Andover Bewitched: "The distressed condition of our wives and relations in prison..."

How did Andover residents help end the panic of the 1692 witch trials?

The last people hanged for witchcraft were executed in September 1692, and though more people awaited trial or remained in prison, the swell of panic had begun to fade. Members of Andover fought for the release of their family members and for the return of peace. In the years that followed, grieving and harmed families sought financial compensation and a formal apology from the government.

Want an introduction to the 1692 witch trials? Try the first entry in this series!

The 1692 witchcraft trials were not like other legal cases at the time. Part of what set these trials apart was the hasty establishment of a special court. Faced with an overwhelming number of cases, the Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, Sir William Phips, created a court dedicated to the “outbreak” of witchcraft in Essex County. A Court of Oyer and Terminer, a title which means “to hear and determine,” can be created to hear serious crimes, like that of witchcraft.

Phips appointed William Stoughton as the chief justice of the new Court of Oyer and Terminer in June 1692, with several other judges to serve under him. Samuel Sewall, one of these judges, would later apologize for his role in the trials.1 Stoughton collected a jury of 40 Essex County men to hear the cases.2

It was this court and this jury, held in Salem Town (Salem today), that judged each case during the 1692 trials. Anyone accused in Andover was brought to trial in Salem because of the centralized special court. In addition, because of that centralization, the court had a lot of power; Chief Justice Stoughton allowed spectral evidence, or testimony of dreams and visions.

By October 1692, after hundreds of trials and over twenty deaths, Governor Phips reassessed the situation. He dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer and established a new court which would not allow spectral evidence.3

Stoughton was once again placed in charge of the new court. Initially, he went ahead with a similar intensity, writing out execution orders. But Governor Phips stopped him, pardoning those condemned and removing Stoughton from the new court.

Why did Governor Phips end the Court of Oyer and Terminer?

There are many reasons why the Governor might have changed his mind about Judge Stoughton’s free reign in the Court of Oyer and Terminer. Perhaps the most obvious reason is that his family member was accused of witchcraft. He also certainly saw the bubble and panic of hysteria spreading across the county and, like many others, worried about just how far it could go before it stopped.

Phips’ decision may also have been a result of several emotional letters penned by Andover residents!4

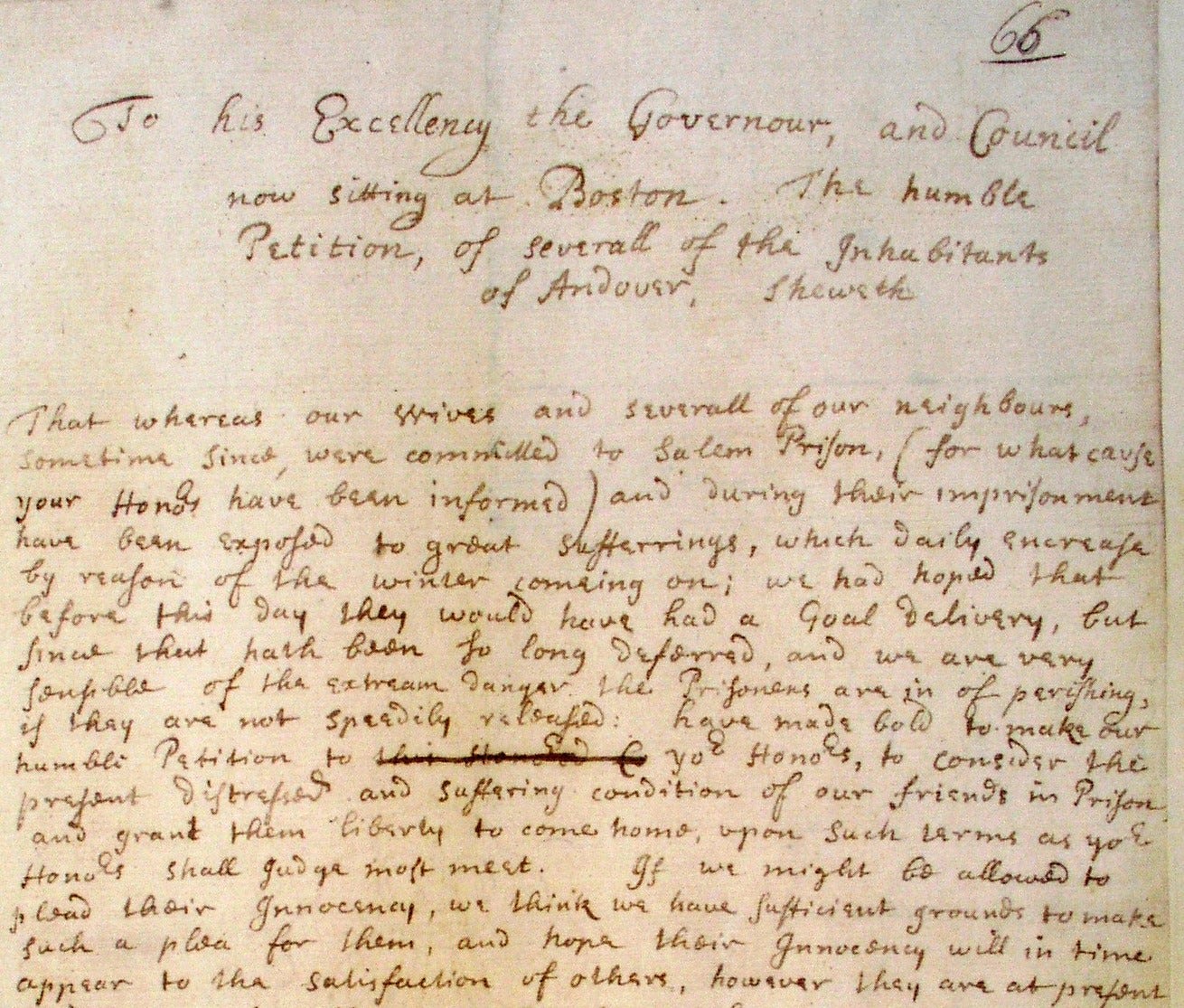

On October 12, 1692, John Osgood and eight others petitioned the courts:

“It is the distressed Condition of our wives and relations in prison at Salem who are a company of poor, distressed creatures as full of inward grief and trouble as they are able to bear up in life… and besides that aggravation of outward troubles and hardships they undergo: wants of food…and the coldness of the winter season that is coming…”5

He writes poignantly about the struggles of his wife and family. “They have not been used to such hardships,” he pleads. It must be true; the prison was cold and the prisoners were not especially well fed. In fact, an Andover woman, Ann Foster, later died in the same Salem prison.6

The letter asks that those imprisoned be sent home to “remain as prisoners under bond of their own familys where they may be more tenderly cared for.”

The letter was signed by John Osgood, John Frey, John Marston, Christopher Marston, Joseph Wilson, John Bridges, Hopestill Tyler, Ebenezer Barker, and Nathaniel Dane.7

Six days later, even more members of Andover gathered to compose a second letter. Rather than call for those imprisoned to be returned home, this letter asks for an end to the trials.

“Our troubles which hitherto have been great, we foresee are like to continue and increase, if other methods be not taken…There are more of our neighbors of good reputation & approved integrity, who are still accused, and complaints have been made against them. We know not who can think himself safe if the Accusations of children and others who are under a Diabolical influence shall be received against persons of good fame.”8

Whether it was these letters, or others aspects of the rapidly spiraling hysteria that led Governor Phips to end the Court of Oyer and Terminer and the use of spectral evidence, he did so.

Though trials continued, there were no further executions and the hysteria dissipated almost as quickly as it had descended. It seems that the dissolution of this special court and the banning of spectral evidence soothed much of the panic.

How could Essex County heal the harm caused by the witchcraft trials?

While the immediate threat of execution was stayed by Phips’ change of heart, the accusation of practicing witchcraft was a stain on anyone’s head. Plus, court fees and time in prison had cost those accused and their families a great deal, financially and socially.

Read Abigail Faulkner’s story for her fight for restitution and the return of her good name – Abigail was afraid that her conviction of practicing witchcraft could be brought up again if anything like the 1692 hysteria resurfaced.

In 1702, less than ten years after the conclusion, the Massachusetts courts declared the trials unlawful. Others, like Ann Putnam, one of the young Salem girls who accused many, offered a public apology and a retraction of her accusations. Ann Putnam may have been involved in the indictment of several accused in Andover including members of the Lacey family.

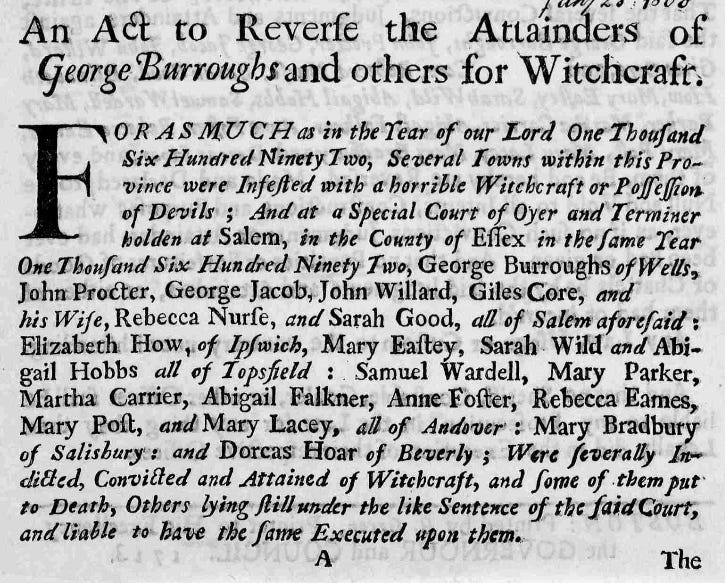

Finally, in 1711, “An Act Made and Passed by the Great and General Court or Assembly of Her Majesty’s Province of the Massachusetts Bay in New England,” reversed the convictions of many accused.9

“The influence and Energy of the Evil Spirits so great at that time acting in and upon those who were the Principal Accusers and Witnesses, proceeding so far as to cause a Prosecution to be had of persons of known and good Reputation, which caused a great Dissatisfaction and a stop to be put thereunto…”10

Queen Mary granted that in all future trials, “all due Circumspection be used” and “the greatest Moderation.” The Act cleared the names of many convicted, including several Andover residents: Martha Carrier, Abigail Faulkner, Ann Foster, Mary Lacey, Samuel Wardwell, and others, though cases to clear more names have continued to this day, most recently for Elizabeth Johnson Jr.11

The 1711 act also began the restitution process — the government’s disbursement of money in apology for the harm caused by the trials. Those who had paid court fees, or who had property seized, or spent time in jail, or lost a family member, wrote a plea for restitution and in most cases, seem to have received it.12

Thomas Carrier, for example, wrote out the costs incurred while his wife and children were imprisoned and his wife Martha was executed:

I payd to the Sherriff upon his Demand fifty Shillings.

I payd the prisonkeeper upon his demand for prison fees, for my wife and four children four pounds Sixteen Shillings.

My humble request is that the Attainder may be taken off; and that I may be considered as to the loss and damage I Sustained in my Estate.13

He received all the sums he had requested.

But, neither clearing Martha’s name nor this financial compensation could take back his family’s suffering while his young children were imprisoned and his wife was executed at the hands of the court for that which she did not do.

Thank you very much for reading this week’s installment of Andover Bewitched on History Buzz! Tune in two weeks from now for the next entry of Andover Bewitched.

If you have any questions, or if there’s any aspect of the trials you’d like to learn more about, leave a comment! I’d love to hear from you. Click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

— Toni

A transcription of Sewall’s detailed diary is found here, or in the original at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Warrant for Jurors for the Court of Oyer and Terminer, via Salem Witchcraft Papers from the Essex County Court Archives, University of Virginia.

Smithsonian Magazine, “A Brief History of the Salem Witch Trials” (2007).

Reverend Francis Dane wrote an additional letter in January 1693 condemning the use of spectral evidence. Read this letter here and his story in our series here. At the time, Andover included the Village Center, where Dane lived. In 1709, the North Parish was formed, and much later, in 1855, Andover and North Andover split along the parish lines — Dane lived in what is now North Andover.

See Sarah Loring Bailey, “Witchcraft at Andover” (esp. pages 213-216) in Historical Sketches of Andover.

These same men, sans the Marstons, wrote an additional letter in December 1692 asking for their loved ones to be returned home. They ask the judges “to consider the present distressed and suffering condition of our friends in Prison and grant them liberty to come home.”

Here is an original list of just some of the restitution money requested by those impacted by the trials. Martha Carrier, Samuel Wardwell, and Mary Parker all appear in the top section, Abigail Faulkner and Ann Foster in the second, and more Andover residents in the bottom section.

Petition of Thomas Carrier for Restitution for Martha Carrier, Salem Witchcraft Papers.

Neil Vigdor, “She Was Declared a Witch at Salem. These Middle Schoolers Want to Clear Her Name,” New York Times, August 2021

Thanks Toni for another interesting slice of 1692!