This is a Coffin Plate. We have several of them in our collection. But no coffins!

Coffin plates are small metal plates that were attached to coffins, identifying the name and death date of the deceased. Sometimes they tell more of a story.

The use of coffin plates has been around for centuries. This one, the coffin plate of King Edward VI, dates to 1553.

It was discovered in 1685, by workmen digging a burial place for King Charles II in Westminster Abbey and documented by Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Dean of Westminster Abbey. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour. The first of England’s monarchs raised as an Anglican Protestant.

Dean Stanley provided the inscription translation in his 1882 book, Historical Memorials of Westminster Abbey, “The Royal Vaults”

“Edward the sixth, by the grace of God King of England, France and Ireland, defender of the faith, and on Earth, under Christ, supreme head of the Church of England and Ireland, departed this life, sixth of July, in the evening at the hour of eight, in the year of our Lord 1553, and his reign of seven (years) his age sixteen.”

Coffin plates were generally made of lead, tin, pewter, copper, brass or silver. The small metal plates were affixed to the coffins for burial. Initially they were the mark of wealth or stature. Relatives who had the means hired skilled engravers to add inscriptions and images to their loved ones’ plates, in addition to the basic birth and death dates. Others went to the local blacksmith to provide a simple, and less expensive, coffin plate.

The use of coffin plates spread to the US in the early 1700’s. They were a popular local product of craftsmen including Boston silversmith, Paul Revere. By the mid-18th century, with the industrial revolution, more people could afford coffin plates. At first, in the 1840s, the machine-made plates were a simple design. Newspaper ads announced the availability.

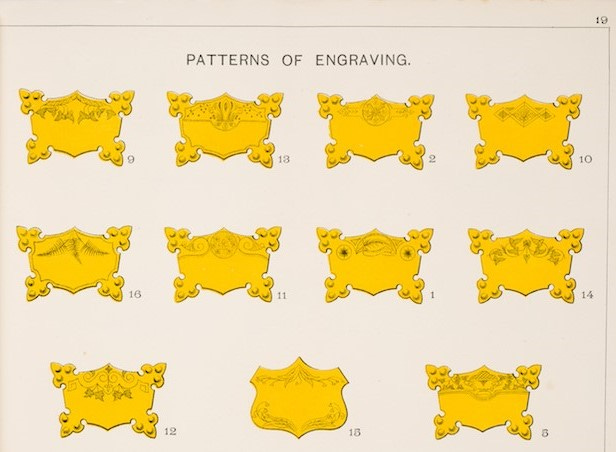

By the late 1850s- 1860s, there were more intricate designs. Manufacturers began stamping out blank coffin plates. Funeral homes, engravers, and jewelry stores would keep blanks in stock to have available for engraving upon purchase.

Trade catalogs like this one from the Newman Company in Birmingham, England advertised available styles and metals.

As coffin plates became more affordable, they became more popular. In England, coffin plates were required to be attached to the coffin at burial. In the United States, beginning in the early 1840s, coffin plates more often were not attached to the coffins. Instead they were displayed on the casket during the funeral and given to the family of the deceased as a memento.

This was a popular practice particularly in the northeastern states – Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

Having a deceased loved one’s coffin plate on display in one’s home or kept as a cherished memento, peaked in fashion in late 1880-1899. By the 1920s, the practice had died out.

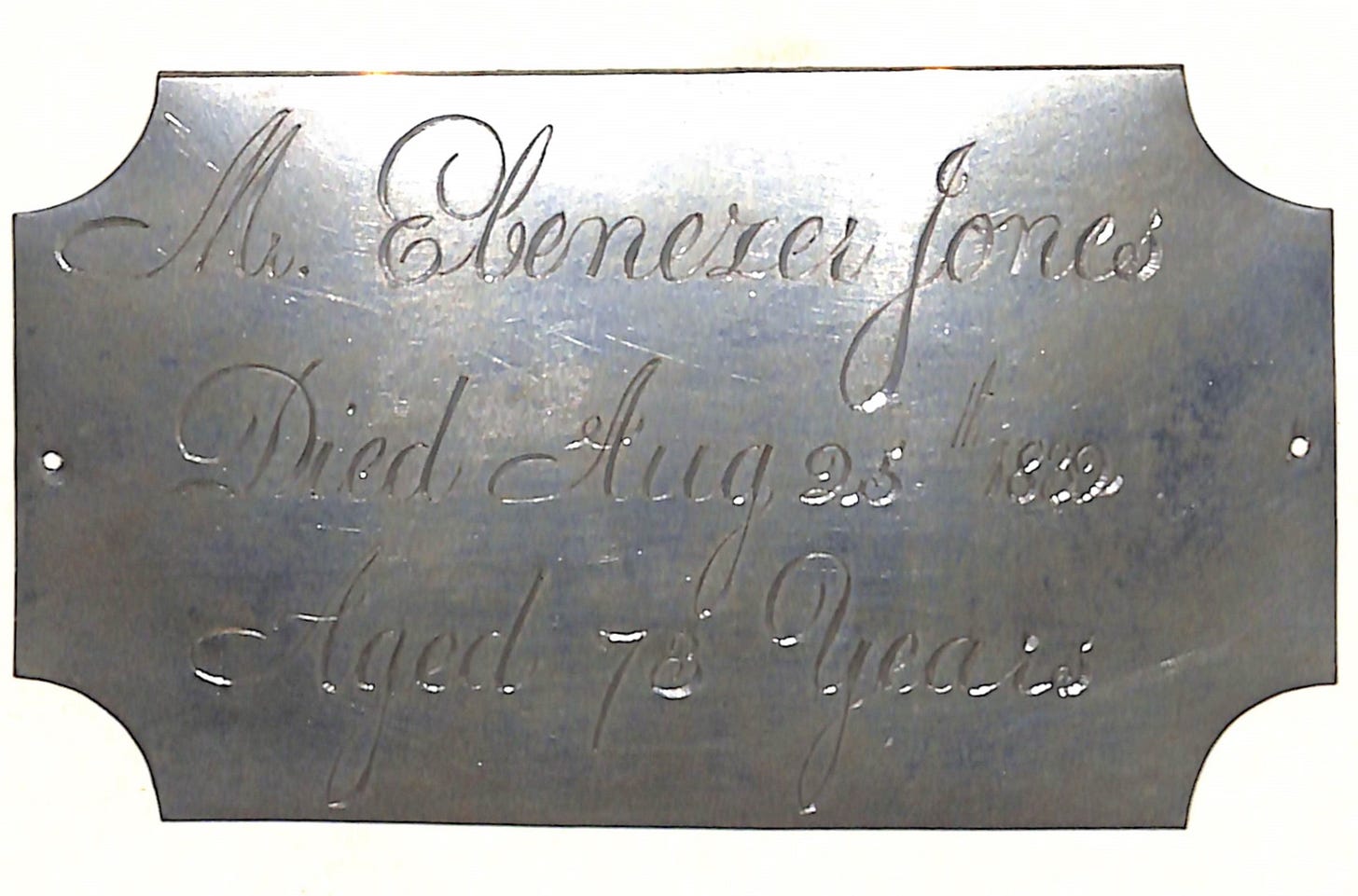

These coffin plates in our collection are from the Jones family of Andover.

These Coffin Plates provide a hint at the stories of those that were lost.

Dare I say…their spirits live on through their plates.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy these stories, please leave a comment or send me an email. I love hearing your stories and memories.

Thanks,

Marilyn Helmers

Mhelmers@andoverhistoryandculture.org

Postscript -

Breastplates were another type of coffin plate. More popular in Britain than in the U.S., breastplates were large -12 to 15 inches in height - and usually made of silver, copper or brass. Burials of royalty, and people of wealth or prominent position included elaborate breastplates on the coffins in addition to the simple coffin plates. The breastplates were attached to the coffin usually on the center top part, over the breast.

They were a part of the coffin and meant to be buried with it, never to be seen again. For an interesting saga of Oliver Cromwell’s breastplate, follow the story here.

Resources

Andover Center for History and Culture collection resources

Coffin Plates - Genealogy Resource