What's It Wednesday - Money, Money and More

Look familiar? Guess what board game has this money. Look carefully though. You might be surprised by the answer.

It isn’t Monopoly money!

This is part of a very similar game unique to Andover, MA. The Game of Andover!

In September 1991, the Andover Townsman announced that:

“There is soon to be a new game in town.”

The Game of Andover was the brainchild of Andover’s Century 21 realtors. Century 21 was a corporate sponsor for Easter Seals, and they invited their local offices to raise funds for that cause. Andover’s Century 21 Minuteman office decided to sponsor a local version of the popular Monopoly game and sell it. Their goal was to raise $5000 by July of 1992.

The game was produced by

The similarities with Monopoly was no accident. But the changes to the board and iconic cards gave the game the hometown touch.

Instead of Boardwalk and Marvin Gardens, the 43 spaces on Andover’s game include local Andover businesses. The Andover Inn is in the spot where Boardwalk traditionally is. The Shawmut Bank got the coveted GO corner.

The game sold in advance for $15 each. The first 300 people, organizations, or businesses who ordered a game, had their names listed on the Patrons list along the center of the board. One such listing reads “President George Bush & Family.”

The game includes a game board, instructions, cards, money, dice and 6 colored plastic tokens.

There are over 300 different versions of the game of Monopoly and thousands of themed versions that have been custom-made for individual groups or fund-raising purposes. The Game of Andover has its place in the history of our town.

The game of Monopoly has a unique and checkered history of its own. Its roots go back to 1903 or earlier.

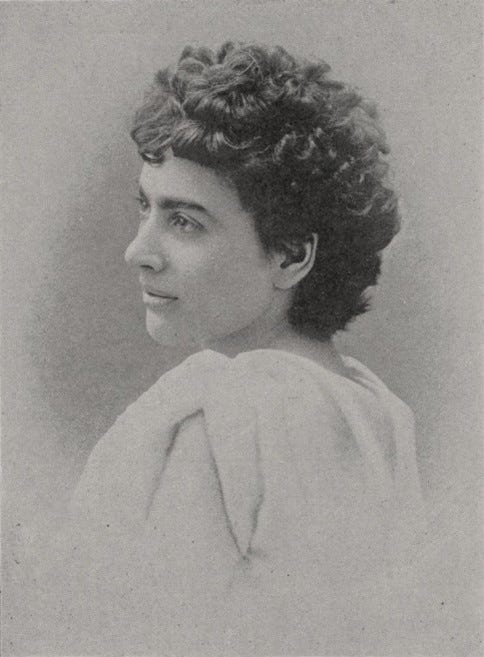

It was the product of a young woman determined to promote social and economic justice in the America of the late 1800’s. Enter Elizabeth “Lizzie” Magie and The Landlord’s Game.

Elizabeth Magie (1866-1948) had been introduced to the writings of Henry George 1839–1897, by her father. Henry George was an American economist and journalist whose writings and economic philosophy launched the Progressive Reform movement in the late 1880’s. Lizzie had read George’s book, Progress and Prosperity which put forth the theory that people should own the value they produce themselves, but that the economic value derived from natural resources, like land, should belong equally to all members of society. Henry George advocated Single Tax, where a tax on land values, not the buildings built on them, should replace all existing taxes. He felt that the result would stimulate construction and economic growth to the benefit of all citizens. He thought that a single tax would prevent the very wealthy from creating monopolies.

Lizzie was impressed by the economic concept of Henry George and decided to develop a way to teach others how George’s system of political economy would work in real life.

As a single woman living on her own outside Philadelphia, Lizzie was a frequent visitor to the Single Tax community of Arden, Delaware where she shared her game ideas with friends. She created two sets of rules: one, anti-monopolistic where all benefited when wealth was created. The second was the monopolist set where the goal was to amass monopolies and crush one’s opponents. She hoped to demonstrate that the anti-monopolist way was superior and more beneficial to mankind.

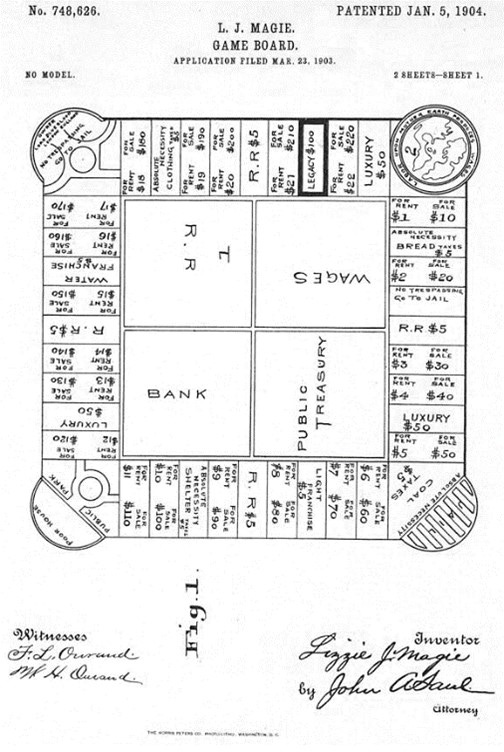

A few years later, Magie was working as a stenographer in D.C and living in Maryland. In the evenings, she continued to work on her board game idea and tested it with her friends. In 1904, she applied for and received a patent for The Landlord’s Game. In an issue of The Single Tax Review, Elizabeth Magie is quoted as describing her Landlord’s Game: “It is a practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences. It might well have been called the ‘Game of Life,” as it contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world, and the object is the same as the human race in general seems to have, i.e, the accumulation of wealth.”

In 1906, she formed a company with other proponents of Henry George’s economic theories. That company, The Economic Game Company of New York, published The Landlord’s Game.

The game’s purpose of social critique was apparent enough that university professors began to use it in their teachings and students borrowed the idea to build their own games.

Between 1910 and the 1920’s many versions of the game appeared. It was popular on college campuses including the Wharton School of Finance and Economy, Harvard, and Columbia. Players drew game boards on oil cloth or paper and created their own customized board games modeled on Elizabeth Magie Phillips’ concept. (Lizzie had married Albert Phillips in 1910.)

In 1932, Elizabeth Magie Phillips’ second edition of The Landlord’s Game was published by the Adgame Company of Washington D.C. Unlike the initial game, the 1932 edition had two different setups. In one, the goal was to own businesses, create monopolies, and win the game by forcing other players into bankruptcy. This was known as the “Monopoly” version and became very popular. The alternate was the anti-monopoly setup or “Prosperity” version. The goal of this version was to create new products and build wealth through cooperation and interaction with opponents.

At this point in time, history becomes a little murky. Enter Charles Darrow.

One evening, also in 1932, a Philadelphia businessman, Charles Todd and his wife Olive, invited Charles Darrow, an engineer friend, and his wife Esther to play a new real-estate board game. The game involved rolling dice, moving tokens around a hand-drawn board, and buying up properties. At the end of the evening, Charles Darrow asked Todd to write out the instructions so that Darrow could play with friends at home. The game wasn’t sold in a box and didn’t have a formal name, but the rules were passed from friend to friend. It became referred to as “the monopoly game.”

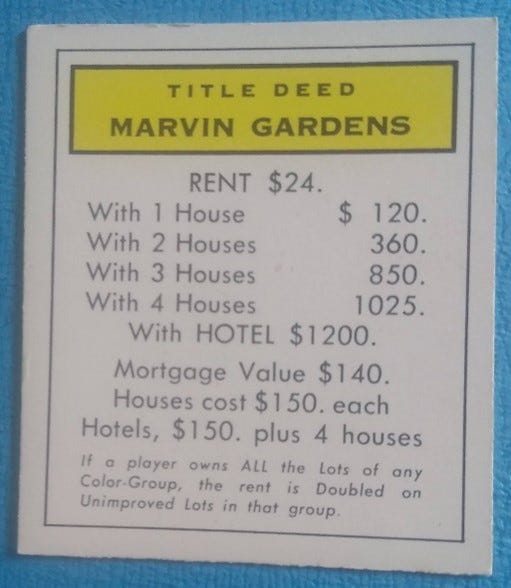

Charles Todd wrote out the instructions for Darrow but accidently misspelled one property name – Marvin Gardens, instead of Marven Gardens, a village in Atlantic City, New Jersey. (The Todd’s version of the game had been set in Atlantic City.) The “misspelling” has stuck to this day.

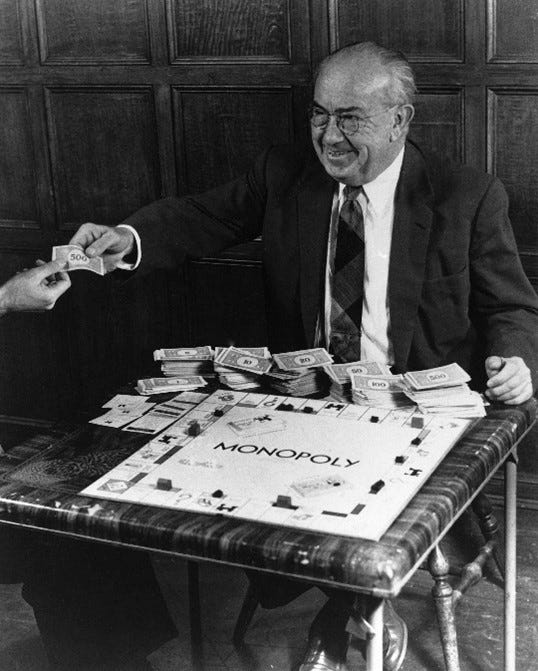

This was during the Great Depression. Charles Darrow was out of work, so he began making custom “Monopoly” game boards at home. He and his family hand-colored the boards and typed the property cards. Darrow made wooden houses and hotels which he painted green and red. Then he packaged the games in inexpensive boxes and sold them in the Wanamaker’s store in Philadelphia. Sales were good; Darrow’s game was very popular.

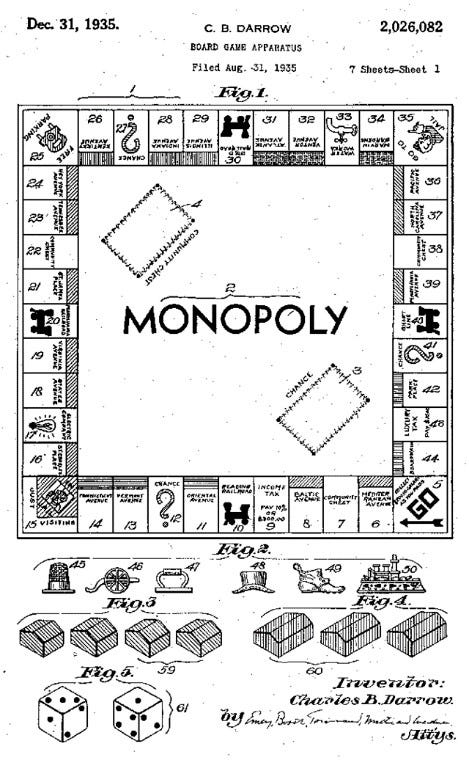

In 1935, Charles Darrow applied for and received a patent. Although Elizabeth Magie had received a patent in 1903 and renewed the patent for the original Landlord’s Game in 1921, the similarity of Darrow’s design to Magie’s game was overlooked.

Parker Brothers Co. became aware of the excitement about the Monopoly game. They purchased the rights from Charles Darrow and began to produce Monopoly. Sales took off and Charles Darrow became a very wealthy man.

To protect the company from infringement and copyright lawsuits, Parker Brothers also bought the rights to other similar games, including The Landlord’s Game. They paid Elizabeth Magie $500 for the purchase of The Landlord’s Game rights and for two of her game ideas. Parker Bros. promised to produce games but stipulated that she would not receive royalties from any future sales. Lizzie was thrilled that her “Landlord’s Game,” a way to teach about economic injustice, would finally reach a wider audience.

That didn’t happen.

Elizabeth Magie Phillips died in 1948. Her obituary gave no indication that she was a board game inventor.

The story doesn’t end there.

It wasn’t until 1973 that Elizabeth Magie Phillips’ role as the creator of the Monopoly game, came to light. Oddly enough her connection to the beginning of Monopoly became known because of a lawsuit filed by Parker Brothers against Ralph Anspach.

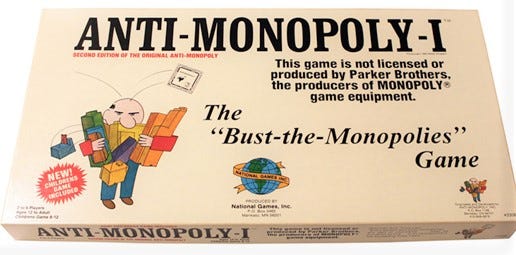

Anspach, an economics professor at San Francisco State University, had designed a new game which he called Anti-Monopoly. The players of the game were cast as lawyers whose job was to break up the wealthy, price-gouging conglomerates through indictments. When the game began to gain too much popularity and sales competed with the Parker Brothers’ Monopoly, Anspach was sued for patent infringement.

In his battles against the intellectual property case, Anspach discovered the Elizabeth Magie Phillips’ patents. Anspach argued that the game’s history showed that Elizabeth Magie Phillips’ original game concept had passed into common use through homemade versions like what Charles Todd had passed along to Charles Darrow and which Charles Darrow had patented and then sold as Monopoly. Anspach won the case on appeals in 1979. It was determined that the trademark Monopoly was generic. However, that decision lasted until 1984. Parker Brothers and Hasbro, the parent company, continue to hold the Monopoly trademarks. However, Anspach reached a settlement and continues to sell his game under a license held by Hasbro.

I guess you could say that Monopoly is still the winner.

Thank you for reading! What’s your favorite board game?

Please share your comments, pictures, or memories. I’d love to hear your stories. You can comment below or email me at mhelmers@andoverhistoryandculture.org

Marilyn

Resources

Library of Congress – Game of Monopoly Patent

a fascinating history! I figured out that monopoly is best when played by more than 2 people. Otherwise, each player owns half the board & the same heap of money changes hands again and again

Marilyn, thanks for another interesting article. I can't wait to play Monopoly again and explain to the other players the history of the game.