Andover Bewitched: 9 Myths about the Witch Trials

Sometimes the stories of the 1692 witch trials can feel more like fiction! Here are a few common misconceptions.

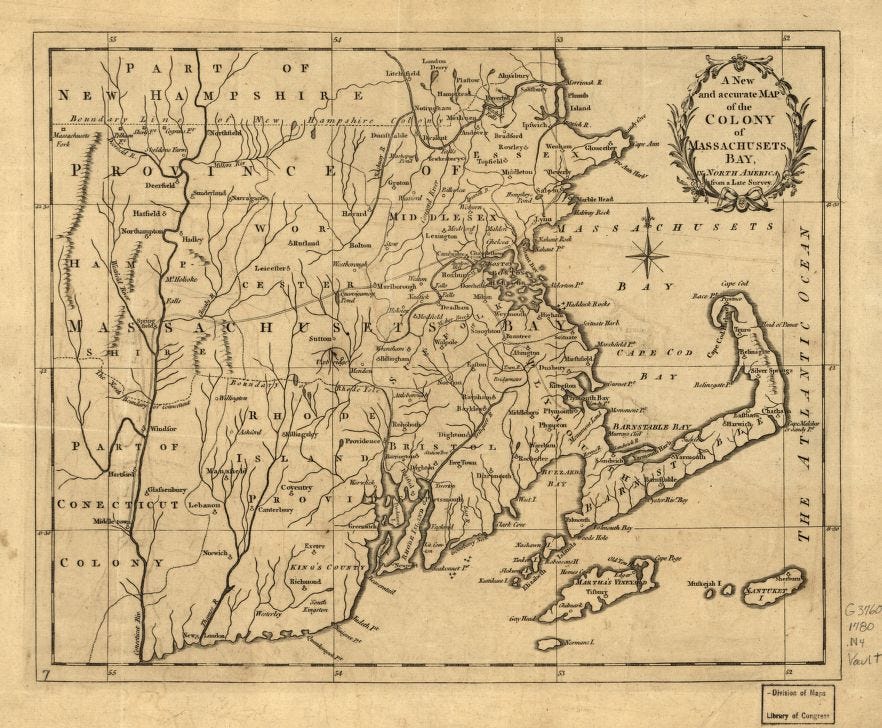

1. Myth: The 1692 witch trials only happened in Salem.

Fact: When the hysteria broke out, nearly every town around Salem Village – what is now Danvers – was involved. There were people accused in Topsfield, Boxford, Andover, Malden, Woburn, Ipswich, Amesbury, on and on, as far north as Maine.1

If this is your first time reading “Andover Bewitched,” this one might be news to you – or if you’ve been following along, I hope it’s not a surprise! For first-time readers, you can check out my introduction to the trials in Andover here.

2. Myth: Witch trials only happened in 1692.

Fact: People were accused of practicing witchcraft across Europe for centuries. There were accusations of witchcraft in the Americas as early as 1646 and as late as the nineteenth century.2

For example, in Andover, John Godfrey was accused of witchcraft in about 1665. You can read his story in full here. Godfrey was accused several times and was frequently in court, so many people around town did not like him and didn’t trust him. However, he managed to escape despite strong evidence against him and was pronounced “not guilty” during his trial.

The last people executed for witchcraft in the Massachusetts Bay Colony were hanged in September 1692.

3. Myth: Only women were accused of witchcraft.

Fact: Yes, more women than men were accused. However, about ¼ of the people accused were men – and their stories are part of the narrative of the witch trials too.3

Samuel Wardwell was an Andover man, accused and brought to trial for witchcraft. Wardwell was condemned to death for practicing witchcraft and hanged on September 22, 1692.

There are a few speculations about why more women than men were accused. This ratio is mostly consistent in Europe too, so it’s possible that the Puritans who began the accusations were already primed to accuse women instead of men. Other theories point to the social causes of accusations – men, fearing women with power, might have tried to accuse them to reclaim power… but women had more freedom in the seventeenth century than they did in later eras, so this doesn't add up.

4. Myth: Millions of people were executed for practicing witchcraft.

Fact: The trials in Europe and in the Americas were violent and frightening, and caused real harm on many communities. Experts estimate that the actual number of people executed for witchcraft is between 30,000 and 60,000 – and this is adjusted for possible lost records.4

During the 1692 trials, 20 people were executed (19 by hanging, and 1 man, Giles Corey, was pressed to death). Others, like Andover’s Ann Foster, died in jail awaiting trial.

5. Myth: People were burned at the stake in the Americas for witchcraft.

Fact: While burning was a common mode of execution in Europe, it was not practiced during the 1692 trials. Because this was carried out through the Massachusetts Bay Colony court system, all those sentenced to death during 1692 were hanged – this was considered an appropriate mode of execution for the death sentence.5

6. Myth: “Witchcraft” only meant practicing magic.

Fact: When we think of “witchcraft” today, we might imagine magic and potions, or other forms of magical practice. It’s true that seventeenth-century people understood that there were supernatural aspects of “witchcraft,” but the accusation was more about making deals with the Devil than doing magic.

Take Sarah Bridges’ account as an example. After initially denying the charges of witchcraft, she admitted:

“She had been in the Devil’s snare ever since the last winter, and that the Devil came to her like a man… [He] would have her sign his book, and told [her] his name was Jesus and that she must serve and worship him.”6

We can see here that Sarah — and her accusers — were thinking about the crime in association with the Devil and religious practice, not magic like we might think of today.

7. Myth: The church was behind all accusations of witchcraft.

Fact: While the church and the legal system were closely intertwined, the church wasn’t in charge of the witch trials… and many of the accusers were not directly involved with the church’s administration. Instead, the trials took place on the legal side and involved disputes between neighbors, not between individuals and the church.

Plus, the legal system was set up to allow for accusations of witchcraft. Because many seventeenth-century people believed witchcraft could cause genuine harm to other people, and because witchcraft meant making a deal with the Devil, it was considered a capital crime. That put “witchcraft” on par with murder or infanticide; other less severe seventeenth century crimes included theft and slander.7

8. Myth: Anyone who was accused of witchcraft was automatically found guilty.

Fact: Only a small percentage of those accused of witchcraft were actually convicted! In fact, most people who were accused and even arrested were pronounced “not guilty.” Though hundreds of people were accused of witchcraft during the 1692 trials, only twenty were executed.

Today, when someone is accused of a crime, our courts function under the assumption of “innocent until proven guilty.” When an accused witch took the stand, the courts assumed they were guilty.8 It was safer for an accused witch to “confess” to their crimes (even if they didn’t commit them) because the courts assumed their guilt – and saw a denial as evidence that they were still under the Devil’s sway.

9. Myth: People in the seventeenth century didn’t understand the harm the trials caused.

Fact: Even during the trials, members of Andover and neighboring towns spoke out against the trials. They were not only defending their own lives – they were also arguing for a more fair legal system. One of the key changes made during and after the trials was the banning of “spectral evidence.”

Within twenty years of the trials, the governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony cleared the names of most of those accused.9 Governor Phips also issued a law that granted restitution to those accused and their families, returning lost wages, jail fees, and compensation for those who were executed.

Others, like Samuel Sewall, who served as one of the judges, issued public apologies for their involvement in the trials.10

Though our modern eye allows us to be even more critical of this period, many people who lived through the trials understood the harm and spoke out against it, even as the trials were ongoing.

What do you think? Are there any other myths you’ve learned — or wondered — about life in 1692?

Thank you for reading, and as always: stay tuned for more entries of Andover Bewitched!

Plus, click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

— Toni

Check out a few other New England examples: Gordon Harris, “Lucretia Brown and the last witchcraft trial in America, May 14, 1878” Historic Ipswitch. Chris Pagliuco, “Connecticut’s Witch Trials” Wethersfield Historical Society. And Jessica Traynor, “Irishwoman Ann Glover, the last woman hanged for witchcraft in Boston,” The Irish Times.

See John Demos, Entertaining Satan - Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England, (Oxford University Press, 1982). And check out this article for a conversation with Demos about gender and witch accusations: Donald A. Yerxa, "Witch-hunting in the Western World: An Interview with John Demos." Historically Speaking 10, no. 1 (2009): 35-36.

Brian P. Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (Pearson Longman, 2006).

“Witchcraft in Salem — Today in History,” Library of Congress. The act, “An Act to Reverse the Attainders of George Burroughs and Others For Witchcraft.” was made official in 1711, and later published in Boston in 1713.