Long Memories, a history of Andover in ten (or so) trees: The Centennial Elm

History Buzz contributor Jane Cairns shares the history of Elm Square's trees and sheds light on how Andover residents commemorated two wars: the Civil War (1861-1865) and World War I (1914-1918).

Who doesn’t love trees? They give us shade, purify our air and water, and provide homes for wildlife. They often provide the background to our favorite memories and, as recent research suggests, even boost our mental and physical health. As we look to them as examples of towering strength and old wisdom, they are also a useful metaphor to explore how scenes and episodes from one town’s history are interconnected with the larger world. This article is second in a series telling the stories of some of Andover’s best-known trees as well as the people who loved, planted, and nurtured them. Read the first installment (on Andover’s first apple tree) here.

The Centennial Elm

This is the story of more than one tree, and it starts in April 1865, eleven years before the celebration of the nation’s Centennial in 1876.

The first two weeks of that month were a time of great celebration in Andover, as in towns throughout the Northern states. News came first that the Confederacy’s capital of Richmond had fallen, and a week later on April 9 (also Palm Sunday, the feast day whose triumphal significance resonated with the predominantly observant and Christian nation) that Confederate General Lee had surrendered to Union General Grant at Appomattox, Virginia.

The Andover Advertiser described the town’s mood:

The news . . . has thrilled the country with mighty joy, and with thanksgiving to God who has given us this great victory. The fall of Richmond caused such rejoicing that many said and believed that it could not be surpassed; but the joy over Lee’s surrender far exceeded that over the fall of Richmond. We cannot expect to see the like again. It is not often given to any people to witness two such scenes in one generation, or one century. The whole loyal nation was in an ecstasy. Men assembled to give expression to their feeling, but language failed them; speech seemed contemptible; anthems, cheers, the ringing of bells and the booming of cannon were more eloquent than the finest oratory. 1

This pure, unqualified jubilation would end five days later, we know now, with the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on the evening of April 14 (Good Friday on the Christian calendar).

Andover nurseryman Daniel Cummings was one town resident who looked to commemorate these momentous occasions with a gesture more lasting than words. He tramped into the woods near his home sometime that week and, digging up two native elm saplings, transplanted one to his own yard, now 69 Salem Street, and one to that of his neighbor William Henry Foster, now 49 Salem Street. (Both houses, enlarged by subsequent owners, are still standing. Their histories can be viewed at https://preservation.mhl.org/69-salem-street and https://preservation.mhl.org/49-salem-street.)

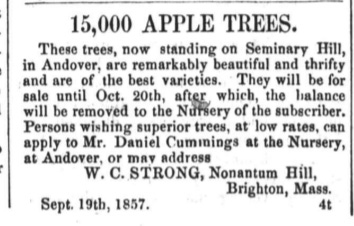

Cummings was thirty-six years old in 1865, with a wife Hannah and a nine-year-old daughter Luella. Descended from an old Andover family (though he had been born in Maine), he was well-connected in town. His brother Brainard Cummings was a sought-after carpenter and homebuilder, and his first cousin George Mooar was the South Church rector. Daniel had registered for the Andover draft in 1863, but was not selected and did not, like Brainard and another brother, serve in the military. As a younger man, he worked and boarded with members of the Farley family at the farm on the corner of Main and Phillips Street that supplied milk and eggs to the Phillips Academy dining commons. By 1857 he was using a portion of the Farley’s property to sell apple trees, as an agent for Brighton horticulturalist and entrepreneur William Chamberlain Strong (who may have been some relation of Cumming’s mother Lois (Chamberlain). 2

In the years following the war, Cummings became known around town for his broad knowledge of tree planting and care. As a local expert, he was tasked in 1876 by Andover’s Centennial Committee to find a suitable replacement for the original, double trunked “Great Andover Elm,” one of the trees removed ten years previously to help make way for Memorial Hall Library, the town’s tribute to its Civil War dead.

Felling the “Great Elm” had caused the consternation of at least one Andover resident, writing to the Andover Advertiser under the name “Civis” in April 1866. If the letter writer was not Cummings himself, it was someone who shared his sensibilities.

“Now, my Andover friends, that noble old tree is worth all the care of Andover men, select, and not select, to keep it alive. Bandage up its wounds, refresh its roots with new earth, and it will repay your generosity by a new and vigorous growth just as its younger colleagues have done on Boston Common and elsewhere. A tree that has outlived the threats of so many select men, and the fires of boys, deserves some reverence. It would be a shame to let such a tree dies of neglect. It would be most miserable mistake to cut down this aged witness of all the flames of war and peace that have ever passed over the town of Andover. The brave men whose monument you propose to erect under its shade will never thank you for violating this living monument of all the living and all the dead.”3

For the replacement tree that became “The Centennial Elm,” Cummings chose the sapling he’d planted in William H. Foster’s yard, finding it the slightly sturdier of the two he’d planted in 1865. With Foster’s agreement, he dug up the now eleven-year-old sapling and replaced it with his own.

The chosen tree was planted in the center of Elm Square on July 4, 1876 as part of an all-day ceremony. Booming cannons kicked off the morning’s events, followed by the ringing of church bells, including the first peals of Andover Theological Seminary’s “Centennial Bell” in its newly completed Stone Chapel. The annual Horribles Parade proceeded the length of Main Street to Elm Square, where a “choral union” of the town’s churches performed a hymn and George F. Wright, pastor of the Free Church, gave the day’s keynote address: “We plant here a tree which 100 years from now our children and children’s children will see as a symbol of hope in which our nation may abide.” Following the planting itself, the townspeople marched to Indian Ridge Grove, followed by veterans of the War of 1812 in carriages and the town’s steam fire engines, all elaborately decorated. Two thousand people danced and played sports through the afternoon, before the day concluded with a display of fireworks.

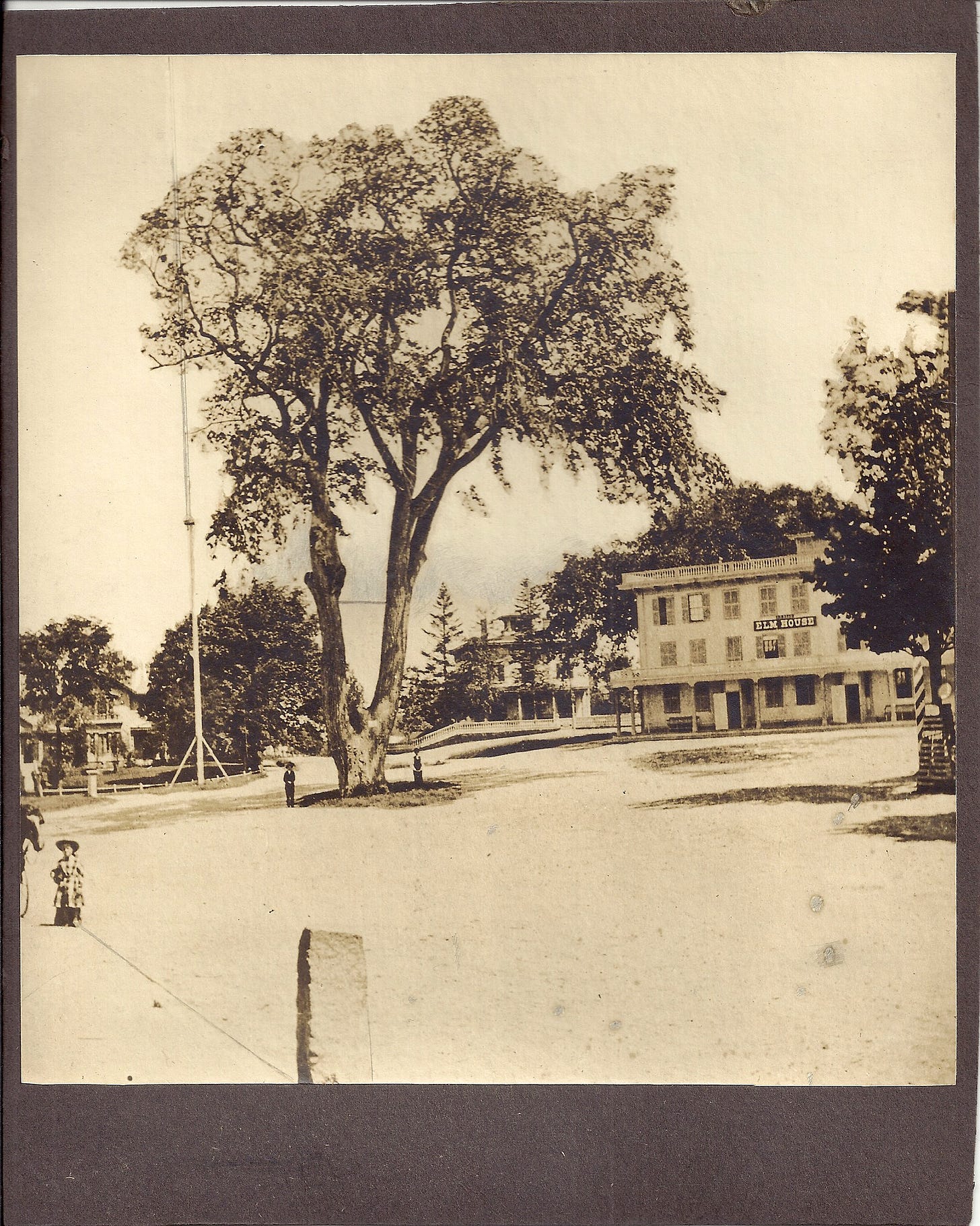

Photos of Elm Square in the first two decades of the 20th century show the tree as a key landmark, but as a lone planting in the middle of the heavily trafficked and compacted street, never flourishing as its predecessor had. Trolley tracks or “electric car lines” were installed within yards of its spreading branches beginning in 1891. The Andover Village Improvement Society (AVIS) constructed a “convenient seat” around three sides of the tree in May 1901, but automobile traffic soon displaced many of the pedestrians.

Rumors began as early as 1911 that the tree would soon be removed to accommodate double tracking on Main Street and only intensified in the years before WWI as it began to be considered a traffic hazard rather than a symbol of hope.

A new generation of tree lovers were again concerned. AVIS commissioned prominent Boston landscape architect Heber Bishop Clewley to determine if the tree could realistically be moved but, learning that the cost (more than $150) would be prohibitive and the prognosis for survival poor, sadly endorsed the tree’s removal. “Doubtless most of the older residents have a great deal of sentiment in regard to this tree,” the AVIS minutes read, “but if, as claimed, the tree has already been the cause of accidents and will always continue to be a menace, while in its present location, the sooner removed, the better.” 4

Americans were undoubtedly as happy and grateful toward the end of the “Great War” as they’d been at the end of the Civil War. The news of the Armistice (on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918) reached Andover at 3:50 am and a spontaneous celebration broke around the Centennial Elm that morning hours before daylight. The next September, the town staged a gala “Welcome Home” celebration with a parade down a decorated Main Street, complete with floats, band concerts and outdoor movies in the Park, and a banquet attended by Governor (and future president) Calvin Coolidge. But there was no denying that the War’s 20 million dead plus 50 million more lost in the 1918 influenza pandemic had left the national mood more world-weary than jubilant. Even the perennially romantic AVIS secretary and founder Emma Lincoln sounds less sentimental about the threat to the Centennial Elm when she writes in 1919, “Not for one instant can we weigh our feelings for a tree against the value of a human life.”

The elm that had been planted at the end of the Civil War was felled on December 5, 1919, a little more than a year after World War 1’s Armistice.

But this is the story, I said at the beginning, of more than one tree.

Whatever happened to the Centennial Elm’s twin, planted on the same day and switched by Daniel Cummings in its Salem Street “cradle?”

That tree still stands, its branches gnarled and pollarded by age and storms, its trunk covered in ivy. The Williams family now living at 49 Salem Street treasures this brave monument from another era.

More to come . . .

In the next entry of “Long Memories” I’ll share another story of a historic town tree. I love questions and comments. Click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

Thanks for reading!

Jane

History Buzz is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Andover Advertiser, April 15, 1865, (https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1865-04.pdf)

Andover Advertiser, Sept 19, 1857, p.2. (https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/AAD-1857-09.pdf)

Andover Advertiser, April 13, 1866, (https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/LAM-1866-04.pdf)

Annual Report of the Clerk for AVIS, Dec. 1919, (AVIS archives,ACHC collection)

The postcard with the dapper dudes sitting in the middle of Elm Square is hilarious. "Automobile traffic soon displaced" them is an understatement!

This is a wonderful exposition of elms, their importance in Andover's history and the many human characters involved. Thanks so much, Jane, for the great research and presentation. Looking forward to the next installment!