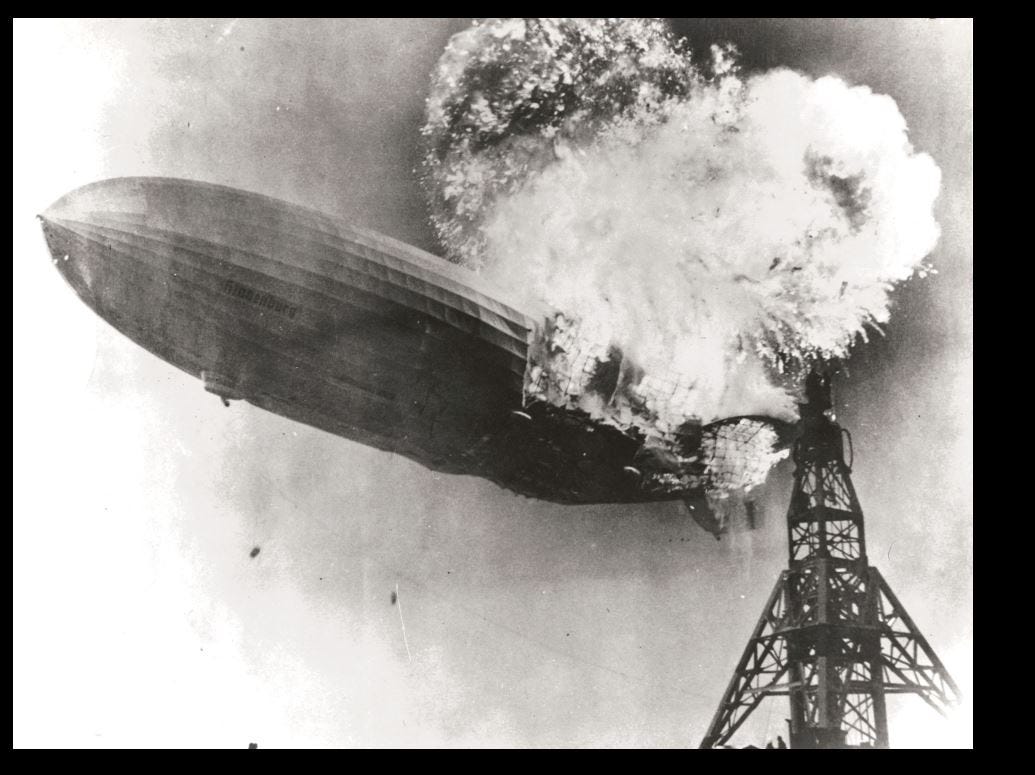

We all know the story of the Hindenburg's last flight that ended on May 6, 1937.

It was an uneventful voyage that started in Frankfurt, Germany on May 3. The "sailing" was smooth until the zeppelin was subjected to headwinds near Boston and thunderstorms in the New York metro area. A late morning/ early afternoon arrival in Lakehurst, New Jersey was delayed, and delayed, and delayed.

The commonly-accepted cause of the Hindenburg crash is that hydrogen used to keep the zeppelin airborne ignited when it came into contact with static electricity in the outside air. Thunderstorms were present in the area.

The crew was releasing hydrogen to reduce buoyancy and level the zeppelin in preparation for landing. Six crew members were sent forward to put more weight in the bow. Remember that the hydrogen was used to keep the Hindenburg airborne. The engines were powered by something else, probably a concoction called blaugas.

Hydrogen was also leaking from one of the containment cells. A member of the ground crew, the "landing party", noticed a fluttering in the outer cover of the ship near cell number 5. To this day, nobody knows what caused the leak.

The first flames were spotted at 7:25pm and the airship crashed to the ground 1 minute later. Out of the 97 people on board the Hindenburg, 62 survived. One member of the ground crew was killed as well. As staggering as those numbers seem to us, the survival rate was considered miraculous.

Marie Kleemann, one of the 36 surviving passengers, was headed to Andover. Her daughter and son-in-law, John and Katharine Bolten, lived on South Main Street. They were described as "frequent zepp passengers". In a subsequent article, the Andover Townsman mentioned that John's company, Bolta Rubber, manufactured food trays that were used aboard the Hindenburg. Furthermore, Wilhelm Von Meister, zeppelin representative in the United States, was Marie's neighbor in Germany.

John was in Newark, New Jersey, awaiting Marie's arrival. She was to take a plane from Lakehurst after disembarking the Hindenburg. Katharine, recovering at home from surgery, heard the news flash on the radio and feared that her mother had been killed. Von Meister telephoned the Bolten estate around midnight to say that Marie was okay. John was not reunited with his mother-in-law until four in the morning. Marie had been taken to a clinic for a check-up.

Five minutes before the crash, Marie went upstairs to the third deck to watch the landing through an observation window. That decision saved her life. A stewardess who was working in her stateroom perished in the crash.

Marie was watching the landing when she heard a “great big detonation.” “Great big men, bigger than John, were tossed about, hurled against me, thrown flat onto the floor.” Marie heard a second explosion soon afterward.

"A steward saved me." Marie recounted. "The decks below me were demolished when they hit the ground and everybody down there was killed." The steward led her to safety through what she called "a split in the shell". He went back inside the burning zeppelin to look for other survivors. Marie did not catch his name. Patrick Russell, who researches the passengers and crew, suggests that the steward’s name was Fritz Deeg.

Reporters from several newspapers interviewed Marie here in Andover. Her physical injuries were minor. She had a few bruises and her hair was burnt in a few places. A flashbulb startled her, prompting the Townsman writer to suggest that she was reliving the explosions.

The Daily Boston Globe shared a little more. Maybe the Townsman was wary of causing embarrassment to a local family. “She closed her eyes as if to shut out forever the sight of the blinding ‘Erschutterung’ explosion and to erase the vision of panic and horror and death that changed the impending landing to tragedy.” John had intended to fly back from New Jersey. Marie could not bear another flight, so they took a train to Boston. Visibly tired at the end of her interview, Marie went to bed early on the night of May 7.

As the Hindenburg passed over Boston on its way to Lakehurst, Captain Ernst Lehmann said to Marie "Sorry I can't let you down here."

Marie survived the horrors of World War II in Germany and spent her final years in the United States, along with her husband Friedrich. Marie became a United States citizen in 1954. She, Friedrich, and several other members of the family are buried in Spring Grove cemetery. Patrick Russell’s blog, Faces of the Hindenburg, features more about Marie’s life both before and after her zeppelin trip.

A couple of years ago, I read Empires of the Sky: Zeppelins, Airplanes, and Two Men's Epic Duel to Rule the World. Author Alexander Rose chronicles the development of the airship and the competition between airships and airplanes for dominance of the skies. Juan Trippe, of Pan Am fame, flirted with the idea of using airships. I knew of Marie's story by then and looked for her by name. She was not mentioned. If you want to learn more about the development of airships, Empires of the Sky is a great read.

Thanks for reading. Please like, share, and leave comments. We love to hear from History Buzz readers!

~Doug

Further Reading:

Airships.net. The Hindenburg Disaster. Accessed April 8, 2023.

“Andover Woman’s Mother Tells of Hindenburg Explosion.” Andover Townsman, May 14, 1937. Also available via microfilm at Memorial Hall Library

“Mother Safe in Zepp Disaster.” Andover Townsman, May 7, 1937. Also available via microfilm at Memorial Hall Library

Ask Smithsonian: What Really Felled the Hindenburg? Accessed April 8, 2023

Faces of the Hindenburg. Accessed April 27, 2023

"Hindenburg". Encyclopedia Britannica, 25 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hindenburg. Accessed 19 April 2023.

Wikipedia. Hindenburg Disaster. Accessed April 24, 2023

Woman Cannot Recall Escape. Daily Boston Globe. May 8, 1937. Accessed electronically via the Boston Public Library.

I just now found your article, and it's very nicely done!

I hadn't previously known that Willy von Meister knew the Kleemann family, though I did note awhile back in researching von Meister that his parents lived in Homburg at the time Willy was born in 1903. His father was "Landrat" for the region (basically the government administrator for a given district) so I can certainly see how he and the Kleemanns would have known one another. By 1937, however, Willy von Meister was a US citizen living and working in New York, but as VP of the American Zeppelin Transport Company, he would certainly have had early access to survivor lists when the Hindenburg crashed, so it doesn't surprise me that he'd have called the Bolten home to let them know that Marie was safe.

If I might offer one minor technical correction, the Hindenburg's engines were Daimler-Benz diesels and as such ran on heavy fuel oil and not on blaugas. The Zeppelin Company did use blaugas for the engines of the Graf Zeppelin, their previous airship, in an effort to limit the amount of hydrogen they needed to valve in flight. Blaugas weighed slightly more than air, so burning it as fuel didn't lighten the airship appreciably on longer flights. But this also made it more of a fire danger than hydrogen, since any loose blaugas would tend to settle along the keel rather than rising up to be vented topside as the much lighter hydrogen did. Hence, the decision to run the Hindenburg on diesel engines instead.

But again, that's just a minor factual issue. I quite enjoyed your article. (And thanks for crediting my Faces of the Hindenburg blog article on Frau Kleemann.)

Best,

Patrick Russell