Miscellany Mondays: Pigeon, it's what's for dinner

Today, first-time History Buzz contributor Doug Cooper takes a deep dive into an architectural feature of the Blanchard barn, pigeon-fancying, dining, and much more.

Today, we’re happy to introduce new History Buzz contributor Doug Cooper. If you enjoy this post, please consider becoming a subscriber to have History Buzz delivered to your inbox every week!

The barn at the Blanchard House contains many interesting features and architectural elements.

Inside the barn in the hayloft, is a long box attached to the exterior wall. Look closely and you’ll see a series of arched holes. The holes once opened to the outside, where you would have seen the series of arched holes to the left of the barn doors under the eaves of the roof.

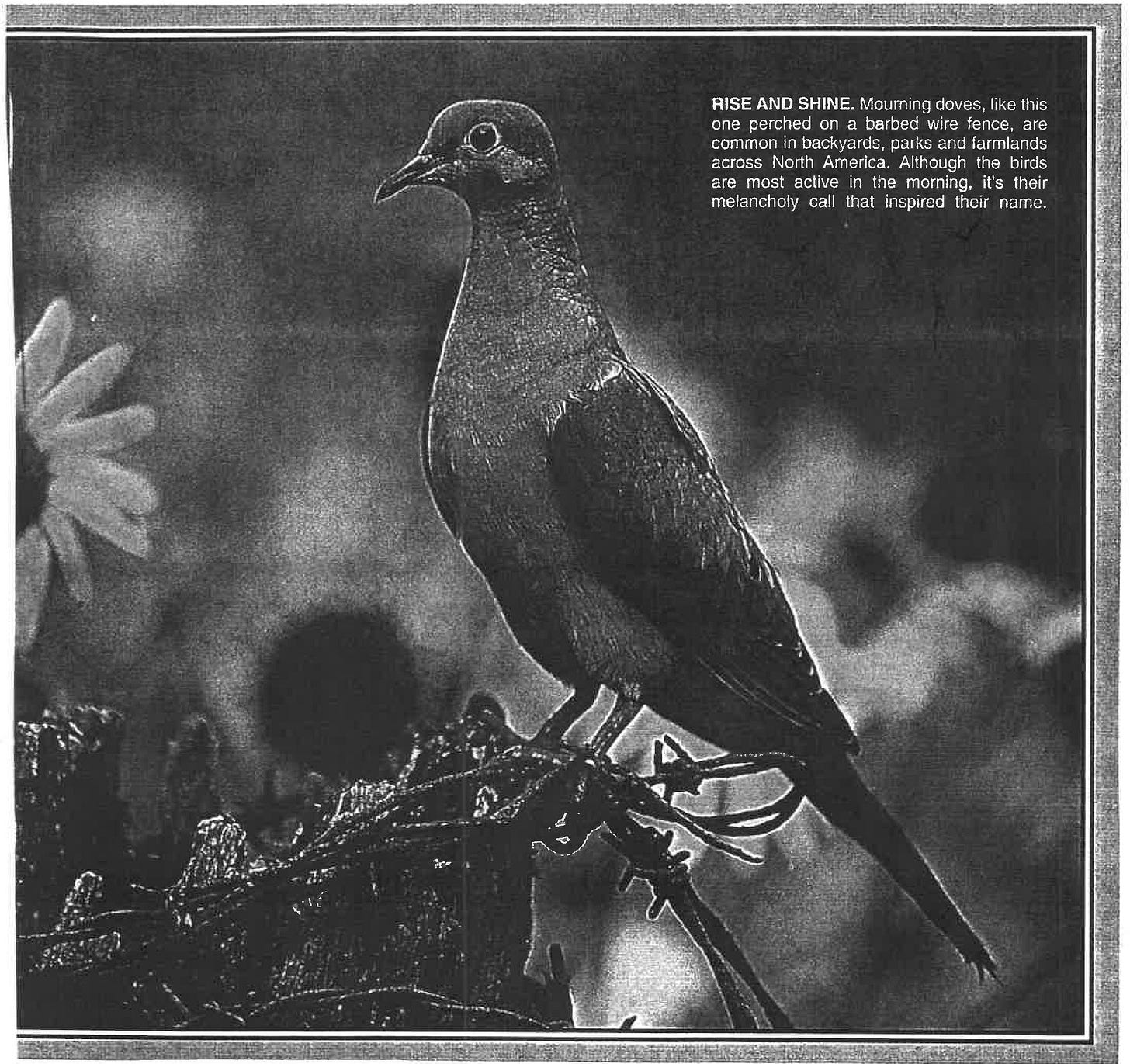

The holes led to a dovecote, which is a structure used for breeding and housing pigeons. Dovecotes function more like a bird house than a cage for someone’s parakeets. Birds that enter are free to leave and seek food wherever they may find it. How something built for pigeons came to be called a dovecote is anybody’s guess. One source that I consulted suggests that “pigeon-house” was preferred here in America.

One of the unsolved mysteries at the Andover Center for History and Culture is who installed the dovecote and why. Was it Amos Blanchard himself or was it Edward Taylor, who bought the house from the Blanchard family? Did either of them pursue pigeon-fancying, meaning that they bred pigeons as a hobby? Or, were the birds destined for the dining table? I, perhaps foolishly, decided to take a crack at solving the mystery.

Humans have been keeping domesticated pigeons for five thousand years. Most people have heard about pigeons being used to carry messages. Pigeons have also been bred for food and for human entertainment. Distinct breeds created by pigeon-fanciers include laughers (because of their chuckle-like song), tumblers (that tumble in mid-air), and parlour rollers (that somersault on the ground but do not fly). Frill-backs, according to Amelia Soth in an article for JSTOR daily,1 look like victims of a bad perm. I am thinking back on my visits to the Topsfield Fair and the many unique looking fowl on display.

Breeding visually-appealing pigeons was all the rage among European nobility. In some places, the nobility had the exclusive right to construct dovecotes. Hungry pigeons could leave their exclusive dovecote and help themselves to the grain planted by nearby peasants. Even the birds destined for the aristocratic table were fattened up with the peasants’ grain. The common people of France were so angry that, in 1789, they would march into their lords’ homes and demand wine, cheese, and the heads of the pigeons. The Victorian era was the golden age of pigeon-fancying. It can also be seen as the end of the hobby’s exclusivity.

My research yielded very little about nineteenth century pigeon fancy-ing here in the United States, which leads me to believe that it was more popular in Europe. Meanwhile, an article entitled American Restaurants and Cuisine in the Mid—Nineteenth Century2 contains several dozen recipes for pigeon. I suppose that one could raise and train a parlour roller and then eat it, but why go through all the trouble. Unless, of course, the person was near starvation.

I don't know who it was in the barn with the pigeons! I have not found any notation about buying bird seed, any mention of the dovecote's construction, no mention of a particularly pretty pigeon. But I have my suspicions. And they lead to the dining table.

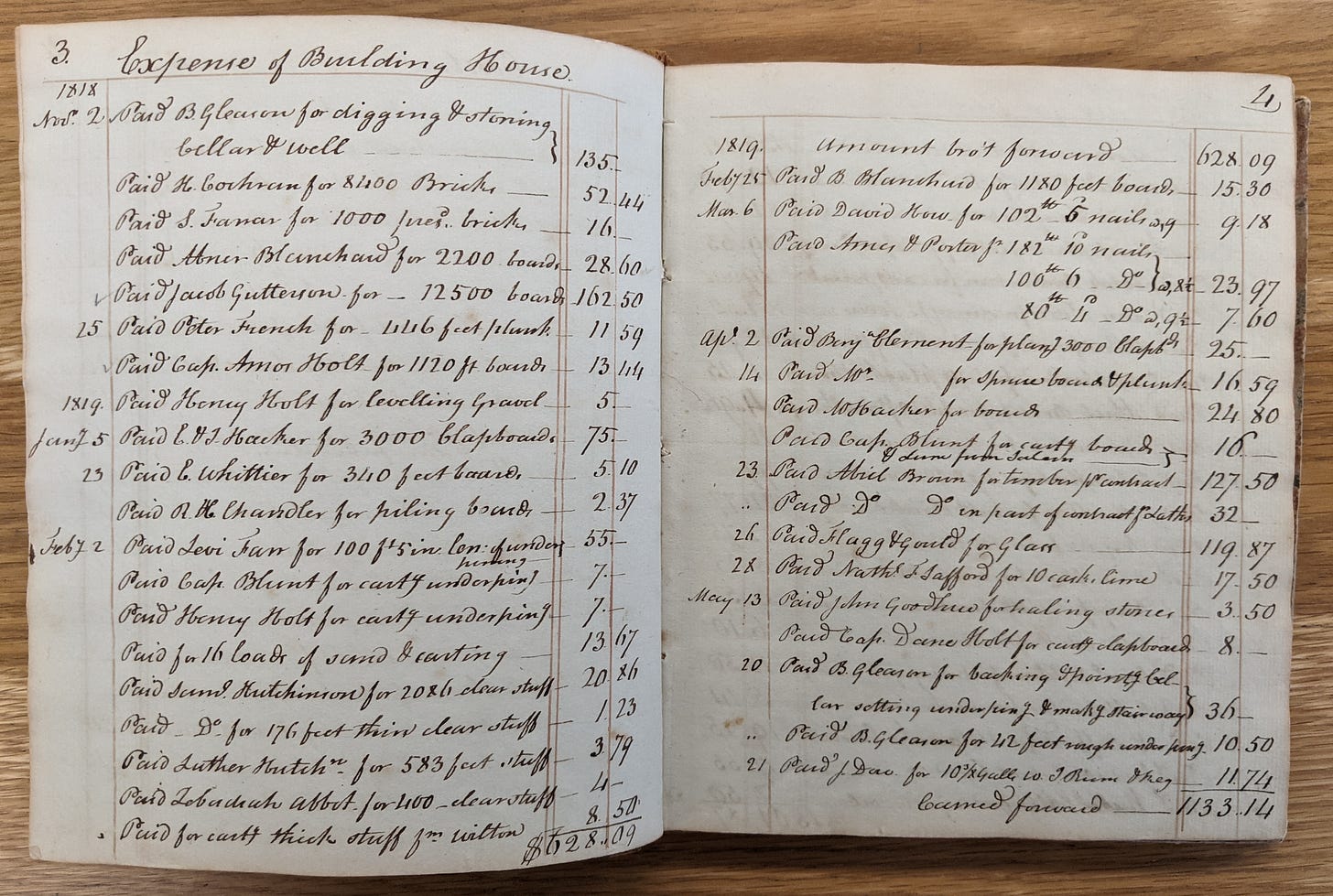

My first stop was a ledger that Amos Blanchard used to chronicle the construction of the barn and house. It’s a treasure trove of meticulous notes regarding the cost for materials, their transport, and even the hours of individual workers.

I was hoping for a tell-tale notation about bird seed. I was so new to the study of pigeon keeping that I thought that keepers provided the food. They did not, as the French farmers would tell us.

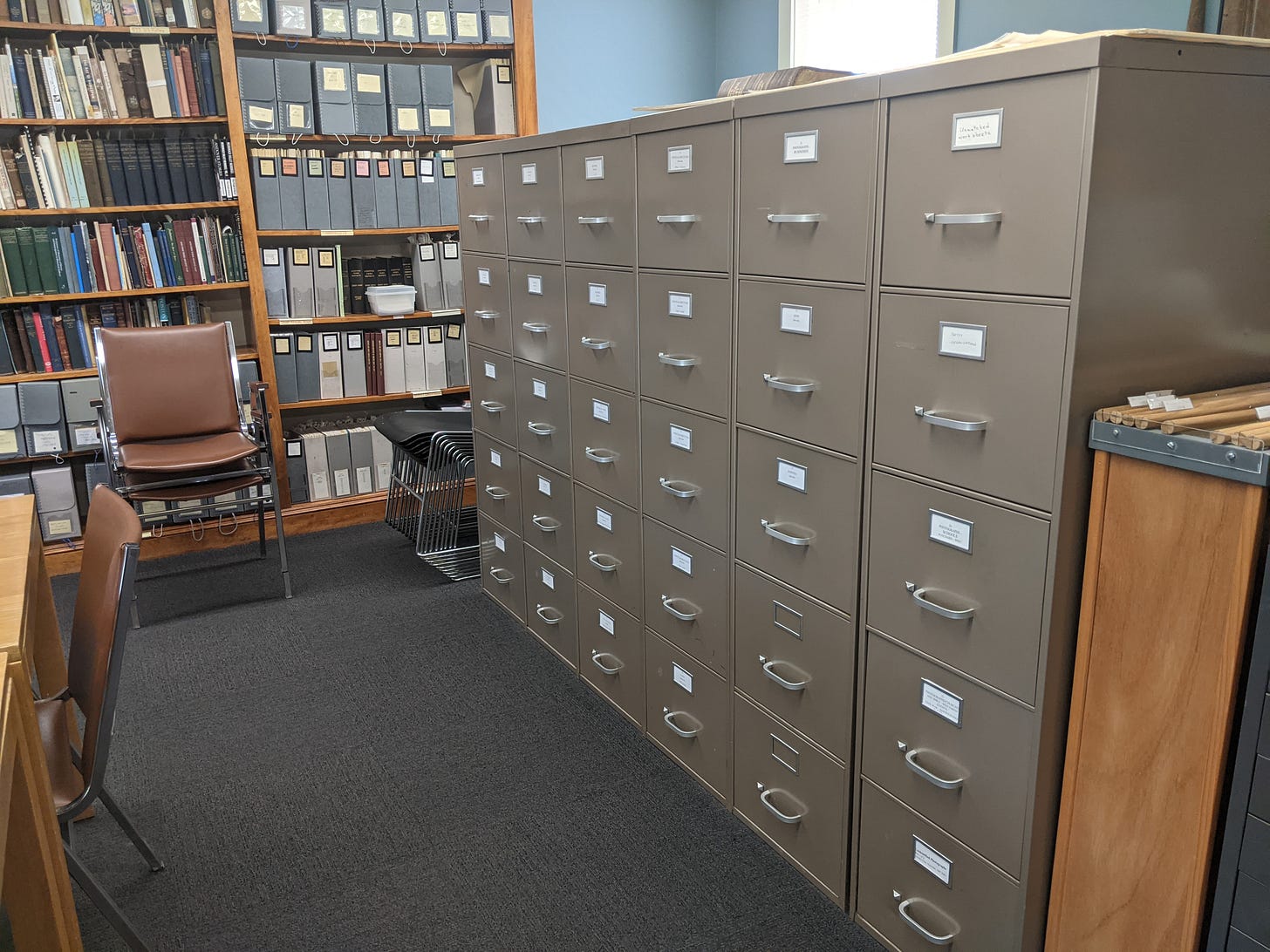

The vertical files at the Andover Center for History and Culture are one of my favorite places to go as a researcher. There's a wealth of information in there that is diligently arranged by category and sub-category.

My first discovery was a historic structure report on the barn that was compiled by Arthur Bennett. That report, in turn, refers to a document written by Thomas Hubka that discusses the Blanchard Barn as an artifact. Neither of these documents can conclusively date the dovecote. It dates from the mid nineteenth century, possibly earlier, meaning that either Blanchard or Taylor could have installed it. Both made alterations and additions to the barn during their ownership of the property. Blanchard made changes merely a year after construction was completed.

Although the vertical files are neatly organized by category, the documents contained within each file are not always well arranged. It’s a grab bag. When I flipped past the historic structure report, I found a dove staring at me. A photocopied picture of a dove, but a dove just the same. ‘Well, this is promising’, I thought to myself. The dove picture was stapled to other images and a few pages of handwritten notes. Preparation for a museum talk, perhaps? Or the original newsletter article about the dovecote? I stumbled on some of the same pictures in my later research. None of the images or notes helped me.

Character and reputational evidence are strictly controlled in court proceedings but, rightly or wrongly, are used to rank people in many other parts of life. In Blanchard’s case, we have very little to go on. Surely he wrote diaries and letters, but none have survived.

Blanchard was neither very wealthy, nor was he a farmer. He was active in South Church, held different positions at the Andover Bank, was treasurer of Phillips Academy, and served on the board of the Merrimack Mutual Fire Insurance Company. Although the Blanchards lived in town and had a degree of prosperity, they maintained cows, chickens, fruit trees, and a garden. It would be in keeping for them to raise pigeons for food.

Edward Taylor’s career was markedly similar. He worked at Marland Manufacturing Company, the Andover Bank, and later became treasurer of the Andover Theological seminary. Taylor served as Deacon at South Church for many years, and was placed in many positions of trust in the town of Andover.

My newfound knowledge about pigeon keeping in Europe made me wonder if men like Amos Blanchard, or Edward Taylor, would want to emulate European aristocrats. Since the United States was still less than a century old, they may have identified with the French peasants more so than the nobility.

Or maybe Blanchard and Taylor believed that pigeon fancying was too plebeian. As I alluded to earlier, pigeon-fancying worked its way down the social ladder during their lifetimes. Charles Darwin’s scientific efforts prompted him to keep pigeons and he did so with disdain. Darwin complained:

I am hand & glove with all sorts of Fanciers, Spital-field weavers & odd specimens of the human species, who fancy pigeons.

I am not accusing Blanchard or Taylor of being snobbish, but maybe they were status-conscious and upwardly mobile. They wanted people to think highly of them. As leaders in educational institutions and churches, it was expected of them. Eating pigeons would have been permissible. Training them and cooing at them, pun intended, would not.

One obituary of Edward Taylor states that he exemplified the Puritan and Pilgrim traits of character, both moral and spiritual. It does not mention how much he enjoyed tending to his pigeons. Would a person so closely allied with the pilgrims associate with either European aristocrats or ‘odd specimens of the human species?’ Probably not.

Maybe a new discovery will be made, or a manuscript will be acquired, that will change my mind. Unfortunately for the pigeons in the Blanchard Barn, they were probably destined for the dinner table. (Illustration 3)

Thank you for reading! As always, please comment, like, and share this article. It all helps grow History Buzz. Your paid subscription helps support the research and writing that makes History Buzz possible. Thank you!

P.S. Thank you, Doug, and welcome to History Buzz!

As I mentioned in a previous post about results from our reader survey, we’ll be trimming back to 1 to 2 stories a week. What’s It Wednesdays will be taking this week off. Marilyn will be back with her next What’s It Wednesdays on May 11. In the meantime, look for Andover Bewitched and more Miscellany Mondays!

Until then,

~Elaine

Nice article Doug. I wish the holes would show from the exterior too!

I really enjoyed this article. I am an artist and I have a fifth floor studio in Lowell with a tremendous amount of pigeon activity out my window where I get a close up, “birds eye view” of the growth stages of these fascinating birds. I also did an oil painting on location from across the street in 2015 that matches the vantage point of the photo of the barn and house.