Long Memories, a history of Andover in ten (or so) trees: the Jenkins White Pine

This venerable tree is revered for the comfort and peace it offers to visitors of a little farm cemetery. It's also a stark reminder of our town's suffering before childhood vaccines were common.

In late September 1753, the three youngest children of Samuel and Rebecca Jenkins—Mary age 5, Joel age 3, and Benjamin, thirteen months—died on three consecutive days, almost certainly of the dreaded respiratory disease, diphtheria.

Samuel and Rebecca had moved to Andover about six years previously, buying a farm of several hundred acres on the direct road between Boston and Haverhill, in the southeastern or “Cape District” of Andover. Rejecting both an existing family burial plot (in what is now North Reading) and Andover’s South Parish cemetery four miles distant, Samuel and Rebecca chose to keep their children close. Mary, Joel, and Benjamin were laid to rest near an already tall White Pine tree at the edge of the family’s cultivated fields.

More than 250 years later, the children’s graves are unmarked and nearly forgotten, but the towering pine still watches over the historic Woodbridge-Jenkins cemetery on Douglass Drive. You can read Floyd Greenwood’s popular History Buzz post about the Jenkins family, the abolitionist William Jenkins, and the preservation of this cemetery here.

The Eastern White Pine (pinus strobus) has long held a place in American history. Once dominating the northern forests of North America, the species had multiple uses for both Native Americans and colonists, its typically straight and knot-fee trunks yielding durable boards easily worked and painted. The tallest specimens were reserved by the British crown as a source of ships’ masts for the Royal Navy and became such a valuable commodity that skirmishes between colonists and enforcers of the harvesting laws became common. Within a few hundred years, heavy lumbering reduced the old-growth pine forests to isolated stands and individual specimens, like the Jenkins Pine, prized for their stately and ornamental presence.

By all accounts the Jenkins family thrived in the years after the triple bereavement: adding two more sons (named Joel and Benjamin after their deceased brothers) to the older surviving children; building a new and larger house in 1765 (still standing at 8 Douglass Drive-you can read about it here); and establishing a lumber and quarry business that flourished through most of the 19th century. Between 1753 to 1878, Samuel, Rebecca, and six more of their children and grandchildren were interred in the little plot, along with six members of the neighboring Woodbridge family. The practice ended in 1882 when Jenkins descendants exhumed and moved most of their ancestors to the newly established Spring Grove Cemetery. The three oldest graves, however, were left undisturbed. They may have been unmarked and overlooked. The remains might have been judged too fragile for transport. In any case, the three little children were left behind with the Woodbridges and, of course, with the White Pine overlooking them.1

“It’s all right if you have to leave,” I imagine the tree saying. “I’ll be here.”

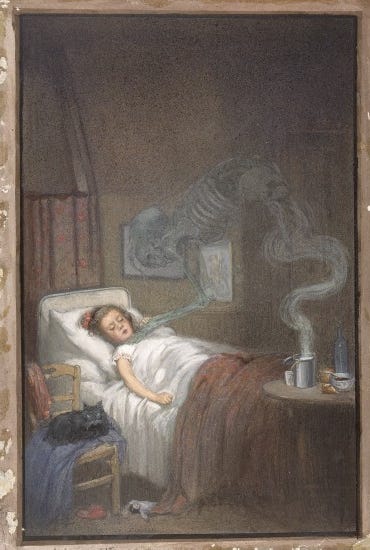

Throughout history, diphtheria has been one of the most feared of all childhood diseases with symptoms ranging from a severe sore throat to suffocation resulting from a gray membrane of dead cells completely blocking the victim’s airway. Fatality rates for this acute bacterial infection were as high as 40% in colonial Massachusetts and waves of the disease rolled through Essex and Middlesex County towns at intervals of about seven years throughout much of the 18th century. The most characteristic feature of these epidemics was the occurrence of multiple deaths per family. John and Marcy Wilson of Andover, for example, lost eight children in one week of 1738. Children of ministers and physicians are also common on the mortality lists, the disease carried home by their fathers with little understanding of the dangers of contagion.2 Perhaps the Jenkins children, having contact with travelers, were similarly exposed.

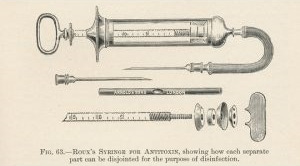

Incidence of the disease subsided around 1800 only to return later in the 19th century. Despite marked improvements in intubation (replacing dangerous tracheotomies) and antitoxins that provided several weeks of protection, mortality rates remained about 6%. Children in Andover died at a rate of one or two per week during the winter and spring months of 1899 and 1900 (when the town’s population was only 6813) and the rate was even higher in the crowded living conditions of neighboring Lawrence.

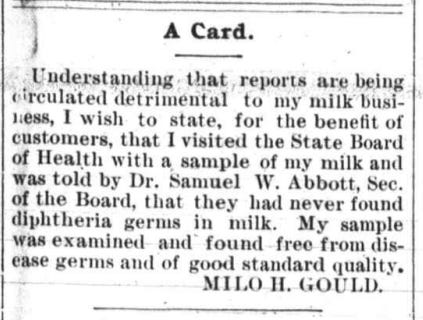

Andover’s 1899-1900 outbreak is well documented owing to the fact that suspicion for the spread of the disease fell on local milkman Milo H. Gould. Hoping for exoneration, Gould demanded an inquiry by the Massachusetts Board of Health. State investigators in March 1900 traced the source of ten infections to a teacher at the John Dove School (a K-6 facility on Bartlet Street, the current site of Doherty Middle School) in whom the disease presented as tonsilitis. Twenty-four additional cases were found to be customers of the milkman Gould, including ten Phillips Academy students. Principal Edith McLawlin was said to have brought the infection home to her invalid mother, Martha, who died in May 1899 at the age of 62. As a result, the John Dove School and several Phillips boarding houses were closed temporarily and “thoroughly disinfected with formaldehyde.” Three weeks after the state investigation, Gould’s hired man was diagnosed with the disease and taken to Boston City Hospital, presumed to be the carrier.3

Newspaper stories from this time are just as heart-wrenching as that of the Jenkins children, for whom no reporting survives. In February 1900, an unnamed child living on Fern Street in Lawrence was so restless that a doctor was forced to “wind it up in a shawl and use a tongue depressor” to examine the deadly membrane in the child’s throat.4 That same month, three-year-old Bertha Henderson, daughter of Corp. John Henderson and his wife Jemima, died at home on Mineral Street while her father was deployed, in the wake of the Spanish-American War, at Matanzas, Cuba.5 (Was this event, I wonder incidentally, part of the rationale for changing the name of Mineral Street to Cuba Street in 1904?) Most publicly lamented of all was the death of five-year-old Lowell Thayer of Chelsea, who fell sick while visiting the home of Andover Townsman editor, John N. Cole. The “bright, curly-headed” boy was a “friend of sweetness and light-heartedness,” Cole wrote, whose “littleness was only in body.” Against the fear of contagion, his body was placed the same day of his death in a “sealed casket,” Cole assured his readers, for burial in Mount Auburn Cemetery weeks later.6

The development of toxin-and-antitoxin combination serums finally succeeded in vanquishing the terrible threat. Vaccination for diphtheria was required for registration in Andover schools by 1910 and common drinking cups were abolished in favor of “water bubblers.” 7 With the development of the Tdap given to both children and adults today, the horrors of this disease have largely faded from public memory.

Only the Jenkins Pine remains to remind us.

Now nearly 400 years old (according to the town Tree Warden), the tree was damaged by a March 2017 nor’easter and appears to suffer from a form of white pine needle disease. Enduring as a focal point of the historical cemetery, it resembles, with its distinctive lateral branch, the White Pine so beloved by Henry David Thoreau:

“Great pines two or more feet in diameter branch sometimes,” Thoreau wrote in his journal in 1857, “. . . [send] out large horizontal branches where you can sit. Like great harps on which the wind makes music. There is no finer tree. The different stages of its soft glaucus foliage completely concealing the trunk and branches are separated by dark horizontal lines of shadow, the flakes of pine foliage like a pile of light fleeces.”8

More to come . . .

In the next entry of “Long Memories” I’ll share another story of a historic town tree. I love questions and comments. Click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

Thanks, as always, for reading!

Jane

History Buzz is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Andover Townsman, February 10, 1899, p. 1

Andover Townsman, February 17, 1899, p. 18

This is a fascinating post. I have heard about that farm cemetery a few times.

What a big responsibility Rebecca Jenkins gave that pine tree! I would want my darlings close, too. Thank you for a heartbreaking, haunting article about an awful childhood disease we think nothing of today (except when the kids cry getting their shots).