What's It Wednesday

New England winters are dark and gloomy. Imagine hundreds of years ago. What did people do? Maybe this will help shed some light.

Before there was electricity or kerosene lamps, there were candles.

Some method of lighting has been around for thousands of years. Reeds soaked in hot animal fat were used by ancient Egyptians as early as 3100 BCE. Beginning around 500 BCE, Romans made candles dipped in tallow, rendered from animal fat from cattle or sheep. The use of whale fat for candles dates to the Qin Dynasty in China 221-206 BCE. The Indigenous People of the Pacific northwestern North America used the oil from the eulachon fish (now known as a candlefish) to burn for light. When Colonial Americans arrived in New England they noted that the Indigenous People used dried pine branches to burn as torches. Pine torches were still used in northern New England as late as 1820.

Candles, as we know them, were used throughout Europe during the Middle Ages. Tallow candles were commonplace. Made from the hard fat of beef or sheep, the candles had a yellowish color. They also softened in hot weather, were sticky and greasy, burned with a smoky, sooty flame, and had an unpleasant smell.

Beeswax was also used during the Middle Ages. Beeswax has a higher melting point and so the candles weren’t as affected by hot weather. Beeswax or “wax” candles burned with a clear flame and no odor. But they were expensive. It took 60 pounds of honey to produce 1 pound of beeswax. Generally, wax candles were used primarily by royalty, the wealthy, and for religious ceremonies.

From the 1300s through the early 1800s, candles were made primarily by candle maker craftsmen known as “chandlers,” who made tallow dipped candles. The candle makers went from house to house making candles from the kitchen fats saved for that purpose, or made and sold their own candles from small candle shops. The first guild of chandlers, the Tallow Chandlers Company, was formed in 1300 in London. In 1462, King Edward IV granted the Tallow Chandlers a charter, giving them the authority to seize and destroy inferior tallow goods- candles, soaps, and other products. The organization still exists today.

In early colonial America, tallow candles were a rarity. It wasn’t until the 1660s that the colonies had enough cattle to supply the animal fat used for tallow. Prior to then, wax for candles came from the wild bees in the forest or from bayberries found growing in the coastal areas. Bayberries were easily picked and added a pleasant scent to candles, but it took many bayberries to produce enough wax. A bushel basket of berries yielded only 2-4 pounds of wax which would make about 6-8 candles.

Many cookbooks from the 1700s and1800s have recipes and directions for making candles at home. The American Frugal Housewife. Dedicated to those Who Are Not Ashamed of Economy by Mrs. Child (Lydia Maria Child 1802-1880), was published in Boston by Carter, Hendee and Co in 1833. Mrs. Child noted that:

Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s The American Woman’s Home: or, Principles of Domestic Science published 1869 in New York, had detailed directions on how To Make Candles, including instruction on making both molded and dipped candles. However, the authors felt that, “The nicest candles are those run in moulds.”

The process of dipping candles was a simple, but lengthy one. As described in Illumination in Colonial New England by Bob Grigg:

“The twisted or braided cotton or flax wicks were suspended from a stick called a candle rod, the number being determined by the size of the pot or kettle. When carefully straightened, the wicks were dipped into the melted tallow, receiving a coating of the hot fat. When cool, the operation was repeated until the candle had grown to the desired size. Some housewives first immersed the wick in a saltpeter. This made the wick burn more evenly and prevented what was known as “candle robbers,” which were simply the burning wicks bending over and coming into contact with the body of the candle, thus melting the edge and causing the reservoir of hot tallow to run down the outside of the candle and be lost.”

Once the candles were fully hardened, the wicks were slipped off the rods and the candles were ready for use.

The candles for immediate use were stored in a wooden or tin candle box which protected the candles from sunlight, which turned them yellow. The additional candles would be stored in cool cellars, wrapped, and placed in containers to protect the candles from being eaten by rats and mice.

During the early 1700s, large sheets of tin were being produced in England and from there exported to America. In the late 1700’s, colonists began producing their own tin and making household items. Tin, otherwise known as “poor man’s silver,” was an incredibly popular material since it was inexpensive, lightweight, and durable.

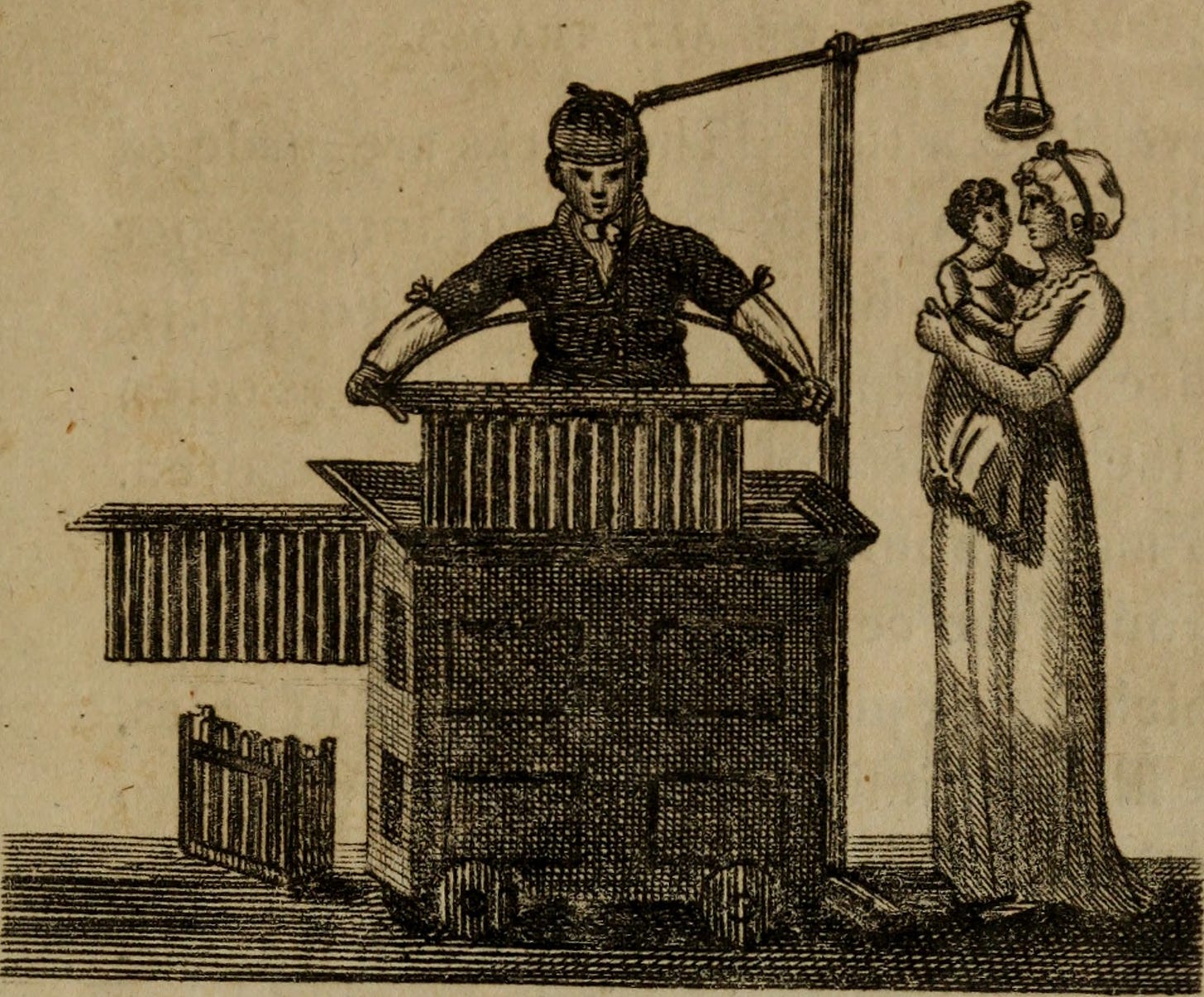

Some of those household products were candle molds. Candle molds were made by tinsmiths, often referred to as “whitesmiths” because they worked with hot, light-colored metals as opposed to blacksmiths who worked with cold, dark metals like steel and iron. The molds were usually made of tin or thin sheet iron. They consisted of slender, tapered tubes grouped together on a rectangular base, and a top with a small edge. A handle was secured to the side of the mold to make moving the mold easier. The top of the tubes are open. Most household-use molds allowed for 2, 4, or 6 candles to be made.

The wicks were inserted through the tubes and secured at the top and base. Melted wax was poured into each tube and then the mold was set aside to cool. After the candles hardened, the mold was dipped into water just hot enough to loosen the candles from the tubes. The candles could be lifted out by the wicks and rubbed smooth with a soft cloth.

Candle molds were incredibly labor saving. Although the wax or tallow still had to be prepared, compared to the dipping method, molding was much easier and less time-consuming for housewives. Molded candles had fewer imperfections, were straighter, and tended to burn longer than dipped candles.

Tin was also used for lanterns. Tin lanterns illuminated front porches and parlors throughout Europe as early as the 1500s. When the colonists arrived in New England, they ‘reinvented’ the square English lanterns that had glass or horn side panels. Sometimes referred to as ‘Paul Revere’ styled, pierced lanterns were prevalent in most colonial period homes and are on display in many historic homes today.

Pierced tin lanterns are round with a bottom that has a cup to hold a candlestick securely and a hinged door on the side. The top of the lantern is peaked with two vent holes. The peak ends in a ring that can be used as a handle or to hang on a peg inside a house or barn. The tin was punched with a nail or awl to emit light. Early, rustic lanterns often had random piercings. By the 1800s, the holes were arranged in more decorative patterns. In addition to emitting light, the piercings protected the candle flame from being blown out in a gust of wind. The lanterns could be carried from one place to another. By opening the door, more candlelight could be shed on a task.

The 19th century brought many advances in candle-making. In 1834, The first candle-making machine was invented by a British pewterer, Joseph Morgan. The machine used a cylinder with a moveable piston to eject the candles as they hardened. This continuous process produced about 1,500 candles per hour and made candles easily affordable. Industrialization and scientific discoveries of stearine and paraffin improved on the quality of candles. However, with the discovery of kerosene which could be burned in lamps, and the 1879 invention of the light bulb, the candle-making industry declined rapidly.

Candle-making had a resurgence in the 1980s, as a craft. Candles, of course are still used today in churches, temples, synagogues, for holiday celebrations and ceremonies, to light our dining tables, and when the power goes out. But they have had an increased therapeutic use in spas and massage centers and historically accurate candles are manufactured for the use in the film productions. The candle manufacturing industry is strong today. Recent industry reports for the U.S. market list a market size of $1.75 billion.

Thank you for reading! Please share your comments, pictures or memories of dipping candles, candle molds or pierced lanterns. I love to hear your stories. Please comment below or email me at mhelmers@andoverhistoryandculture.org

Check out these links to see candle making in action:

Video of Modern Day Candle Making

Resources

Andover Center for History and Culture Library and Collection

Candle Making Holliston Historical Society

I enjoyed reading about candles on a snowy day. Amazing that they've been around for so long in so many different forms! thanks.

So glad that you enjoyed it. Thanks.