A new look at Lucy Foster, her life, work, homeplace, and community, part 1

In honor of Black History Month, today we share part 1 of the story of Lucy Foster. Born into slavery in 1767, Lucy lived her later years as a free woman, living in her own home, on her own property.

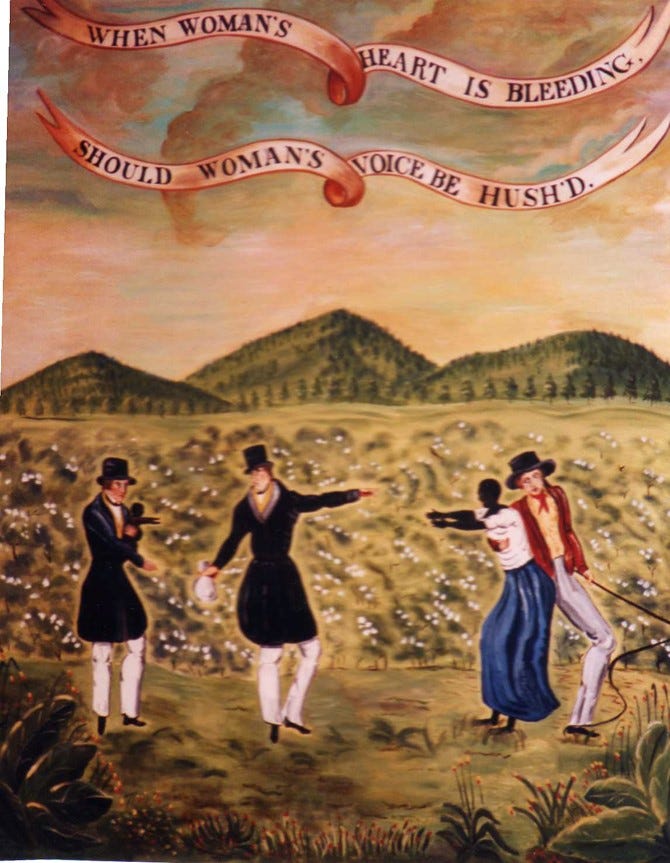

In 2019, students from the Academy at Penguin Hall brought together scholars and artists to create and install a memorial to Lucy Foster in the South Church Burial Ground on Central Street in Andover.1

Who was Lucy Foster?

For many, many years, Andover resident Lucy Foster was viewed through a single, narrow lens. However, recent research, writing, and interpretation has expanded the lens to tell a fuller, richer history of Lucy Foster and her role in her community.

Earlier research and interpretation of Lucy Foster solely as an enslaved African provided,

A window…into Lucy as (a) domestic servant, not really as Lucy was in her own homeplace interacting with the Black community around her.2

Lucy Foster’s story begins long before her birth in Boston, Massachusetts in 1767. Slavery existed in Massachusetts since the earliest days of the colonies. Officially, the first Africans arrived in Massachusetts in 1638, however, there is evidence of earlier arrival.3

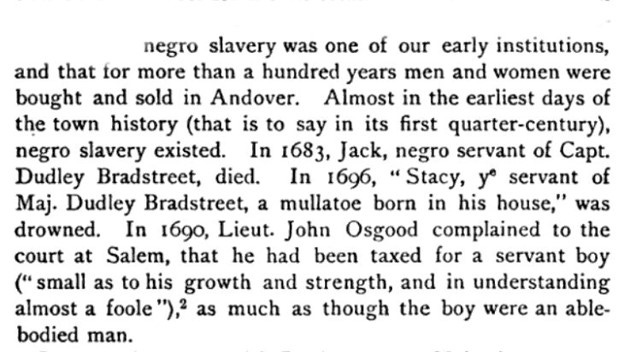

We don’t know when exactly when the first enslaved Africans were brought to Andover, which was founded in 1646. One source, Sarah Loring Bailey’s 1880 book Historical Sketches of Andover, tells about the 1683 death of “Jack,” a “negro servant of Captain Dudley Bradstreet.”4

Slavery in New England

African Americans weren’t a large part of the New England population in the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries. The 1790 census lists 5,400 African Americans living in Massachusetts, 1.4% of the total population. “The number of Black people in White households was at its peak in 1790 and decreased steadily throughout most of the first half of the 1 9th century.” By the 1840 census, the African American population rose to 8,660, still only 1.2% of the population.5

In the 17th century, New England Puritans tried to balance their Christian beliefs with their slave-holding practices. Some believed that non-Whites were not human and therefore had no soul to save, so conversion and baptism were not important, or possible. Biblical references to slavery legitimized the practice for many New England enslavers.

Others, such as Cotton Mather, argued that since all men were created by God, they must have a soul and therefore should be baptized and become members of the church. He believed that all men were worthy of God’s grace. However, he also wrote that godly salvation was not the same as earthly freedom.6

Apart from religion, by English law, a Christian could not own another Christian, which created its own unique problem: it became a reason to not Christianize enslaved people, as it would lead to a loss of property. In 1711, Connecticut passed a law that enslavers could not free and abandon the sick or elderly to avoid the expense of maintaining them. Of course, part of the concern was more self-serving because if the slaveholder didn’t bear the cost of caring for the person, the town would be obligated to.

Africans in Andover

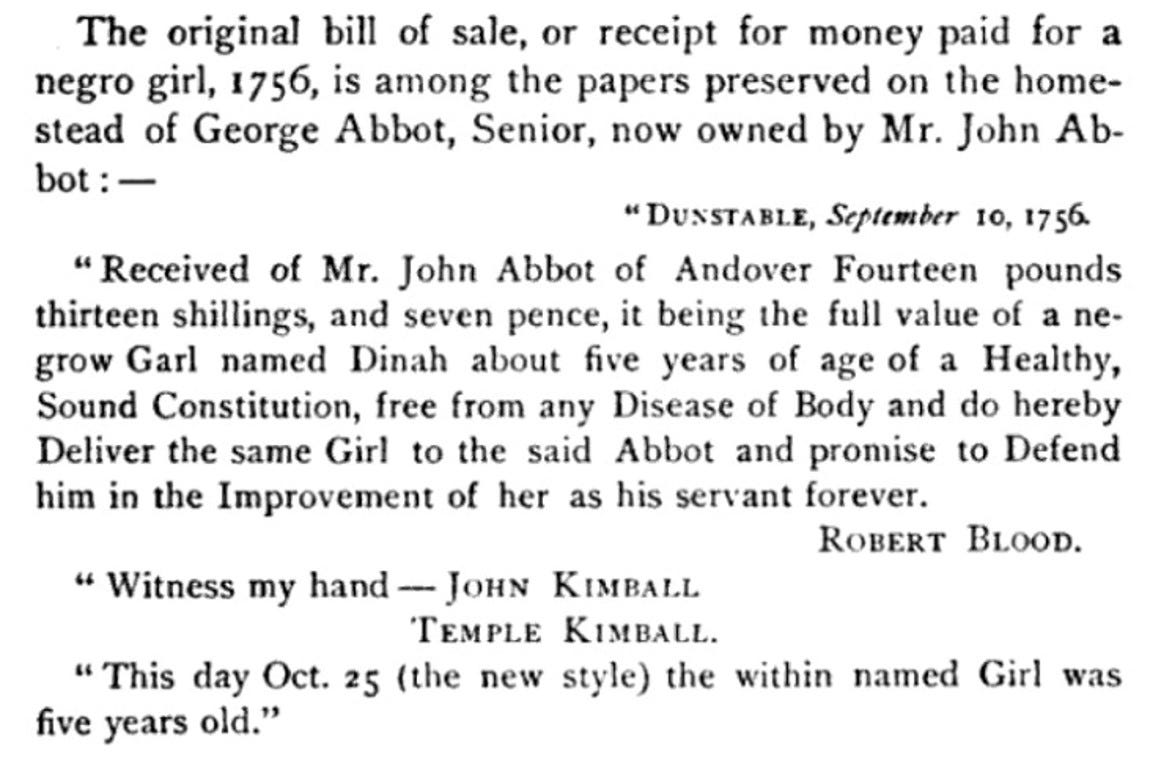

The African American population in Andover wasn’t counted until the first census in 1790, prior to that we only have anecdotal evidence, again from Sarah Loring Bailey. Bailey wrote about Stacy, “a mulatto slave of Major Dudley Bradstreet, who was born in his house and was found drown in 1696.” About that time, Lt John Osgood filed a complaint about paying taxes on a servant boy. Bailey also wrote about Dinah, who in 1756 at the age of five, was sold away from her family in Dunstable to John Abbot of Andover for 14 pounds. Records indicate that slaveholdings in Andover were small, with most families holding one or two enslaved people.7

In Andover, as elsewhere in New England, enslaved and free people lived and worked together. Enslaved people did not have separate living spaces as they eventually had in the south. They worked alongside whites in the fields and in the household and adopted their customs and beliefs, but were never considered to be fully equal even after slavery was abolished by judicial decree in Massachusetts in 1783.8

Attitudes toward slavery in New England

Since Massachusetts abolition in 1783 and the growing anti-slavery movement that started in the 1830s, New Englanders felt they could look back with pride at what was considered the “relatively mild” treatment of the enslaved population. However, the fact remains that northern enslavers could and did buy, sell, and deny basic human rights to other human beings, the same as southern enslavers.

This 19th century perception of “benevolent New England slavery” was often paired with a nostalgic and paternalistic affection for formerly enslaved people. This was expressed as “the feeling of an adult for a childlike and dependent” person “who could not be conceived as every outgrowing his dependency.” That some people chose – or had little choice but to – stay with their former enslavers, was seen as another sign of benevolence.9

Lucy Foster

This background leads us to the Andover story of Lucy Foster. Lucy was born into slavery in Boston in 1767 and in 1771 at the age of four was separated from her family and community and given to Hannah Foster, the wife of Job Foster, a well-to-do farmer in Andover.

When Lucy was baptized into the church that year, she was given the name Foster.

What kind of work would a 4-year-old enslaved child do? If we look at attitudes toward children in the 18th century, it would appear that Lucy would have been a fully functioning member of the household. Children were seen as little versions of adults, clothed like adults, expected to behave as adults, and participate in the work of the house. “Childhood” as we know it, was a 19th century adaptation made possible by the Industrial Revolution.

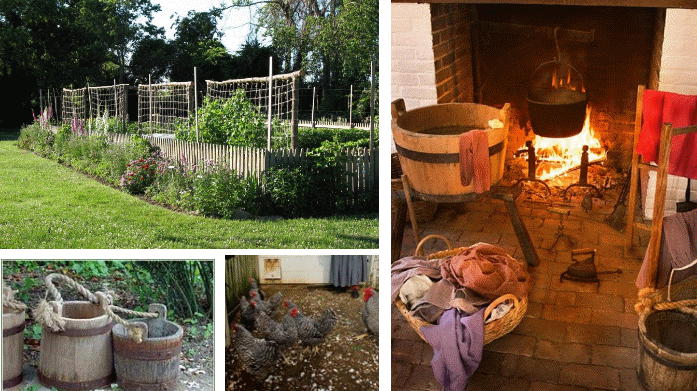

Young Lucy would likely have worked alongside Mrs. Foster or another servant on food preparation, cooking, cleaning, laundry, clothing production, and management of the kitchen garden and any small livestock or poultry they may have kept. At age four, we can imagine Lucy collecting eggs, weeding the garden, harvesting vegetables, spreading linens to dry, and stirring cooking pots. As she grew older, she would have taken on more responsibility for these tasks, taking on heavier chores such as laundry and ironing.

Lucy remained with Hannah Foster even after the Massachusetts Emancipation Proclamation was passed by judicial decree in 1783. In 1782, the year before emancipation, when Lucy was just 16 years old, Hannah’s husband Job Foster died. Although emancipated by law the next year, Lucy stayed on with Hannah until she was 22 years old.

Is this an example of the storied New England benevolence and affection between former enslaver and a formerly enslaved person? Where would an unattached 16-year-old female go in the 1780s? Perhaps staying with Hannah was based on affection, perhaps it was two unattached women staying together for mutual companionship and help. More than likely, it was Lucy’s only option.

Then in 1789, after 18 years together, Lucy left the household after Hannah married her next husband, Philomen Chandler. We don’t know why, and it raises more questions. Did the Chandlers already have enough servants? Was there a conflict with someone in the Chandler household? Or at 22 did Lucy want to strike out on her own? What was her place in the African American community in Andover?

What was Lucy Foster’s life like as a recently freed person of color in Andover? We don’t know where she lived or how she supported herself. She most likely hired herself out as a domestic to other families in town.

Warning Out

We know that in 1791 she was “warned out” of town for failing to obtain proper consent to live here. “Warning out” had a long history in Massachusetts. As Josiah Benton noted in his book, Warning out in New England, warning out was a community insurance policy of sorts.

The effect of warning out as thus practiced upon persons who remained in the town after being warned was to relieve the town from all obligation to aid them if they became poor and in need of help or support. They were inhabitants of the town for all purposes except being helped if they needed help. They paid taxes, they could vote, they could hold office they could perform all the duties of citizenship and of taxpayers, and yet if they had been warned out they could have no help from the town. They might be taxed for the support of others who were in need, but when they came to be in need they were entitled to no help from the taxes of the town. They were spoken of among their neighbors as persons who had been warned. 10

By the standards of the time, a 22-year-old old unattached free formerly enslaved woman would likely have been seen as a liability to a small community that was obligated to take care of her if she needed help. By warning Lucy out, the town freed itself from that obligation, but Lucy was free to continue to live in Andover.

Lucy remained a member of the church throughout her life, so there is evidence that she did stay in town. In 1793, Lucy’s son Peter was baptized in the church. We don’t know when Peter was born. Could he have been a reason to warn Lucy out of town?

What was the black community in Andover like, and what was Lucy’s place in it?

The black community in Andover was shrinking throughout Lucy’s lifetime. Young people might have moved away seeking opportunities. Older people stayed and aged where they had lived probably most of their lives.

In 1790, eight years after emancipation, the census counted 93 people of color living in Andover. By the 1840 census, only 26 remained. Among those 26 were Cato Freeman, Rose Coburn, Barzillia Lew, and Lucy Foster.

By the 1860 census no people of color living are recorded as living in Andover. The town split into Andover and North Andover in 1855, and Anthony Martin points out that in 1860 the black population lived in what was then the newly named town of North Andover.11

Lucy’s life took another turn in 1800 when, at age 33, she, along 7-year-old Peter, returned to Hannah Foster Chandler’s home following the death of Philomen Chandler.

In the 1800 and 1810 U.S. Censuses the widow Hannah Chandler is listed as living with two other free persons of color. One of them is likely to be Lucy Foster. The other could have been Lucy’s son, Peter. Peter would have been around 10 years of age in 1800 and 20 in 1810.12

Lucy stayed with Hannah for 12 more years until Hannah’s death on Christmas day in 1812. In her will, Hannah bequeathed “to Lucy Foster, the Black Girl, who lives with me, 1 cow, 1 acre of land……to have and to hold the same to the said Lucy for and during her natural life.” Hannah also bequeathed to Lucy $126.15.

And so, at the end of part 1, we’ll leave Lucy Foster on the verge of a new chapter in her life. She lived the first 16 years of her life enslaved, another nearly 30 years living, perhaps, in white family’s homes as a servant, and finally at age 45 a property owner.

In part 2, we’ll share more about Lucy’s homestead and explore new research into Lucy Foster’s life in her own community.

Thanks so much for reading. Please like, share, and leave comments.

~Elaine

Anthony Martin, “Homeplace Is also Workplace: Another Look at Lucy Foster in Andover, Massachusetts,” Society for Historical Archaeology, February 28, 2017, published online January 18, 2018, p. 107

Martin, p. 101

Sarah Loring Bailey, Historical of Andover (comprising the Present Towns of North Andover and Andover), Massachusetts, Houghton Mifflin, 1880, page 39

Martin, p. 102

Bailey, p. 39.

Roger N. Parks, Blacks in New England, 1973 and 1978, in the research files of the Andover Center for History and Culture, p. 4

Josiah Benton, Warning Out in New England, W.B. Clark Company, Boston, 1911, p. 116 https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001261678

Martin, p. 102

According to Anthony Martin, the Andover Vital Records lists the death of “Peter,” no last name, in January 1807. There’s no way of knowing if that was Peter. Martin, p. 103

As a Black resident of Andover since 1981, your article was "Wonderful"..Maybe you could do an article on twentieth century African American's in Andover.. Carl Byers was on the Finance Committe and helped get affordable housing for Andover citizens..Red Sock captain and Hall of fame inductee Jim Rice is an Andover resident.. My husband, Elmer (Al ) Kountze was District Manager for the telephone company in the Merrimac Valley area in the 80's and 90's..I am a member of the Andover Democratic Town Committee and I've been an election poll worker for years. I'm sure there are other stories!!

Hi Elaine -- love this. Any evidence that Lucy ran a tavern? The Chandlers and many of their relatives ran taverns -- and women made the beer as it was women trade. Seems would be a good trade for her to make money.

I also wonder about the 1% number -- as we have Lucy and her son, Pomp, Salem Poor and his wife and others -- these alone begin to go over the 1% number in Andover in the mid-1700's