Carriage painting

While prepping a post on a portrait in the History Center's collection, I went down a research rabbit hole about carriage painting.

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, please sign up for a subscription to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

The last time we looked at a painting in the History Center’s collection, we talked about how some 19th century portrait painters had their first training as carriage painters. This tidbit fascinated me.

How did painting carriages prepare an artist for a career as a portrait painter? Aside from innate artistic talent, carriage painters were well-trained in using paints, pigments, and other materials needed to paint works of art. Some moved into portrait painting without any additional art training. Others studied with known portrait painters.

Carriage painting

We might think about carriage painting the way we might think about painting a car today. But back when horses, wagons, and carriages were a common mode of transportation, carriage painting was a different skill.

Carriage painters were often sign and house painters, as seen in these advertisements from the Andover Advertiser and Andover Townsman.

In his 1881 book House-Painting, Carriage-Painting and Graining,1 John W. Masury described the desired qualities of the carriage finish:

To show the best possible colors, the light must be reflected, not from a flat, opaque surface, but from a surface which has beneath it a depth of continuous colored particles reaching way down through the successive coats of varnish to the groundwork.

Carriage painters achieved this effect by applying layers of wood fill, paint, glazes, and varnish, smoothed between coats by sanding with a pumice stone.2 The application of these layers and the ground pigment, highlighted “the painter’s aesthetic abilities.”

Carriage painters ground and mixed their own paints.

To paint a carriage in the highest style of the art requires a judgment matured, an eye to appreciate combinations and contrasts, and a hand cunning and skillful to execute and perform. In nothing more than this is it true that practice alone makes perfect.

Gardner describes glazing this way:

The art of giving a ground-color a different shade or richness by coating it with a transparent glaze or thin wash. The pigment, such as carmine, ultramarine blue, etc. is mixed with varnish to form a sort of colored varnish, not a solid covering, and then applied the same as varnish to a ground quite near the color of the glaze.

Of course, the finishes on painted carriages and wagons had to be sturdy enough to survive the jarring nature of cobblestone and dirt roads. Up to two dozen layers of paint, glazing, and varnishes were required for a perfectly smooth finish that would stand up to roads. Weeks were needed to complete the job, in part due to the long dry times between layers of finishes.

In a chapter on “the old way of painting a carriage,” Masury instructs the reader to start the process by priming the raw wood with a mixture of ground white-lead, raw linseed oil, a drying agent, and “enough turpentine to make the paint work easily.” After working the mixture into the wood surface, the body of the carriage was left to dry for four days.

Putty was then applied to cover screw-heads and hollows in the wood. Open-grained woods, like ash, in particular needed a soft putty worked into the pores of the wood. More coats of lead followed, each drying three to four days in between coats.

After drying was complete, the whole carriage body was scrubbed or scoured using a lump of pumice stone that had been soaked in water.

After these layers, plus a few more . . .

“It will now be understood that the successive coats of paint, with the labor of rubbing and smoothing, have brought the surface to the best possible condition for receiving the first coat of color.”

After all that surface prep work it was time, as Masury wrote, for the “the painter’s aesthetic abilities” to shine.

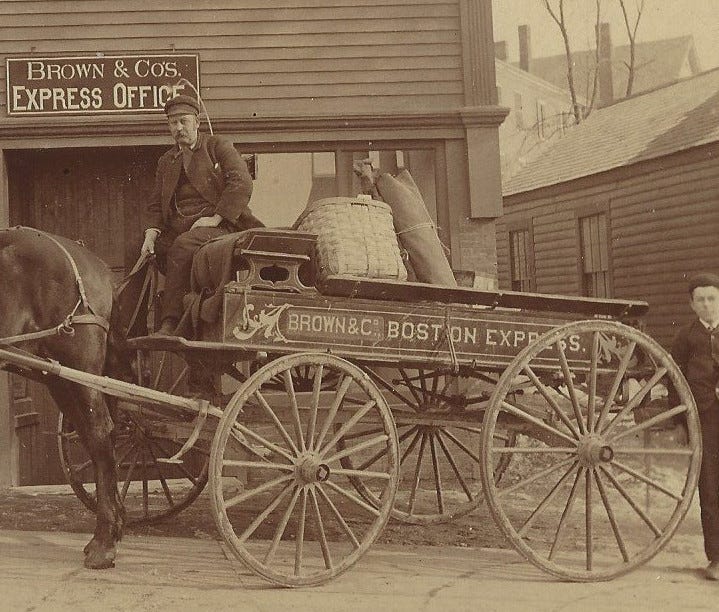

Carriage painting could be as simple as applying paint to the body of the carriage.

Or, it could be the name of a business.

Or, the wagon could be more elaborately painted.

We don’t have any painted wagons or carriages in the collection, but we do have a painted Hunneman fire pumper. You can read more about the history of the fire pumper here.

The automobile marked the end of the carriage painter’s industry, but the form of the carriage was continued in early automobile design.

Thanks for reading! My quick dive into carriage painting was a rabbit hole I went down while prepping to share a painting in the History Center’s collection. It was painted by the artist James Frothingham, who started his career as a carriage painter. More on the painting, its subject, and the artist is coming soon.

~Elaine

Masury, John W., House-painting, Carriage-painting, and Graining: What to do and how to do it, 1881: https://books.google.com/books/about/House_painting_Carriage_painting_and_Gra.html?id=bDMZAAAAYAAJ

Getty Insitute, Conservation Publications, Painted Wood: History and Conservation: https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/paintedwood4.pdf

Another fascinating article, Elaine. I especially liked the information about the collection items.

The Elm Square fire involved a carriage business. Highly flammable materials. And all that lead. I'm thinking about the changes in paint and painting that have occured over the centuries. These days one can put ceramic coating on to help protect the paint work.