Andover Bewitched: Sarah Lord Wilson

Read Sarah's story of endurance, while outside of the Salem prison, her husband fought for her freedom.

44-year-old Sarah Lord Wilson was arrested on the assumption of witchcraft on September 7, 1692. She was imprisoned and questioned, pressured to confess, and ultimately released. In today’s edition of “Andover Bewitched,” read Sarah’s story as she survived imprisonment and as her husband fought for her release. For a summary of the trials and Andover’s involvement, read the first “Andover Bewitched” here.

On September 7, 1692, officials gathered people young and old, rich and poor, from all across Andover. They brought as many people as they could find to the town’s meeting house. There, several of the afflicted girls from Salem were waiting under the watchful gaze of Justice Dudley Bradstreet.1

One by one, Andover’s constables led the members of the town to interact with the afflicted girls. Each person was asked to put their hands on the girls. If the girls’ illnesses ceased, then the person must be a witch… and if not, then they were innocent.2

When Sarah laid her hands on the girls, their afflictions must have stopped, because Sarah was immediately arrested and charged with witchcraft. Sarah’s 14-year-old daughter (also named Sarah) was arrested too — they may have ridden in the same carriage on the way to the Salem jail.3

When you think of a “witch hunt,” you might imagine pitchforks in the dead of night, but Andover’s hunt was in the daytime. This town-wide “touch test” was insidiously effective: eighteen people were arrested on September 7. So many people were arrested that Andover’s Justice Bradstreet could not bear it. He quit the next day and fled the town, refusing to indict anyone else on suspicion of witchcraft.

Let’s step back for a moment to the start of Sarah’s story. Why was she arrested? And why did the town host this hunt?

Sarah was the daughter of Robert Lord and Mary Waite, born in Ipswich, Massachusetts in 1648. The Lord family was well-known and well-respected, as Robert Lord worked as a Town Clerk. In 1678, Sarah married Joseph Wilson, a widower from Andover.4

After their marriage, Sarah and Joseph lived together in the south part of then-Andover, not far from the town center. They were engaged with the church and appeared to have no conflicts with their neighbors. Joseph worked as a cooper. By 1692, Sarah and Joseph had four children; the oldest was Sarah Jr. (14) and the youngest was Abigail (4).

Some analyses of Andover’s “touch test” argue that Pastor Barnard, a town leader, used the test to gather more evidence against Abigail Dane Faulkner.5 If this is true, Barnard expected that those accused would turn against Abigail and accuse her of leading them to the Devil. Abigail had given only a partial confession, and there wasn’t quite enough evidence to convict her.

You can read Abigail’s story in full here. During their examinations, Sarah Jr. — along with several other Andover children — testified that Abigail had led her into practicing witchcraft.6

After their examinations, Sarah Sr. and her daughter were kept in jail in Salem, awaiting further trial. Outside their doors, the last round of executions occurred. Abigail Dane Faulkner narrowly survived due to her pregnancy despite the town’s accusations against her.

And back home in Andover, the town was petitioning the governor to release their families. Countless children were arrested during the trials, often used as witnesses against their parents and other neighbors. They were kept in poor jail conditions and pressured by authorities to confess to crimes they hadn’t done.

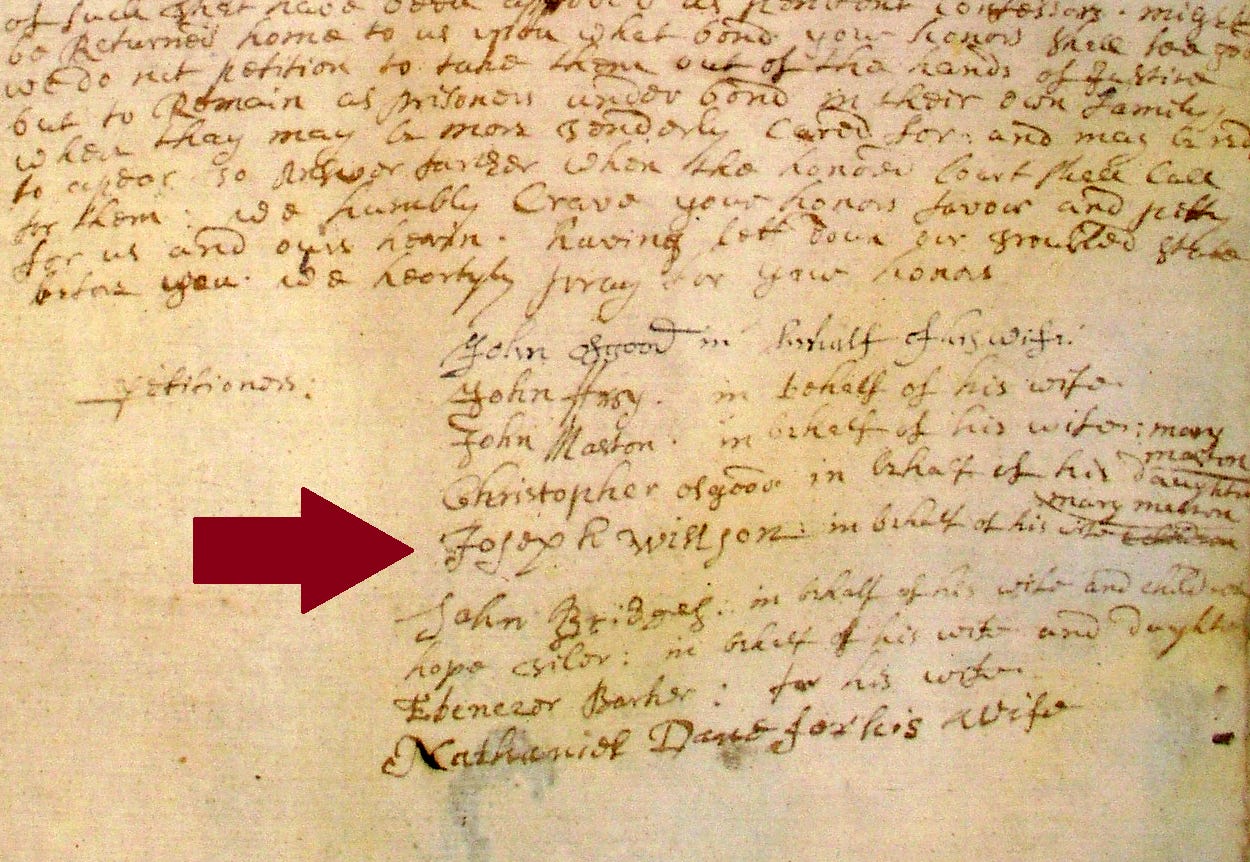

In a letter from several Andover men, including Sarah’s husband Joseph, they implore the Governor to release their families on bail:

“It is the distressed condition of our wives and relations in prison at Salem who are a company of poor, distressed creatures as full of inward grief and trouble as they are able to bear up in life… the aggravation of outward troubles and hardships they undergo: wants of food… and the coldness of the winter season that is coming may soon [hurt those] that have not been used to such hardships..”7

In response, on October 15, many of the Andover children were released, including 14-year-old Sarah Wilson Jr. She returned to her father in Andover after six weeks in prison, but Sarah Sr. was left behind.

The Andover residents petitioned again in October, and for a third time in December, begging for their families to be allowed to come home as winter set in and the weather grew colder and colder.

Finally, in early January of 1693, Sarah Lord Wilson Sr. was released on bail. She returned to Andover with her family and her four children. Though she still expected to stand trial, she was no longer forced to remain in jail.

By the time Sarah and her daughter went to trial in May 1693, the bloodlust of 1692 had faded away. They were both pronounced “not guilty” and sent home.

In 1711, Joseph petitioned for restitution for his wife and daughters’ jail fees among other victims and their families.8 Though there is no receipt for payment, it’s likely Joseph received these funds, since most of those who petitioned were granted what they requested.

Though it could have been so much worse, the Wilson family survived mostly unscathed and returned to their normal lives. Joseph and Sarah continued to live in Andover. Joseph Wilson died in 1718, and Sarah in 1727. John Wilson, Sarah and Joseph’s son, married the granddaughter of another witch trial victim (Mercy Wardwell Wright) and began his own family in Andover.

When interviewed about what she said while being examined, Sarah Wilson said that she “never had any familiarity with the Devil” and that “the afflicted persons” who accused her “made her fearful of herself.”9 She was scared — not only of her neighbors — but of the potential for darkness in herself, made so much worse by the terrible conditions she endured while imprisoned. Though she survived the trials, I cannot imagine the fear she went through waiting for those she trusted to decide her fate.

Thank you for reading! If you would like to learn more about the 1692 witch trials, stay tuned. Let me know your questions or ideas in the comments below. I love to hear from you!

Plus, click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

—Toni

See “The Andover Touch Test,” in Juliet Haines Mofford, Andover, Massachusetts: Historical Selections from Four Centuries (Merrimack Valley Preservation Press, 2004), p. 33-34.

See Enders Anthony Robinson, Genealogy of Andover Witch Families (Goose Pond Press, 2017).

Sarah is one of my ancestors on my dads moms side, and I just found out through ancestry but Sarah Jr is the one who continued my family line. I can not believe that one of my distant relatives went through this. Sarah Sr is my 11th great grandmother, and Sarah Jr is my 10th.

A sampler Sarah Sr. Crafted in 1668 is on display presently in New Jersey at the Salem County Historical Society.