Long Memories: A History of Andover in Ten (or so) Trees: the battles against caterpillars

Protecting trees from the ravages of destructive moth larvae has been a town concern for more than one hundred years.

In Andover’s long history, there can’t have been many people who had as deep a reverence for trees as Alice Buck (1842-1907).

Small in stature but forceful in temperament, this unmarried lady was a graduate of Abbot Academy, a Sunday School teacher and chairwoman of the November Club’s literary department when, at the age of fifty-four, she led the townspeople’s fight to save the locally beloved glacial esker Indian Ridge and its surrounding woodland. Working with a small committee of women, she orchestrated a shrewd public relations campaign to raise the necessary funds for the property’s purchase. When the Indian Ridge Association was incorporated in 1897 to hold the land and care for the new park, Alice Buck became the organization’s first secretary. Her 1904 report to the organization’s membership reveals the emotional depth of her attachment to the reservation.

There is nothing more delightful to fond parents than to talk over the charms and prospects of their children. For the trustees of the Indian Ridge Reservation, who stand as its parents, this is a happy hour, when they not only may but must indulge in a discussion of the attractions and needs of their charges. It was six years ago last month that it came into their keeping and no child of six years has ever caused less anxiety. It has never kept any one up at night. . . 1

Miss Buck’s annual reports detail the efforts she and the other Indian Ridge trustees took, as fond parents, to protect the Reservation’s trees from fire and especially destructive moths. Beginning in 1894, the Andover Village Improvement Society (AVIS) paid a cash bounty to boys (alas, no tree-climbing girls were envisioned) to clip the nests and egg “belts” of tent caterpillars, particularly in Indian Ridge. For a prize of fifteen cents per hundred, each March through early May, children were coaxed to collect the teeming nests by the wagonload to be counted and burned by their teachers. Miss Buck frequently visited the Indian Ridge School on Cuba Street herself, taking the young students--many the children of immigrants working in Abbott Village’s Smith & Dove mills--out to the Reservation for songs, stories, botany lessons, and more caterpillar destruction.

As she had with the trees, Alice Buck in 1904 described the insect pests affecting her “children” in particularly human terms. But her language in this case sounds, to modern ears, disturbingly anti-immigrant and even racially coded.

[These are] dangers for our [trees]; enemies who live on year after year; squatters who pay no taxes, who make no sign in winter but when the sap begins to mount in the spring show their little black cabins among the young trees and bushes. They raise large families, and crowd together by the hundreds, only pushing each other out-of-doors to find food. Great troubles call for heroic actions and nineteen scholars from the Indian Ridge school made two attacks on the marauders and destroyed 137 dozen homes; reckoning at the rate of one hundred in each house, this amounts to the death of 164,400 ravagers.

Immigration was, as it is now, a hot topic of discussion during the early years of the 20th century. Between 1900 and 1915, more than 15 million immigrants arrived in the United State, about equal to the number who had arrived the previous forty years combined but, unlike previous waves (like the English, Irish and Scots who came to work in Andover’s mills), came predominantly from non-English-speaking countries of southern and eastern Europe like Italy, Poland, and Russia.2 Many chose to settle in American cities—including next-door Lawrence, Massachusetts—where jobs were located but also where housing costs were high and city services were hard-pressed to keep up with the flow of newcomers. As detailed in “The Lawrence Survey,” the renowned 1912 study of that city’s living conditions, immigrant families doubled or tripled up in small apartments, crowded more people into less space, or rented a single room for what it once cost to rent an entire apartment.3

We would be wrong to make any assumptions from this one quote about Miss Buck’s attitude toward immigrants. We know she was beloved by many of Andover’s foreign-born workers and their children. But providing context to her (very likely inadvertently) hurtful language is knowledge that two of the most destructive pests threatening her beloved trees were invasive species of European origin with Massachusetts epicenters.

The nests of brown-tail moths (Euproctis chrysorrhoea) were first spotted in pear and apple trees in Somerville, Massachusetts around 1890. Within the decade, they had become widespread there and in neighboring Cambridge causing not only defoliation of trees but painful irritation to the skin, eyes and lungs of those coming into contact with the caterpillars’ barbed hairs. Investigations conducted by the Massachusetts State Board of Agriculture traced the initial introduction of the pest to a nearby florist’s nursery selling imported rose bushes from Holland and France.

The insects’ nests were found at Indian Ride in the autumn of 1906 when, in Alice Buck’s description, “Jack Frost dropped leaves from the trees.” The threat was soon seen to be, compared to the native tent caterpillars, as “the smallpox” were to “the chicken pox.”

There are many brown tail nests scattered among the white oaks of the Reservation, but no single tree is as infected as its guardian, good old Samson’s Hockey, which looks as if its twigs had been done up in curl papers. We earnestly hope the town will come to the rescue and clear the nests as Malden and Melrose have done for the park held under similar conditions for our treasury hold only $14.01.4

The insects’ spread was generally attributed to both trains and automobiles carrying moths. but another suspected source of local infestation was the large greenhouse and ornamental plant business at 33 Lowell Street in Andover.5 Interestingly, J. Harry Playdon, the greenhouse’s sole owner after 1897, was, a few years later, elected Andover’s Tree Warden and Moth Superintendent and became the town’s point man in the battle.

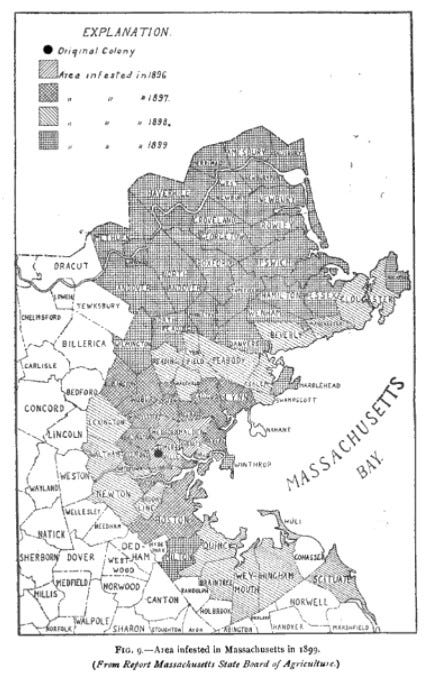

The second destructive species of moth, lymantria dispar dispar (known at the time as the European gypsy moth), was brought to North America in 1869 by amateur entomologist Etienne Léopold Trouvelot who intended to interbreed them with silk moths to strengthen the local silkworm industry. Accidentally released from their backyard cages at his home on Myrtle Street in Medford, the caterpillars were considered a local nuisance for about ten years.6 A state commission was formed to control them in 1890 but, lacking significant funding and manpower, failed to stop the pests’ spread north and west. As reported in the Andover Townsman with breathless dread, the caterpillars were identified in Woburn in 1895; the Middlesex Fells, Georgetown. Salisbury, Newburyport and Newbury by 1899; Lynnfield in 1902; and, finally, Andover in August 1905. Landowners were required by both statute and social pressure to display “eternal vigilance” in dealing with moths in their own yards but by the spring of 1910, infestation at Indian Ridge was severe enough to warrant spraying with arsenate of lead. As terrifying as this sounds from a public health standpoint, this was considered less toxic than its predecessor, Paris Green, which burned all vegetation when sprayed.

The effort proved to be futile, however. In 1916 (nine years after Alice Buck’s 1907 death) every oak tree in Indian Ridge’s twenty-three acres was cut down for lumber to save the pines. As a result of escalating control measures (aerial spraying in the 1936, DDT in 1946, and the introduction of naturally insecticidal bacteria in the 1960s), the moths became only a periodic problem through the 20th century, usually following pronounced years of drought. Many of us remember the infestation of 1981/1982, when a special town meeting was proposed to deal with the threat to the town’s trees. Ultimately, with an eye on town finances and more knowledge of the detrimental effects of chemical pesticides, the Board of Health’s Moth Subcommittee recommended “letting the moth population die out on its own.”7

In 2021, the Entomological Society of America (ESA) announced that Lymantria dispar dispar (which continues to defoliate about 700,000 acres per year in the eastern United States), will henceforth be designated the “spongy moth” in reference to the insect’s light brown, fuzzy egg masses and to avoid the unpleasant connotations now recognized in the previous common name of “gypsy moth.” As the ESA explains on its website, the word “gypsy” is considered a racial slur by many Romani people, Europe’s largest ethnic minority, who for more than five centuries have been “targets of enslavement, genocide, forced sterilization and migration, economic and social exclusion, and other manifestations of anti-Romani racism.”

The recommended change in terminology is self-evident once you think about it. The association, for more than a hundred years, of a destructive invasive species with a people persecuted and harassed into nomadism and is more than distasteful.

People are not insects, and our language should reflect that.

I love questions and comments! Click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

Thanks, as always, for reading!

Jane

History Buzz is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Indian Ridge Association minutes and logbook (Andover Center for History and Culture Collection, MSS, 620 IIb)

Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789-1945, Bureau of the Census

The Report of the Lawrence Survey, The Andover Press, 1912. https://www.uml.edu/docs/lawrencesurvey_0012_tcm18-62838.pdf

Indian Ridge Association minutes and logbook (Andover Center for History and Culture Collection, MSS, 620 IIb)

PLEASE NOTE: In the original email that went out with this post, the property was mislabeled as “31 Lowell Street.” The correct address if “33 Lowell Street.”

“The Great Gypsy Moth War: A History of the First Campaign in Massachusetts to Eradicate the Gypsy Moth, 1890-1901” by Robert J. Spear

Andover Townsman, November 1981

Gypsy moths! I remember them vividly and not fondly ... In class, Mr Sullivan (coach Sullivan) about a guy in his neighborhood who ran a wheelbarrow up and down his driveway repeatedly to squash 'em. It was probably psychology and not US history.

Fascinating post, Jane. Well done indeed!

Your story brought back warm childhood memories of the canopy of Dutch Elms that lined our street in Detroit. As a kid, it always felt like walking under the arched ceilings of a cathedral. Magnificent!

Sadly, the trees are gone now, the victims of Dutch Elm disease.

Tom