Andover Bewitched: Too little, too late?

Ann Putnam Jr. and Judge Samuel Sewall apologized for their involvement in the trials. Could you forgive them?

In the two decades following the 1692 witch trials, accusers and accused alike struggled to readjust. For some, life went back to normal. The residents of Salem Town, Andover Village, Topsfield, Gloucester, and elsewhere returned to their farms and continued to live ordinary lives. And yet, the community as a whole did not — could not — forget the stain of the witch trials. In today’s edition of “Andover Bewitched,” I’ll talk about the aftermath, detailing three key public apologies.

Want a refresh on the story of the trials? Start with the first “Andover Bewitched!”

How It All Went Wrong…

In the last “Andover Bewitched” post, I wrote about Martha Carrier, who was perhaps Andover’s most well-known witch trials victim. I’ll continue to highlight Martha’s trial to set the stage for our three apologists.

From the accusers to the courts to the legal grounds for a witchcraft accusation, the system failed the residents of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Martha Carrier’s story shows each of these pressure points: her accusers took up false claims against her, and court judges, like Samuel Sewall, permitted spectral evidence to finalize her conviction.

In Andover in early 1692, word of Salem Town’s witchcraft outbreak spread. Martha Carrier was first accused of practicing witchcraft by her neighbors, who already had it out for her and her family.1

As Martha’s trial continued, others joined in to testify against her, as was unfortunately common in these proceedings. Once brought to the stands, the only thing that could save someone was a confession of guilt.

In Martha’s case, she refused to confess to a crime she did not commit. So the young girls, who were supposedly suffering from the effects of witchcraft, were brought to the stand to testify against her. They claimed she had haunted them and that her image was causing them real bodily harm.

The afflicted girls, including Ann Putnam, Mary Walcott, and others, referenced the infamous Andover mythology that the Carrier family had brought a smallpox epidemic to Andover in 1690. The epidemic killed thirteen people, so Putnam and the others claimed to see the victims:

Susan Sheldon cried out in a trance: I wonder [how] you could murder 13 persons?

Mary Walcott testified the same: that there lay 13 ghosts.

All the afflicted fell into the most intolerable outcries and agonies.

Elizabeth Hubbard and Ann Putnam testified the same: that she had killed 13 at Andover.2

Martha tried to protest, saying: “It is a shameful thing that you should mind these folks that are out of their wits.”3 Her protests went unheard: the trial continued, and the girls’ visions served as legitimate evidence against Martha.

The Judge: Do you not see them?

Martha: If I do speak, you will not believe me.

You do see them, said the accusers.

Martha: You lie, I am wronged.

There is the black man whispering in her ear, said many of the afflicted.4

Martha’s trial was only one among many where the voices of the afflicted girls swayed the courts’ decisions; so many others were guided by these testimonies because the courts believed that girls’ visions were legitimate evidence.

The trials were held in front of a jury of nine judges specially selected to serve in these cases of witchcraft. Samuel Sewall was one of these judges, and like the others, he participated in the complicated early colonial legal system. These judges, Samuel included, believed that spectral evidence — testimony about supernatural apparitions — was legitimate grounds for an accusation.

Though spectral evidence and the court’s processes were later reassessed, it was too late for those executed for witchcraft. In the years following the trials, only two people made public apologies. The Massachusetts Courts began to clear the names of those convicted of witchcraft in 1703, but these legal efforts have continued to this day.

Ann Putnam Jr. made a public apology in 1706…

In 1706, 27-year-old Ann Putnam Jr. made a public confession apologizing for her behavior during the witch trials. Ann was a key witness during the trials; she was one of the earliest among the girls to begin accusing her neighbors.5 She was only thirteen in 1692 and yet her testimony led to the execution of several of her neighbors, including Martha Carrier, Rebecca Nurse, Mary Eastey, and others.

Here are a few excerpts of Ann’s short confession, read aloud in church before the Reverend Joseph Green of Salem Town:6

"I desire to be humbled before God for that sad and humbling providence that befell my father's family in the year about '92; that I, then being in my childhood, should, by such a providence of God, be made an instrument for the accusing of several persons of a grievous crime, whereby their lives were taken away from them, whom now I have just grounds and good reason to believe they were innocent persons...

Whereby I justly fear I have been instrumental, with others, though ignorantly and unwittingly, to bring upon myself and this land the guilt of innocent blood... And particularly, as I was a chief instrument of accusing the Goodwife Nurse and her two sisters, I desire to lie in the dust… earnestly beg forgiveness of God, and from all those unto whom I have given just cause of sorrow and offense, whose relations were taken away or accused.”7

Ann Putnam was the only one of the accusers to make such a formal and public apology. Was she trying to resolve her own conscience? Was she concerned for the guilt of her soul? The apology reads far more as an ask for her neighbors to forgive her rather than God, as she ends by asking for forgiveness from “all those unto whom I have given just cause of sorrow or offense.”

By 1706, much had changed in her life. Her parents were deceased and she was the primary caretaker for her many younger siblings. Her health had not much improved — Ann would actually pass away at only 36-years-old in 1716.8 And the community had changed too. By 1702, the Massachusetts Bay Colony had reversed the convictions of those accused of witchcraft. Perhaps the decade of soul-searching was enough to move Ann to apologize.

Samuel Sewall was the only judge to formally apologize…

Judge Samuel Sewall was more liberal than many of his clergy peers, and yet, he was involved in the trials as a lead judge. He was appointed by the governor and served out his term in the special courts convened for the trials.

Samuel, along with the eight other judges, convicted over twenty people of practicing witchcraft and oversaw their executions. He must have believed strongly in the truth of the accusations, as he did not hesitate to carry out the legal proceedings.

In 1696, Sewall was the first and only one of the nine judges to publicly apologize for his involvement:9

“Samuel Sewall, sensible of the reiterated strokes of God upon himself and family; and being sensible, that as to the Guilt contracted, upon the opening of the late Commission of Oyer and Terminer at Salem (to which the order for this Day relates) he is, upon many accounts, more concerned than any that he knows of, Desires to take the Blame and Shame of it, Asking pardon of Men, And especially desiring prayers that God, who has an Unlimited Authority, would pardon that sin and all other his sins...”10

This was a bold and risky move because it meant admitting his guilt at a time when none of the fellow judges had done so. It was only in 1695 that others in power had begun to speak out so explicitly about the injustices of the trials, and none who had been directly involved in the legal system.

Sewall’s apology, plus the strong oppositions of others (like Robert Calef, who I wrote about here), seem to have encouraged the General Courts towards a more significant legal apology. In early 1697, the Massachusetts ministers held a day of fasting in memory and honor of the 1692 trials.11

And later legislation — in 1702 and 1711 — formally cleared the names of the convicted and created funds for restitution to their families.12

The Massachusetts General Courts cleared more names in 1957…

Finally, in 1957, the Massachusetts General Court issued a formal apology and cleared the names of other people accused of witchcraft during the trials.13 This was over 250 years after the trials. The court system, especially the permission of spectral evidence, led to such widespread convictions and executions.

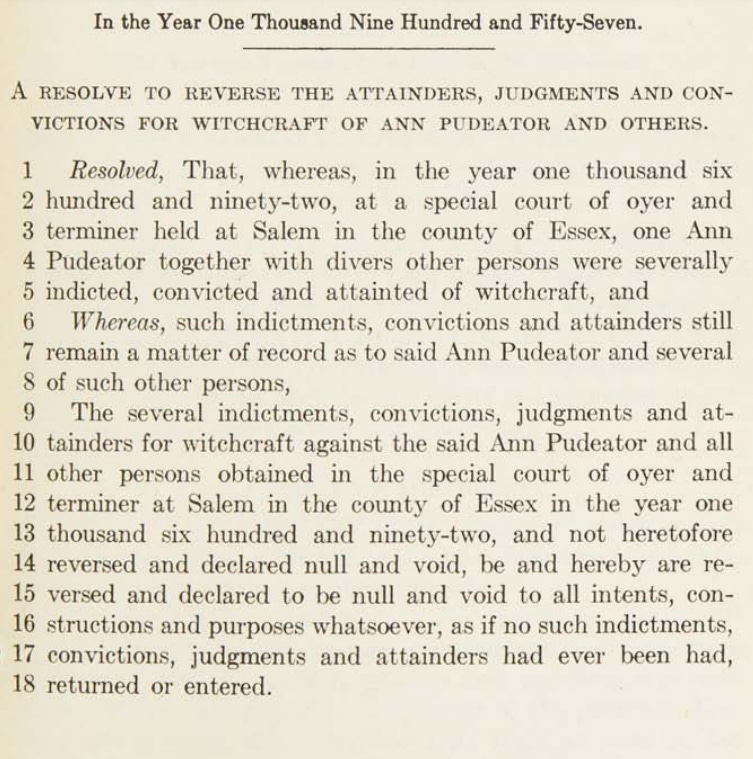

The 1957 act reversed the judgements of Ann Pudeator and several other “diverse persons” accused of witchcraft in 1692:

“The several indictments, convictions, judgments and attainders for witchcraft against the said Ann Pudeator and all other persons obtained in the Special Court of Oyer and Terminer at Salem in the county of Essex in the year one 13 thousand six hundred and ninety-two, and not heretofore reversed and declared null and void, be and hereby are reversed and declared to be null and void to all intents, constructions and purposes whatsoever, as if no such indictments, convictions, judgments and attainders had ever been had, returned or entered.”14

This wasn’t the only legal reversal, but it was an important one because it came only four years after Arthur Miller published The Crucible (1953). This play brought the Salem witch trials to the forefront, renewing the horrors of the trials in his dramatized account.

In 2001, another five people were posthumously cleared, striking their convictions from the court record. There is still one more name to clear: Andoverite Elizabeth Johnson Jr. who was convicted for practicing witchcraft but not executed.15

From the courts, to the judges, to the accusers who participated in the trials, the system failed the residents of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. We’re still grappling with the challenges of finding closure even three hundred years after the trials.

Samuel Sewall and Ann Putnam caused real harm, but we can also appreciate their bravery for publicly acknowledging the damage they did. And we can still see the ways that the laws of today are affected by history, even more than three hundred years later.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed reading about Ann Putnam today, you may also like Annette Laing’s entry on Rebecca Nurse. I had a great time reading this piece, and I’m sure you will too, so check it out here on Non-Boring History.

And in the meantime, if you have any questions, or if there’s any aspect of the trials you’d like to learn more about, leave a comment! I’d love to hear from you.

Click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

—Toni

Juliet Haines Mofford, Andover Massachusetts: Historical Selections From Four Centuries (Merrimack Valley Preservation Press: 2004).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Joseph Green took over after Samuel Parris was forced to resign from his position. Parris had served as the pastor during the trials and was a strong supporter of their continuation.

Read the confession via Rev. Joseph Green Church Records (August 25, 1706) Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive. The confession is also described in Annette Laing, “Rebecca Nurse is Canceled: Salem, 1692.” And see Rebecca Brooks, “Ann Putnam, Jr.: Villain or Victim?” History of Massachusetts (July 2015).

The Reverend Samuel Parris, who had been heavily involved in the convictions, made an apology within a sermon he gave in 1694, dubbed “Meditations on Peace.” However, this apology mostly blames other people (in his words, the Devil entered other people to cause their frightening behavior), and he offered it while the courts were bringing charges against him for his involvement in the trials.

“Salem Witchcraft Trials,” Massachusetts Law Library, October 2015.

1957 House Bill 1775. A Resolve To Reverse The Attainders, Judgments And Convictions For Witchcraft Of Ann Pudeator And Others (1957). State Library of Massachusetts.