The Carter Family and the Perkins School for the Blind

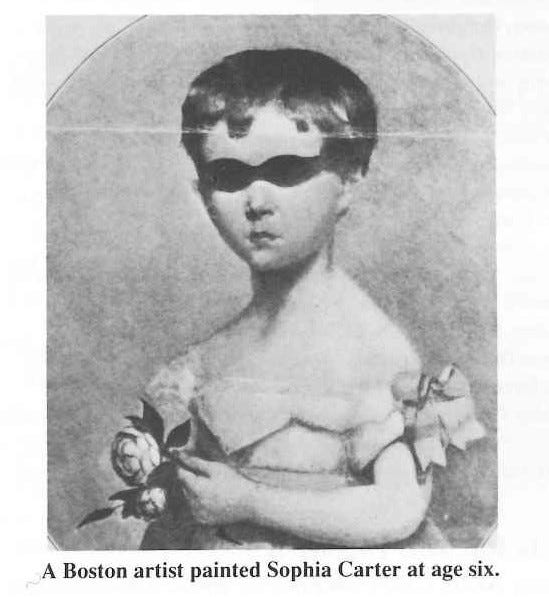

Abby, Albert Alonzo, Edward, Gilbert and Sophia Carter, five siblings out of a brood of 11, were born blind. Their parents, Richard and Abigail, were farmers in Andover.

Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, hit that subscribe button to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

The corner of South Main Street, Rattlesnake Hill Road, and Rocky Hill Road, where Tavern on 28 is now, was once known as Carter’s corner. Several generations of the Carter family owned land in this vicinity. One of their homes, a large green Picturesque Greek Revival, stands at the corner of Rocky Hill Road and South Main.

Abigail (Abby), Albert Alonzo, Edward, Gilbert and Sophia Carter, 5 siblings out of a brood of 11, were born blind. Their parents, Richard and Abigail, were farmers. It’s not hard to imagine that nineteenth century education, medicine, and culture would leave those children behind.

Enter Samuel Gridley Howe, founding director of what would become the Perkins School for the Blind.

Howe learned of Abby and Sophia decided to pay a visit to Andover in 1832. When he reached the toll house, the sisters were visiting with the toll keeper. Writing in 1874, Howe remarked that,

It was a touching and interesting scene—that of two pretty, graceful, attractive little girls, standing hand in hand, and, though evidently blind, with uplifted faces and listening ears, as if brought providentially to meet messengers sent of God, to deliver them out of darkness.

Their mother Abigail was worried about the future of her blind children. She agreed to let Dr. Howe take charge of her daughters’ education. And they received a well-rounded one.

[Sophia’s] education included the common English branches and many of the higher courses of study, vocal and instrumental music, the French and German languages, the household arts and worsted work.

Abby and Sophia were frequent traveling companions of Howe as he campaigned for public education for people who were blind.

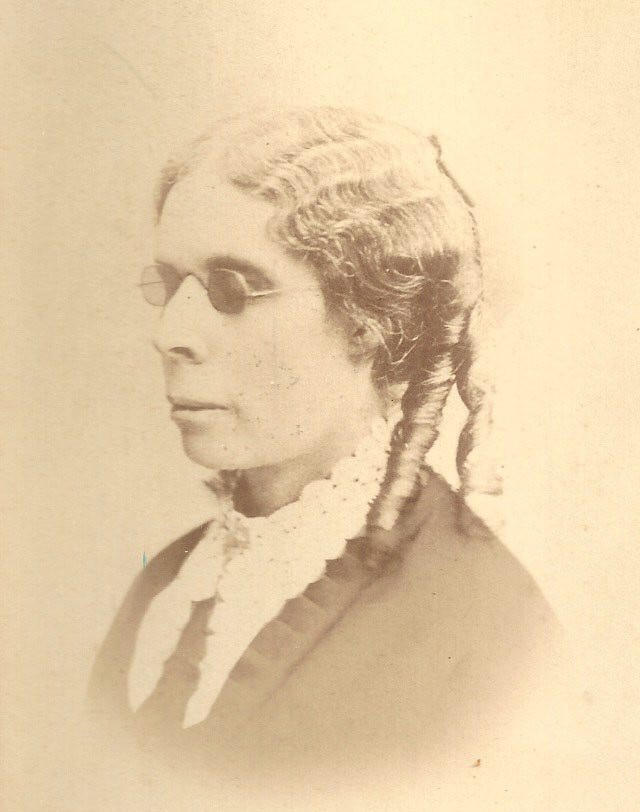

Both sisters went on to become teachers. Abby was a music teacher in town, educating students at Abbot academy and in the public schools. Sophia taught at Perkins for 16 years. A History Center newsletter from 1991 notes that Abby went back to Perkins to teach when Sophia resigned her position. Their musical efforts continued outside the classroom. Abby sang at South Church. Sophia’s vocal talent at the Essex Street church in Boston was widely praised.

Sophia returned to Andover in 1859 and took up the fiber arts. Emily, a sister, relates that “she accomplished a marvelous amount of beautiful work in sewing, knitting, and crocheting.” Sophia’s perseverance was almost “painful to witness.” Her work sold well. She also spent her time helping out with the housework. I wondered why Sophia would leave a position that offered her independence and influence. But her father Richard Carter passed away in 1854, leaving behind many living children.

Emily marveled at Sophia’s “fortitude under affliction” and her “uncomplaining acceptance” of her life’s hardships. I wonder if Sophia was struggling with illnesses, either physiological or psychological. Then again, her obituaries mention that she was generally in good health.

Abby pursued poetry and her work was published in local newspapers. The vertical files at the history center contain a copy of To See Is To Be Happy, written in 1849. Abby wrestles with whether or not she wants the sense of sight. Her belief was that God chose to withhold it from her. And she seemed okay with that. A hand-written memorium to Abby records her thoughts:

I regard my blindness as the greatest blessing of my life for because of it, together with the grace and blessing of God, I have been able to accomplish so much.

Sophia and Abby are the most well-known Carter siblings. I’ve pieced together a few details about the others from Emily’s accounts, newspaper databases, and Perkins itself.

Abby (June 9, 1824 - April 26, 1875)

Sophia (July 12, 1826 - October 11, 1888)

Gilbert (1815 - 1827) died in childhood.

Edward (October 29, 1829 - August 30, 1881) learned how to tune pianos during his course of study at Perkins. He tuned for private individuals and was an employee of Jacob Chickering, the Andover piano manufacturer. Emily tells us that Edward made a decent living selling pianos. I haven’t found his name in a newspaper ad. Yet. At home, he kept dairy cows, caned chairs, and made repairs to the buildings on the family’s property.

Edward contributed to discussions at town meeting and at church. “His voice… always commanded a hearing because of his earnestness of purpose and spirit and clear, sound judgment in all matters of general concern.” He was a member of South Church’s social committee.

Alonzo (October 23, 1840 - August 22, 1866) did not fare well. In addition to his blindness, he lost hearing in one of his ears. His first enrollment at Perkins wasn’t a happy one. Afterward, Alonzo got a job in the classics department at Phillips Academy. He used specialized boards that he prepared in advance to do Greek and Latin translations in class. Alonzo’s dreams of further education were thwarted.

He returned to Perkins in 1860 to train as a music teacher and traveled alone around the Boston area. Alonzo’s compromised hearing robbed him of the ability to know where sounds came from. Emily “regarded the years in which he taught music and went about alone in the city of Boston as a living tragedy. It was more than he could bear.” Nothing pained Alonzo more than having to sit by while his country went to war.

Despite what happened to him, Alonzo saw the “humorous side of every thing” [sic], even his own difficulties. Emily tells her readers that “his merriment was contagious.” Alonzo perished due to a fever. I wonder if Emily felt particularly protective toward Alonzo. She saw his difficulties in a world that was ill suited a person living with vision loss, let alone both vision loss and hearing loss.

A letter that Alonzo wrote to his alma mater, then called the Massachusetts Asylum for the Blind, was published in an 1864 report.

It is now two years since I left the institution, and I am happy to say that during that time I have been able to support myself almost wholly by my own exertions ... I have tuned the pianos of all my pupils and as many more as I could find.

He put a much more positive spin on his situation than his worried sister would.

This History Buzz story is close to home for me. I heard mention of the Carter siblings once or twice during childhood and the cobwebs got dusted off when I read a suggestion in another History Buzz post. I feel there is more to learn about the siblings. And I hope to add to their story soon.

Thanks for reading!

Doug

Please leave us a comment. We love to hear from History Buzz readers!

Further Reading:

Andover Center for History and Culture’s vertical files on the Carter family.

Andover Historic Preservation entry about 4 Rocky Hill Road

https://preservation.mhl.org/4-rocky-hill-rd (last accessed February 11, 2025)

Edward Carter. Obituary. Lawrence American and Andover Advertiser. September 2, 1881

https://mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/LAM-1881-09.pdf (last accessed March 1, 2025)

Massachusetts School for the Blind. The Congregationalist. July 9 1873.

Miss Sophia B. Carter (obituary). Andover Townsman. October 12, 1888

mhl.org/sites/default/files/newspapers/ATM-1888-10.pdf (last accessed February 11, 2025)

Sophia B. Carter (obituary). The Congregationalist. October 18, 1888.

In addition to an archives page on its own website, the Perkins School maintains a presence on both Internet Archive and Flickr. Note that the tendency to get sidetracked is very strong.

This article added a great deal to my knowledge of services available for peoples with disabilities in the 1800s. I am so impressed with the resilience and perseverance of the Carter siblings. Thank you.

Doug, what a fascinating article! The Carter siblings were certainly determined to thrive despite their disability. Thank you for sharing !!