What's It Wednesday: Soap, Soap, Soap

It took more than a century for the concept that cleanliness stops the spread of germs to be adopted world-wide. It wasn’t until 1980 that the first U.S. National Hand Hygiene Guidelines were printed.

Remember when…

Two years ago the world changed with the rise of the coronavirus. Handwashing became the focus of our days. The CDC even gave us instructions on the most effective way to clean one’s hands – scrubbing with soap and warm water for 20 seconds – singing “Happy Birthday” twice as a timer – then rinsing and drying.

All this sounds like common sense and very routine to us now.

However, handwashing was not always advised. As a matter of fact, in the early 1800s it was deemed unnecessary and scandalous.

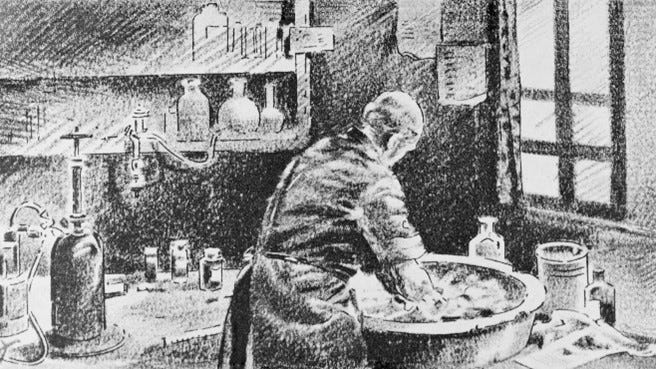

It wasn’t until the late 1800s that doctors in Europe and the U.S. adopted the practice of washing their hands prior to seeing patients. Thanks, in part to Ignaz Semmelweis. Semmelweis was a Hungarian doctor working in the Vienna General Hospital from 1844-1848. He advocated for handwashing.

Vienna General was a large teaching hospital with two separate maternity wards. One ward was for doctors and their students and the other one was for midwives and their students. Semmelweis noticed that the doctors’ ward had a greater rate of “childbed fever” (now known as streptococcal infections) than the midwives’ ward. Semmelweis also observed that doctors sometimes went from performing autopsies directly into the maternity ward. In 1847, he mandated that doctors wash their hands with chlorinated lime after each autopsy and before examining other patients.

The staff began sanitizing themselves and also their instruments The mortality rate in the doctors’ ward dropped significantly, to about the same level as the midwives’ ward rate. In 1850, Semmelweis delivered a paper at the Vienna Medical Society about the virtues of handwashing. His theory went against the accepted medical wisdom. Semmelweis was rejected by the medical community who felt that he accused the doctors of being directly responsible for the deaths of their patients. Despite the success in reversing the mortality rates in the maternity wards, the Vienna Hospital abandoned mandatory handwashing.

Semmelweis left Vienna and returned to Hungary. He continued to publish papers on the value of handwashing in restricting the spread of disease, but still his theories were not widely accepted.

Semmelweis wasn’t alone in his theory though. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., (1809-1894) physician, poet, professor, and inventor, wrote an article that was published in The New England Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Surgery in 1843, and then republished in 1855, Puerperal Fever as a Private Pestilence. The article supported the theory that childbed fever was a contagious infection that could be prevented with increased cleanliness. Nurse Florence Nightingale wrote in her 1860 publication, Notes on Nursing – “Every nurse ought to be careful to wash her hands very frequently during the day.”

In 1867, two years after Semmelweis’ death, Scottish surgeon Joseph Lister also championed the theory that sanitizing hands and surgical instruments might halt diseases. His ideas were criticized too, but in the 1870s physicians began regularly scrubbing up before surgery.

The work of Semmelweis led to Louis Pasteur’s development of germ theory, which changed the investigation of the cause and spread of disease and how doctors care for their patients.

Still, it took more than a century for the concept that cleanliness stops the spread of germs, to be adopted world-wide. It wasn’t until 1980 that the first U.S. National Hand Hygiene Guidelines were published.

Of course, soap itself has been around for thousands of years.

There is record of ancient Babylonians making soap. Archaeologists have found soap-like material in clay cylinders dating back to 2800 BC. The material was a mixture of animal fats and ashes. Papyrus documents from 1500 BC show that ancient Egyptians bathed and combined animal and vegetable fats with salts to make soap for washing. Ancient Roman legend has it that “soap” got its name from Mount Sapo in Italy. Rain washed down the mountain, mixed with animal fat and cooking ashes, forming a clay mixture that could be used for cleaning. By the first Century AD, soap was regularly being made from tallow and ashes.

By the 8th century, Italy, France, and Spain were centers of soap-making. Soap from these countries was deemed to be better quality as they refined soap-making by using olive oil, goat fat, and beech tree ash. Soap-making spread across Europe. By the 12th century, the English had soap-making guilds to regulate the quality of their soaps. Soap-making began in Colonial America in the 1600s, but it was mostly a household task until the late 1700s.

A major change to soap-making came about in 1791, when French chemist, Nicolas Leblanc invented a process for deriving soda ash from common salt. This simplified soap-making making the necessary ash ingredient readily available.

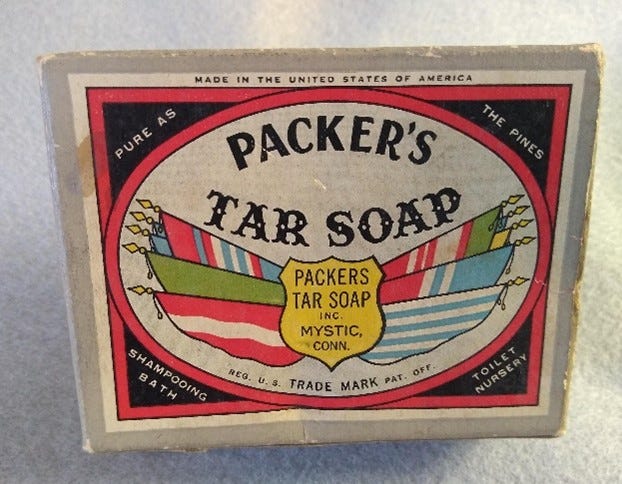

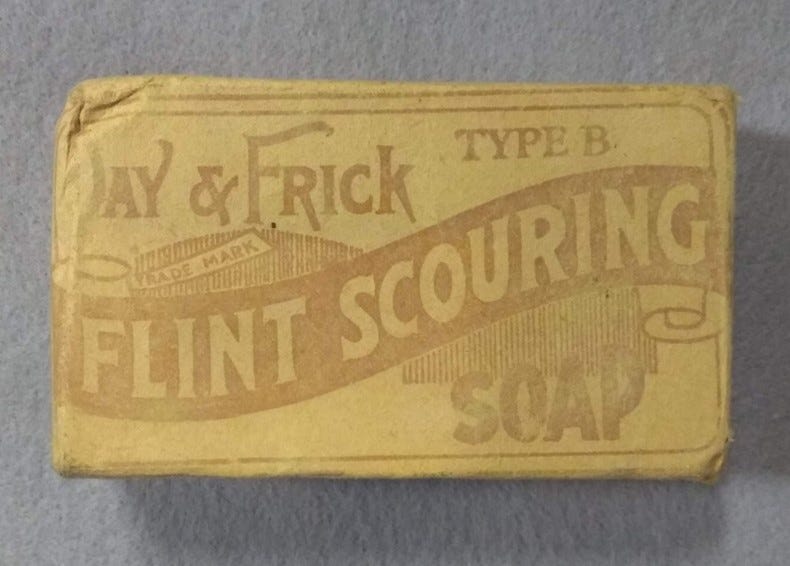

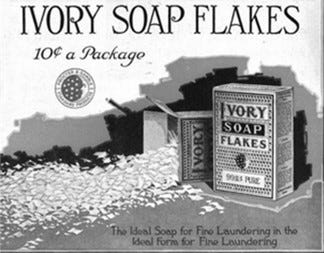

With the Industrial Revolution, the soap-making industry, especially in the U.S., took off. By the 1860s, many types of soap were being made for industrial purpose and general cleaning.

The basic formula for making soap hasn’t changed much over the years. It is a combination of fatty oil, an alkaline solution like lye or sodium hydroxide, and water. The type of oil or animal fat used affects the soap. Olive oil, palm or coconut oil makes softer and milder soap. Fragrances and color tints are added to toilet and beauty bars. In the case of industrial strength handwashing bars like Lava, volcanic pumice particles are added for extra scrubbing power.

Of course, pledges were made for each new soap to be “the best.”

With the 1920s, soaps had a bigger role than just being used for laundry or pots and pans. Toilet and beauty soaps were advertised as making skin soft and beautiful.

The 1930 U.S. Bureau of Standards listing for “procurement of material used by the Government” included 12 categories for types of soaps from over 500 companies. The types included: White floating soap, Liquid Soap, Soap Powder, Salt water soap, Automobile soap, Chip soap, Ordinary laundry soap, Grit cake soap, Powder, scouring (for floors), Milled toilet soap, Powder soap for laundry and Liquid soap, for laundry purposes.

Locally, Howard Pillsbury of Andover, MA made his own brand of hand cleaner.

Howard Everett Pillsbury lived in Andover from 1926 to 1938. He was the Chief Engineer at Andover’s Haggetts Pond water pumping station and master engineer at the American Woolen Mill. He must have known a bit about grimy hands. His hand cleaner promised “A Can Full of Satisfaction” and “Leaves Hands Nice and Soft.” It also pledged to provide “superior cleaning for all enamel work.” Unfortunately, we don’t know whether it lived up to the pledges. There isn’t much recorded about Pillsbury’s Hand Cleaner and the can is empty.

So, here we are – 2022. Two years later and we are managing to co-exist with coronavirus in all its incarnations. The fact remains, germs are everywhere. Take care and please, wash your hands!

Thank you for reading! Please share your comments, pictures, or memories. I’d love to hear your stories. Please comment below or email me at mhelmers@andoverhistoryandculture.org

Marilyn Helmers

Resources

Andover Center for History and Culture Collections

Hand-washing Disease Infection History

Encyclopedia.com - Nicolas Leblanc

Thanks Marilyn! I wonder what ideas we are resisting today that will become common sense in the future...