South of Ballardvale is a roughly rectangular spit of land belonging to Andover, bounded by the Shawsheen River, Tewksbury, and Wilmington. A triangle-shaped railroad junction known as Lowell Junction characterizes the area.

From Indigenous people to industry, its history extends beyond an intersection.

First off, we can credit the distinctive boundary of Lowell Junction to a mistake.

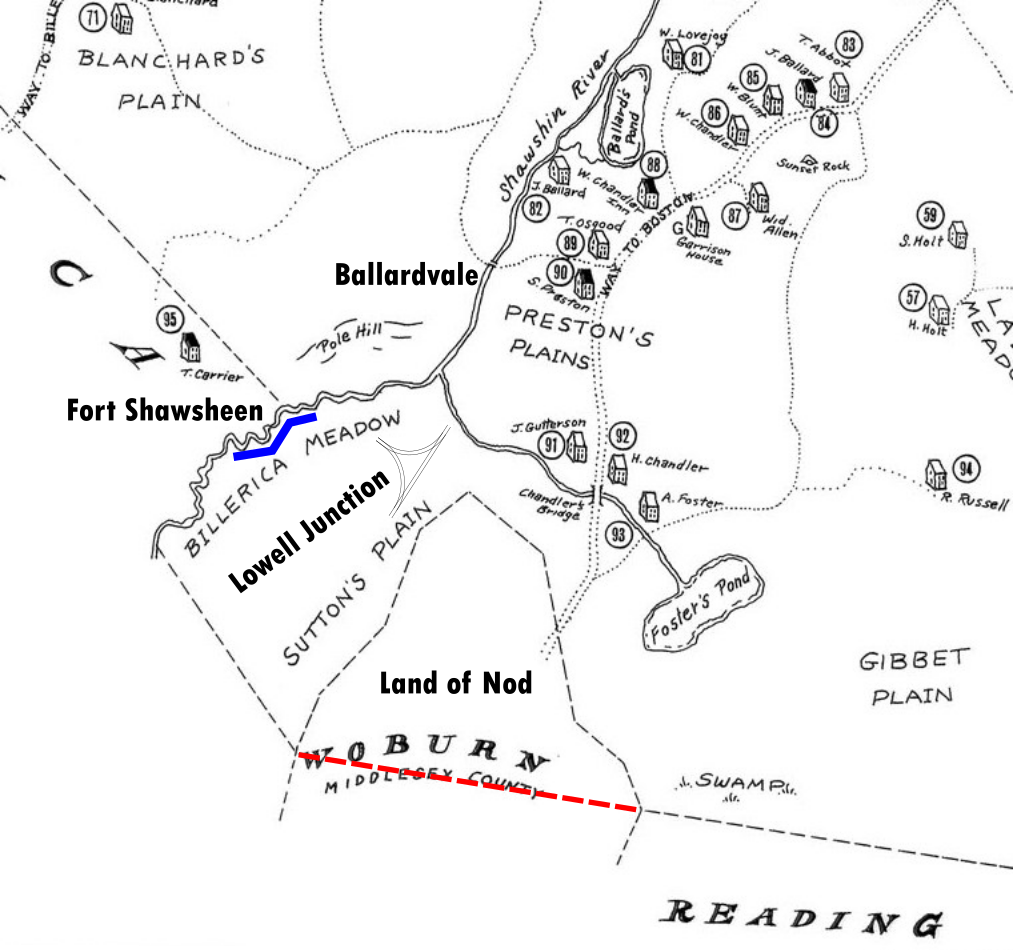

At Andover's incorporation in 1646, a straight, logical line may have served as the border between Andover and Reading. It appears as a black dash on a 1683 survey. I drew the same line in red on a map showing what Andover looked like in 1692.

In 1650, Charlestown and Woburn sought to buy land within each other’s municipalities. On July 29, the towns agreed that Woburn would exchange 3,000 acres of its remote northern land for 500 acres of Charlestown’s land further south.1

The 3,000-acre northern tract earned the name “Land of Nod,” after the place east of Eden where Cain lived in exile according to the Bible (Genesis 4:16). “Nod” means “wanderer” in Hebrew,2 but the people of Woburn referred to the remoteness of their land and its great distance from any church.3

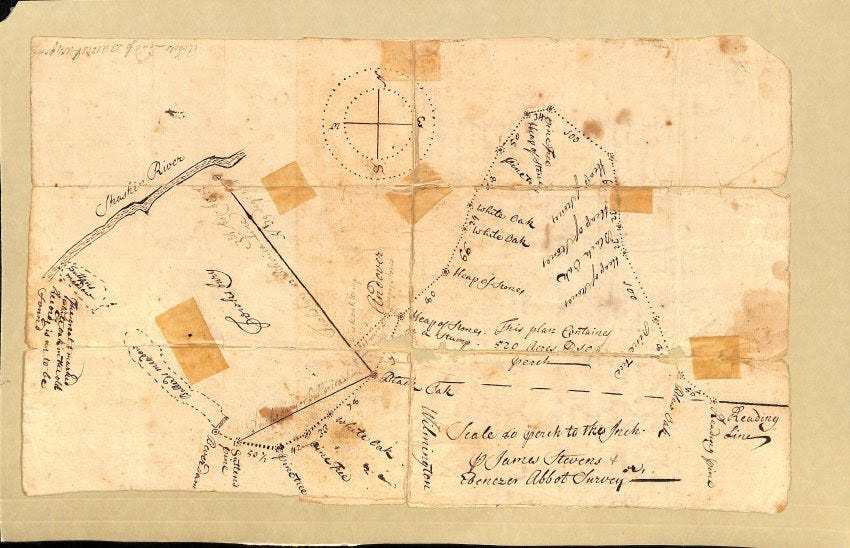

The town of Woburn hired a surveyor in 1671 to identify the 3,000 acres they would turn over to investors in Charlestown. Seventeenth-century surveying was shoddy at best, and the surveyor carved 3,000 acres out of Reading and Andover instead of Woburn.

For the next 60 years Andover, Woburn, and Charlestown disputed over ownership of the Nod. Finally, in 1734, not long after the establishment of Wilmington, Andover relinquished its claim.

The Land of Nod was not the only Lowell Junction boundary subject to heated dispute. To the west, Andover fought off land claims from Billerica and vice versa to the point where residents “could not tell whether wee [sic] have any bounds or not.”4

In the colonial era, deeds referred to Andover land between the Shawsheen River and the Nod as "Billerica Meadow" and "Sutton’s Plain."5 For a long time a tree named “Sutten’s [sic] pine” marked the corner of Andover, Billerica, and Wilmington.6

Before European settlement, the Penacook called the area home. A site known as Fort Shawsheen reveals embankments used for defense against enemies traveling the river or advancing from the north. Archaeologists found chips and flakes of chert and argillite, suggesting the production of stone tools or weapons.7 A solid blue line marks the embankment of Fort Shawsheen on the 1692 map.

The Boston and Maine Railroad cut through Sutton’s Plain in the 1830s, but it remained remote and ignored by Ballardvale after American independence. One person called it home in the 1850s: a man by the name of W. Burtt. He lived on River Street near the Wilmington border.8

In 1874, everything changed. A monopoly on Lowell rail service expired and Boston and Maine built their own branch line connecting Lowell to Boston,9 creating Lowell Junction and fueling a new industrial center. The creative name for the new line was the Lowell and Andover Railroad.

Unlike Ballardvale, Lowell Junction factories enjoyed independence from the river for power, and instead relied on its proximity to the railroad to transport materials and goods efficiently.

One of the junction’s first businesses was the Ballardvale Lithia Springs Water Company. Lithia water is mineral water with lithium salts added for supposed medicinal effects. Founded by Lawrence businessman Paul Hannigan in the 1880s, he used Lowell Junction to ship bottled water and ginger ale globally.

The Boston-based Watson-Park Chemical Company opened in 1926 manufacturing soap for textiles. At one point they were the largest consumer of formaldehyde and sulfur dioxide in New England. The company expanded its facility in the 1930s and 1940s to include an office, storage units, laboratories, and a machine shop. Reichhold Chemical Company inherited the plant in 1952.10

Further from the railroad, the Lowell Junction area retained its rural character. Businessmen from Boston owned small camps along the Shawsheen as fishing retreats in the summer. They often hired Andover resident William Doherty, son of John Doherty, a landscaper and arborist, to repair the camp cabins each spring.11

North of the junction, Frank Serio rented canoes at his house on the Shawsheen. Unlike the rest of Lowell Junction, Serio’s property was predominantly meadowland. He built a dance platform, picnic area, and other amenities to entertain the public. Open for business from 1932 to 1968, visitors dubbed his canoe shed “The Miami Boat House.”12

The 1950s was another period of great change for Lowell Junction, spurred by the rezoning of vacant land and the construction of Route 93. Factories no longer relied on the railroad and instead used the interstate highway to transport goods, a common trend throughout the country.

The Gillette Company built a plant in the 1960s and others followed suit in the following decades, developing east of Route 93.13

The land west of Route 93 had no connection to the rest of Andover and remained vacant. Its proximity to the Shawsheen however made it an important wildlife sanctuary.

George K. Sanborn, in an effort to encourage others to donate conservation land, gave 4.5 acres west of Route 93 to the Andover Village Improvement Society. AVIS added another half-acre in 1966.14 These lands, known as the Sanborn Reservation, contained part of Fort Shawsheen.

Meanwhile, Andover residents faced the negative consequences of the industry of Lowell Junction. The Reichhold Chemical Company's unlined waste ponds allowed toxic byproducts from resin production to leach into the Shawsheen River.

Reichhold was not the only polluter, but the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection required them to put in place a remediation plan from 1979 to 2012.15

Conservation efforts also protected land on the Shawsheen from further development and pollution. Purchases include Shawsheen Pines in 1968, the site of the waste ponds in 2006, Frank Serio’s land, now called Serio’s Grove, also in 2006, the Lightning Tree Reservation in 2013, and an expansion of the Sanborn Reservation in 2015.

Today these reservations provide recreational opportunities and protect historical sites and wildlife habitat.

The railroad junction is partially abandoned — local companies have little use for it — but PanAm and the MBTA still use the tracks for passenger and freight transportation. Some Lowell Junction companies are household names like Pfizer, Gillette, and Market Basket. Mixed in are smaller businesses specializing in mulch, solar power, labeling, and more.

Samuel Sewall, The History of Woburn, Middlesex County, Mass.: From the Grant of its Territory to Charlestown, in 1640, to the Year 1860. (Boston: Wiggin and Lunt, 1868), 540-543, https://archive.org/details/historyofwoburnm00sewa.

Isaac Asimov, Asimov’s Guide to the Bible: Two Volumes in One: The Old and New Testaments (New York: Avenel Books, 1981), 34, https://archive.org/details/asimovsguidetobi00asim.

Sarah Loring Bailey, Historical Sketches of Andover (Comprising the Present Towns of North Andover and Andover), Massachusetts (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1880), 62-63, https://archive.org/details/historicalsketch00bail.

Bailey, Historical Sketches of Andover, 62.

James S. Batchelder, Gratia Mahony, Rockwell Forbes, and Carl Smith, Plan of Andover in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, Essex County, 1692 (Andover, MA: Historical Societies of Andover and North Andover, 1992), http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/maps/andoframe.html.

Bailey, Historical Sketches of Andover, 62.

Warren K. Moorehead, Bulletin V: Certain Peculiar Earthworks Near Andover, Massachusetts (Andover, MA: The Andover Press, 1912), 35-37, https://archive.org/details/certainpeculiar00moor.

Henry Francis Walling and Augustus Knoller, Map of the Town of Andover, Essex County, Massachusetts (Boston: Henry F. Walling, 1852), https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:0r96fm02s.

Ronald D. Karr, The Rail Lines of Southern New England - A Handbook of Railroad History (Albany, NY: Branch Line Press, 1995)

Gail Ralston, “Andover's oldest industrial park at Lowell Junction,” Andover Townsman, May 10, 2018, https://www.andovertownsman.com/news/lifestyles/andovers-oldest-industrial-park-at-lowell-junction/article_3272fcde-83a1-5535-b2c2-707f0f60cf46.html.

James D. Doherty, Andover As I Remember It (Andover, MA: James D. Doherty, 1992), http://www.pa59ers.com/library/Doherty/Andover4.html.

Gail Ralston, “Andover Stories: Serio's Grove provided entertainment on the river,” Andover Townsman, October 7, 2010, https://www.andovertownsman.com/news/local_news/andover-stories-serios-grove-provided-entertainment-on-the-river/article_29dcd1e2-0abb-527e-b33d-a605ec57fe37.html.

Doherty, Andover As I Remember It.

Juliet Haines Mofford, AVIS: A History in Conservation (Andover, MA: Andover Village Improvement Society, 1980), 101.

Ralston, “Andover's oldest industrial park at Lowell Junction.”

Lowell Junction was also the terminus for the Eastern RR that ran from Salem through Peabody, North Reading and Wilmington to the Junction. This RR was built in 1848 and was taken over by the B&M in 1870. The last passenger train ran in 1933 and the last freight train was in 1939. The rails were later removed for the war effort...My grandfather (1881-1973) said there was once a large engine turnstile at the junction..

I am the Grandson of William Doherty, the carpenter mentioned in the story. My Grandfather built a number of homes in Andover in the 1920-40s mostly in the Harding Street and Hartigan Court areas. He also did carpentry repairs/upgrades all over Andover. He died I believe in 1948, always the strong, silent type and much respected by the citizens of Andover. The Doherty School is named after his son William, who was a member of the Andover School Committee for 39 years, at the time of his death then a state record.