Andover Bewitched: Susannah Post on Trial

How did Susannah shape her confession to protect herself and her 13-year-old sister? Read today's entry to find out!

Today, I’ll share Susannah Post’s story. She was accused of witchcraft and arrested, and survived due to her detailed confession. Susannah was very smart and used her confession to carefully shift blame away from herself (and her little sister), without adding to too much other hysteria. If you’d like a summary of the full 1692 witch trials, start with the first entry in this series.

The Salem judges said that Susannah Post had afflicted Martha Sprague and Rose Foster using witchcraft. The two girls had accused many people in Andover and beyond – Susannah was just one more person on the list.

Susannah was arrested in late August at her home in Andover Village, now North Andover. She was brought to Salem to stand trial in the large “Court of Oyer and Terminer,” a special court dedicated to the witchcraft epidemic spreading through the Massachusetts Bay Colony.1 The court had special dispensation to bring in judges from across the colony, and was charged with finding and executed any witches.

On August 25, Susannah Post stood before the courts.2 Major Bartholomew Gedney was in the judges’ stand – he was descended from one of the early settlers of Salem.3 There were certainly other judges in attendance too, perhaps Samuel Sewall or others.

There were other important court members too, like Simon Willard, the court attestator, Captain John Higginson, a court officer, and Robert Payne, the foreman. Payne probably brought Susannah into the busy courthouse from the cold basement jail. There were other trials held the same day, so maybe she sat among her neighbors – watching their trials and waiting for her turn.

Susannah was accused of practicing witchcraft on her neighbors…

When she finally took the stand, the courts told her that she was accused of afflicting Martha Sprague and Rose Foster. The courts brought Martha and Rose before Susannah: they were “greatly afflicted” by her presence. And Mary Warren, another afflicted teenager “recovered” from her ailments when Susannah touched her.4

Mary, Martha, and Rose “charged her with afflicted them” and claimed that they saw her do it. Susannah’s own sister, Hannah, claimed that Susannah had been “baptized” by the Devil with her.5 All of this testimony was strong evidence against Susannah, even though it was just word of mouth – the evidence of the girls’ affliction was taken very seriously.

At first, Susannah denied the accusations. Can you imagine standing in that courtroom? Wealthy, highly respected judges and clergymen stood on one side of the room. They claimed that Susannah must be a witch – the evidence was clear! Just look at the girls in pain: across the room, the afflicted girls suffered and continued their accusations.

Susannah’s own family had turned against her. She’d been taken from her home and kept in a cold, uncomfortable jail cell. And now she was on trial for her life!

Under pressure from the judges, Susannah confessed to witchcraft…

When anyone confessed to witchcraft, they had to explain how they got involved with the Devil. They’re usually fantastical, involving all kinds of bizarre interactions with the Devil and the supernatural world. And the stories inspired each other – each accused person listened to other trials and shaped their stories to match.

“She confessed she had been in the Devils snare for three years. The first time she saw him, he was like a cat. He told her he was a prince, and “I was to serve him. I promised to do it.”6

Again, the Devil returned to her, next as “yellow bird” who told her to serve him and “live well.” Other confessions claimed the Devil looked like a bird or a “black man” (meaning in shadows, not a racial category), that he came in the night and encouraged the witch to “serve him.” The Devil’s capacity to shapeshift was a marker of his untrustworthiness – it meant that anything could be the Devil and anyone could be seduced into committing wrongdoing.

But seeing the Devil wasn’t the real crime. The third time Susannah Post supposedly saw the Devil, he:

“brought a book and she touched it with a stick that was dipped in an ink horn and it made a red mark...” 7

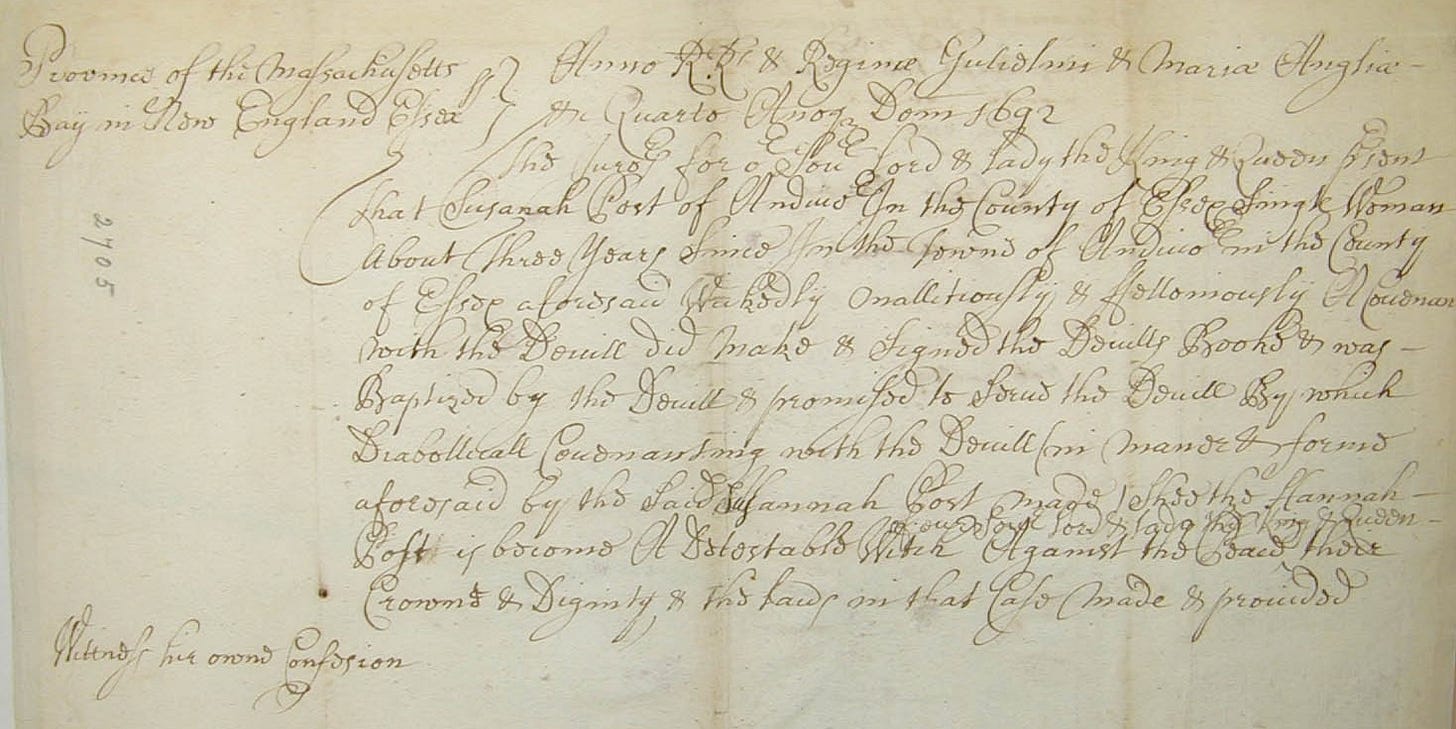

This is when Susannah made a deal with the Devil, so to speak, the moment when she agreed to work with him. The Puritans believed that this so-called “covenant” allowed the Devil to control Susannah, to work through her to cause harm on other people at the Devil’s will. Later, Susannah’s indictment read:

“[Susannah] wickedly, maliciously, and feloniously [did make] a covenant with the Devil and signed the Devil’s book and was Baptized by the Devil and promised to serve the Devil by which Diabolical Covenanting [has] become a Detestable Witch.”8

Through consorting with the Devil, Susannah began to afflict her neighbors. Though she denied hurting Martha Sprague and Rose Foster, she did say she hurt her little sister, Mary Bridges “by sticking pins into cloth.” Perhaps Susannah was trying to protect 13-year-old Mary, who had also been accused and arrested — if Susannah was the witch and not Mary, then Susannah would take the fall and protect her little sister.

Susannah had to accuse others…

While confessing to witchcraft often protected the accused, it also meant that they had to indict others too. Susannah confessed and said she was willing to “renounce the Devil,” begging forgiveness from the afflicted. After she apologized, “she could come to them and not hurt them,” a sign that her soul could be saved.9

But even if Susannah was safe, she had to finish her confession to escape the end of the trials. The judges asked her who else was a witch. She said that she had been “baptized at 5 Mile Pond” (now Spofford Pond), where:

“There was a minister that said he was to be executed, but he was jolly joyful enough; he bid them do as he did – not confess – and they should be happy.”10

This was a very smart confession. George Burroughs, a minister in Salem, had been executed for witchcraft only six days earlier. Susannah probably knew about this – and accusing George Burroughs meant she could avoid accusing someone else who was still alive. Like her confession to hurting her sister, Susannah was careful in her language, trying her best to work within the system.

Susannah made up a story about a “witch meeting at Andover” with 200 other witches, where they ate white bread and drank red wine.11 Maybe Susannah thought that confessing to this meeting would help her avoid naming names, but the judges pressed on.

Eventually, she gave the following names: a Wilford of Haverhill, Sarah Parker, “the two Jacksons,” and Mr. and Mrs. Howard of Rowley. Wilford and Parker had already been arrested by the time Susannah was on trial.12

John Jackson Sr., John Jackson Jr., and John Howard, were all arrested on the same day as Susannah’s interrogation.13 Did her confession lead to their arrest? Or did she pick out familiar names because she had just seen their arrests? In any case, all three men survived the trials — and so did Susannah.

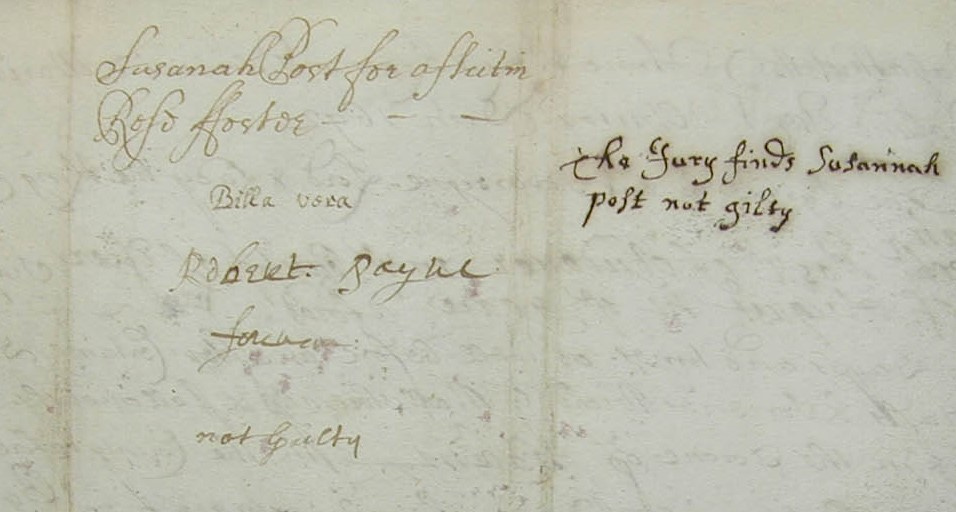

In May 1693, Susannah was re-tried and found not guilty. She was released from jail and the courts paid her fees. It’s not clear what happened to Susannah after that. She probably returned home with her family and continued to live in Andover, like many of the accused who survived the trials.

Thank you for reading, and as always: stay tuned for more entries of Andover Bewitched!

I’m excited to hear from you, so if you have any questions or if there’s any aspect of the trials you’d like to learn more about, leave a comment.

Plus, click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

— Toni

Hurd, History of Essex County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches, 1888.

Marilynne K. Roach, The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege, (London, Eng: Taylor Pub, 2004).

See Sarah Parker, “Petition of Sarah Parker for Restitution” January 22, 1712. Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive, University of Virginia.

Fascinating telling of the story, Toni!