A new look at Lucy Foster, her life, work, homeplace, and community, part 2

In honor of Black History Month, today we share part 2 of the story of Lucy Foster. Born into slavery in 1767, Lucy lived her later years as a free woman, living in her own home, on her own property.

In the years following Massachusetts’ abolition of slavery in 1783, historian Anthony Martin writes, “many women of color were trapped in the same relationships with White families they had had during captivity.” Some, like Lucy Foster, Martin wrote, were able to break free from that trap and establish their own “homeplace” where they could live and work in their own community.1 You can read part 1 of Lucy Foster’s story here.

Finding Lucy’s homeplace

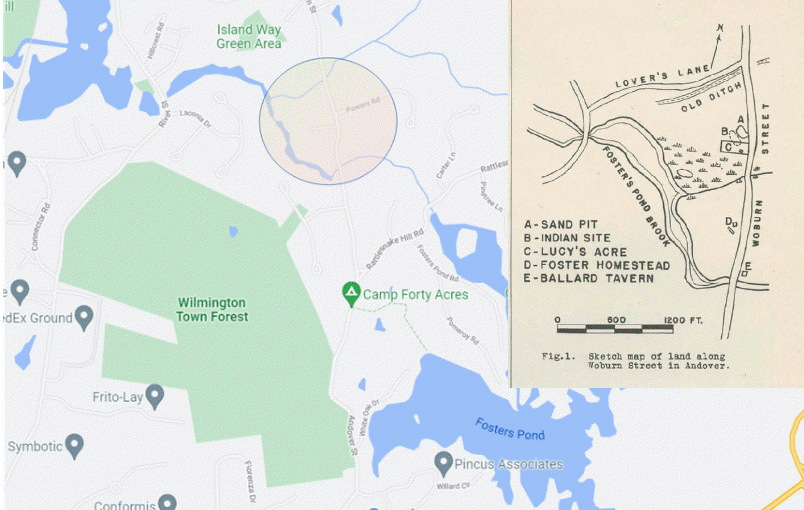

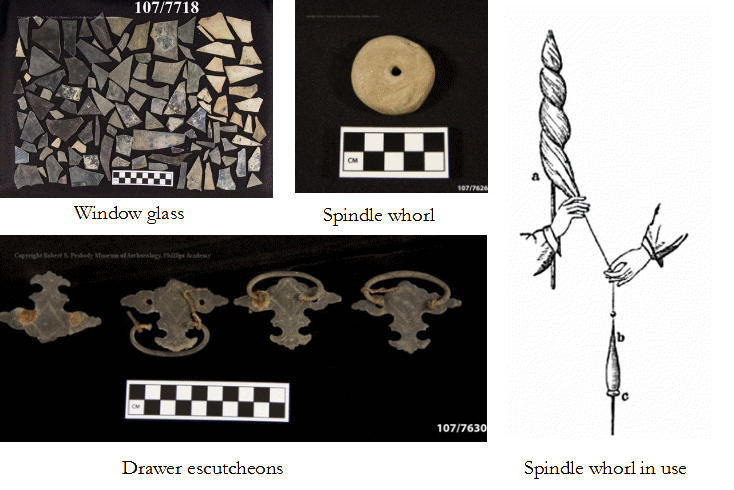

In the early 1940s, archaeologists Adelaide and Ripley Bullen conducted an archaeological dig on the site of Lucy’s cottage. In 1945, they published their findings in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeology Society. Artifacts from the dig site are in the collection of the Peabody Institute of Archaeology on the Phillips Academy campus.

The archaeological dig is notable because it was first study to focus primarily on the African American history of a site. Prior to their dig, finding African American related materials was coincidental to the initial focus of archaeological digs.

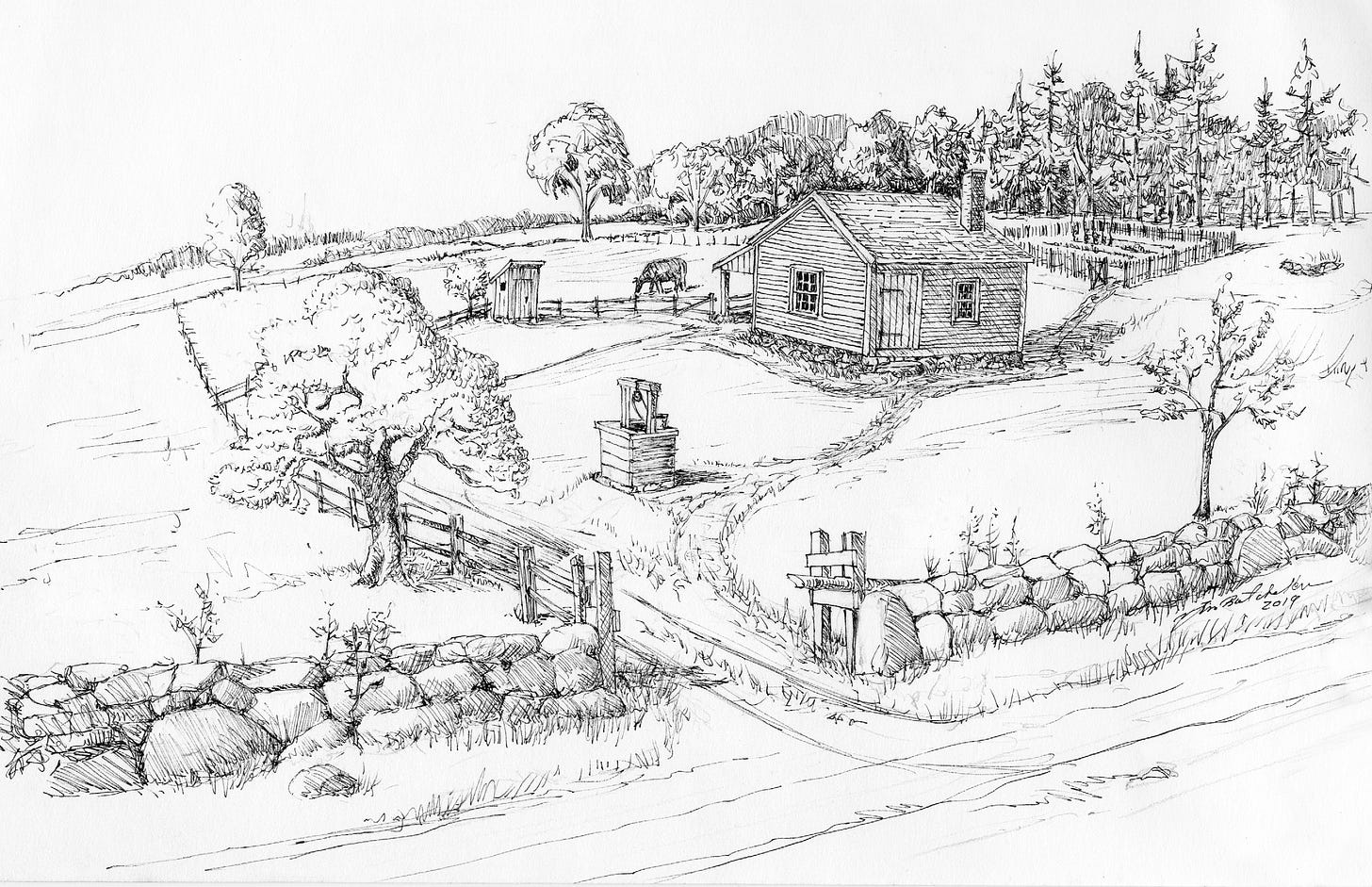

In their report the Bullens wrote, “While we cannot be sure as to exactly when Lucy’s cottage was built, it could not have been before 1813. Joshua Ballard as executor had a moral obligation to see Lucy installed. Alfred Poor says, “Capt. Joshua Ballard with $150 of her own (Lucy’s) money, together with some more contributed by her friends, built her cottage about 1815.”

In his writings,2 Anthony Martin places Lucy in the Black community, using the artifacts found on the site to give shape to Lucy’s everyday life as an independent free woman of color in the early 19th century.

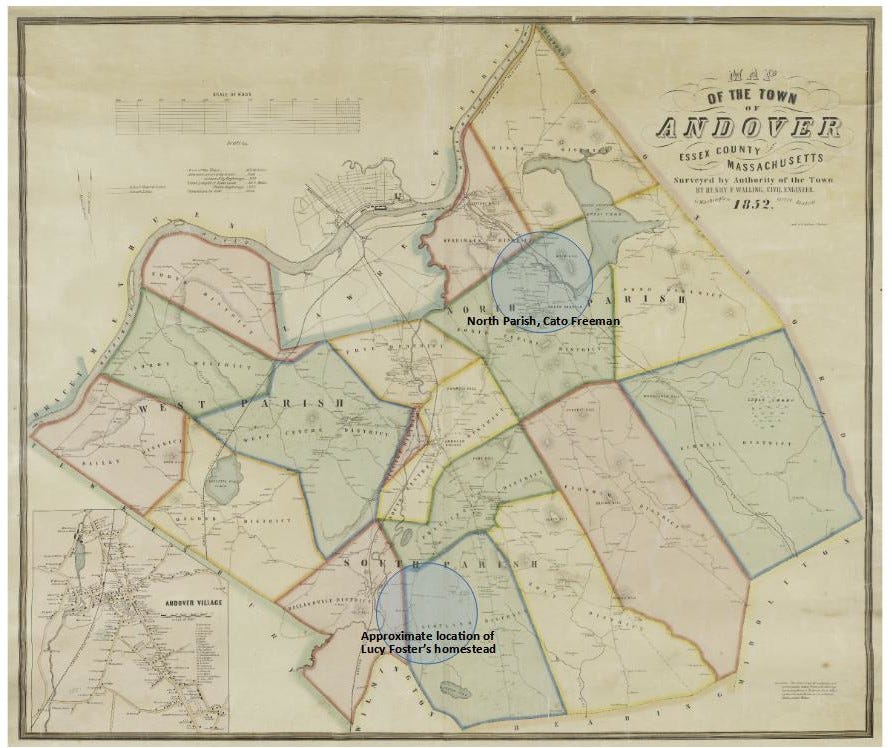

Martin described a community of people of color living within walking distance of each other.

Three other women of color lived near Lucy Foster: Flora Chandler and two others, unnamed in the census. The abundance of ceramics and kitchen related artifacts uncovered on the site – 113 in all – raises many questions. How did Lucy acquire so many pieces? How did she use them? Perhaps, as has been recorded in other communities, she used her yard as an outdoor tavern in good weather.3

Perhaps Lucy’s home and yard were a community gathering place.

Did Lucy live alone in her house? The only evidence the Bullens found was a story by Miss Ethel Howell, whose mother was born on the Foster Farm. Miss Howell was told by her great aunt that a “negro couple” used to live there. That’s not much to go on, but could indicate that her son Peter lived with her at least some of the time.4

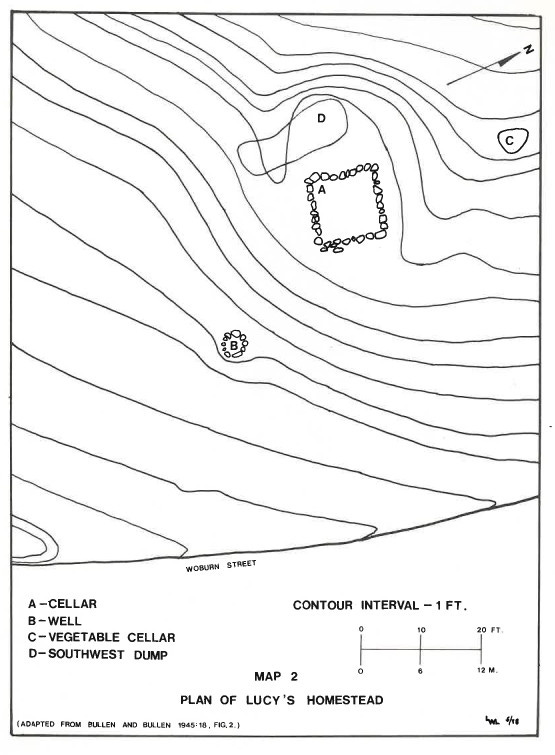

The Bullens’ dig focused on five areas: cellar hole, dump, well, vegetable garden, and what is described as a lumberman’s shack on the property.

The dig revealed that Lucy’s house had a stone foundation and sand and brick floors. A few fragments of window glass hint at glass windows. A chest of drawers was suggested by a set of seven escutcheons with pulls and a key hole. Lucy’s work was suggested by other items found: a brass key, containers, gunflints, grindstone, a hoe and shovel, a rifle ramrod, and a spindle whorl that provided weight when spinning. “It is important to note,” Martin wrote, “this is not Lucy’s entire assemblage, but what was actually recovered.”5

Materials from the dig are on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

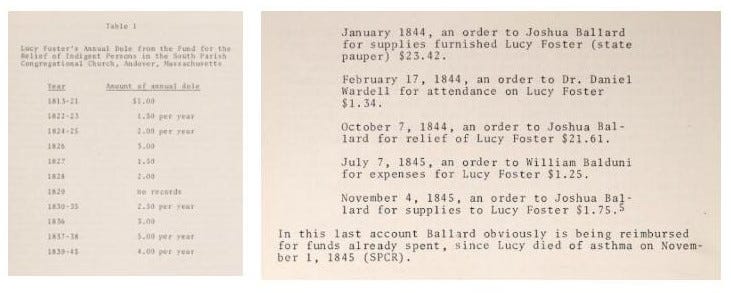

Lucy lived in her homestead for 30 years, from 1815 until 1845, between the ages of 48 and 78. Although some researchers conclude that Lucy was “economically impoverished” in her later years, local historian Joan Patrakis has argued that, “although she received public assistance for the remainder of her life, she was hardly a (financial) burden” to the community.

The Church gave her some small support: $1.00 to $5.00 a year from church funds. And, in the last two years of her life, the Town Treasurer’s and Overseer’s Records show that wood and supplies were delivered periodically when the weather was bad . . . small assistance for a single woman in her 70s.

Lucy lived independently until October 22, 1845 when, at 78, she was admitted to Andover’s Alms House, ten days before she passed away, on November 1. Asthma was the recorded cause of death, but it could have been any lung-related illness such as pneumonia.

The study of history and the interpretation of existing documentation changes over time. What the Bullens concluded in 1945 is different from Anthony Martin’s conclusions today. The Bullens looked at Lucy through the lens of the white majority population, and how they might have perceived her.

Anthony Martin looks at Lucy and her life through the lens of the Black population living in a racialized society. Martin questions previous conclusions about the Black community in Andover and their relationships, concepts of poverty and wealth, labor, freedom and enfranchisement.

Lucy’s homeplace was on or near the main road to Boston, so it might have been a gathering place for travelers. Professor Whitney Battles-Baptiste has proposed that Lucy might have been a participant in the Underground Railroad.6

Lucy lived in a community that included Pompey and Rose Lovejoy, Cesar Dole and his family. She was just 3.5 miles away from Cato Freeman. Martin posits that she would have had many opportunities to gather with her community after segregated church services, for funerals and celebrations, and for Black holidays.

Holidays such as Abolition of the Slave Trade, West Indian Emancipation Day, and Crispus Attucks Day were celebrated in the nearby cities of Danvers, Salem, and Boston. If Andover residents were unable to travel to these celebrations, Anthony Martin posits that Lucy Foster’s homeplace could have been a location to gather.

The written record reveals Lucy as a captive African, a mother, and a domestic servant. The archeological record reveals that she may also have worked to mend and make clothes, cook and serve travelers and neighbors. She also did the work needed to live: gardening, storing firewood, storing food, and clothing production and mending.

In his article, Martin wrote,

If she had lived to 1860, Lucy probably would have been listed (in the census) as ‘keeps house,’ However, she may have been doing the work of a hostler, laundress, caterer, tavern keeper, and maybe even seamstress.

Thanks to Anthony Martin’s work, and the work of other historians, we can begin to see Lucy Foster as the woman she might have been in her community.

In 2019, a new chapter to Lucy’s story was written over 250 years after her birth when students from the Academy at Penguin Hall brought together scholars and artists to create a memorial to Lucy Foster. The memorial is installed in the South Church Burial Ground on Central Street in Andover. You can learn more about the Burial Ground on the South Church website.

Thank you for reading. Please click on a link below to like, share, and leave comments.

~Elaine

Anthony Martin, “Homeplace Is also Workplace: Another Look at Lucy Foster in Andover, Massachusetts,” Society for Historical Archaeology, February 28, 2017, published online January 18, 2018, p. 101

Anthony Martin’s 2017 dissertation “On the Landscape for a Very Very Long Time” and “Homeplace Is also Workplace” (see footnote 1)

Whitney Battle-Baptiste, “Black Feminist Archaeology, Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Adelaide K. And Ripley P. Bullen, “Black Lucy’s Garden,” Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeology Society, 6(2), 1945, 17-28.

Martin, p. 107

Martin, p. 108