Welcome or welcome back to History Buzz! If you’re a subscriber to the Buzz, thank you! If you’re new here, or you haven’t become a subscriber yet, hit that subscribe button to have History Buzz delivered directly to your inbox. If you can, please consider a paid subscription to support the research and writing that make History Buzz possible.

The Supermarine Spitfire, an icon of the air battles of World War II, was first delivered to the Royal Air Force in 1938, barely a year before Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland. The “Spit’s” elliptical wings reduced drag and increased speed, giving the plane handling capabilities that were astounding for the time. Power came from a single, 12-cylinder Rolls-Royce engine known as the Merlin.

During the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940, Royal Air Force pilot David Standford Tuck was chasing a German aircraft that went into a steep dive and leveled off at the treetops. As he got the fleeing plane in his sights, something didn’t “feel” right. The problem: Tuck was headed straight for power lines! He pulled up on his controls and the nimble spitfire responded instantly. Regaining his composure, Tuck throttled up the Merlin engine and caught up to the Messerschmitt. “He pulled the trigger and sent a short burst from his eight .303 Browning Mk II machineguns into the German fighter, causing it to crash.”

The Spitfire saw action in the UK, Europe, and the Pacific. And I could write about all of it. But not in this edition of History Buzz.

Spitfires paid for with fundraisers were called presentation spitfires or subscription spitfires. The idea originated with Lord Beaverbrook, Britain’s minister of wartime production. If an individual or a group could raise 5,000 pounds, an aircraft could be inscribed with a name of their choice.

While President Roosevelt and many Americans were sympathetic to Great Britain as it faced an invasion by Nazi Germany, the United States government was neutral and would stay that way until November, 1941.

The selectmen of Andover, Massachusetts had been in-touch with “Old England” Andover about ways in which we could be helpful as early as 1940. S.R. Bell, the mayor of Andover, England replied that spitfires were sorely needed and asked that residents of Andover, Mass be made aware of his town’s spitfire fund.

Our branch of the spitfire campaign kicked off at the very end of January 1941. And it was serious. The town’s population was far less back then, but a door-to-door campaign was envisioned. Cornelius Wood wrote a witty, motivational letter to the editor. Calling the reader’s attention to a $6,500 goal (including North Andover), Mr. Wood declared that the 500 bucks an “eyesore” that he would remove with a check to the spitfire fund. What a way to stir the towns into action!

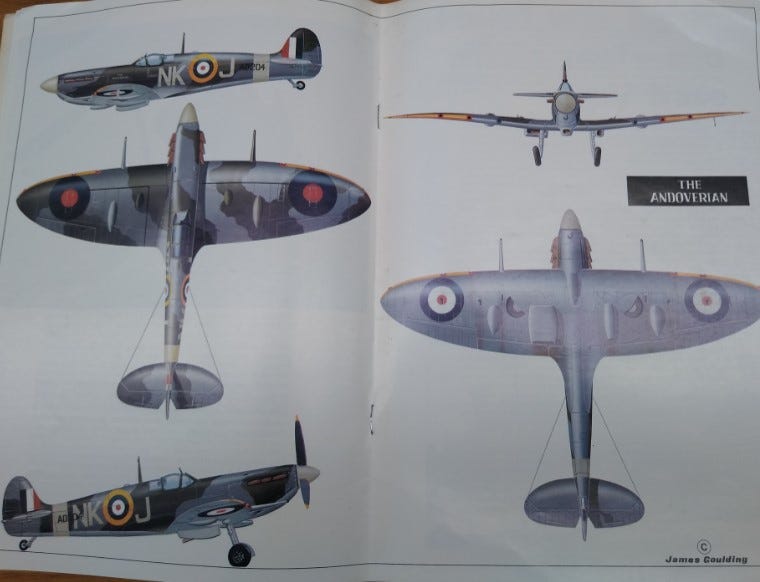

The spitfire campaign in Massachusetts closed on May 9, 1941. The check needed to arrive in “Old England” before their campaign closed. Andover and North Andover, Mass sent along $4,214.50 Sufficient funds were raised to purchase a spitfire. “Our” spitfire, a mark Vb was dubbed The Andoverian. She was built and on the tarmac in the summer of 1941.

The History Center owns a copy of Johnnie Spitfire, a book detailing the Andoverian’s career. It is a short, yet interesting read. The reader needs a grasp of Royal Air Force parlance, and a map. Access to an internet search engine and an interest in World War 2 helps as well.

During the ill-fated Operation Fuller in 1942, Flight Sergeant Thomas was piloting Andoverian. He was engaging with German fighter planes (BF109s), and heard two ominous bangs. His starboard wing suffered damage along with his inboard machine gun. Thomas had to “make for England and went down within feet of the wave tops.” Luckily, he did not crash and made it home… almost. Although the Andoverian was based in Ibsley, Thomas landed in Manston. Looking back, the Flight Sergeant considered that his flight back to base was “as hairy a do as flight earlier from the attentions of the BF109E’s.”

In May, 1944, the Andoverian was assigned to number 303 Squadron, composed almost entirely of Polish pilots who went into exile when their homeland fell in 1939. Piloted by Flight Officer Zdanowski, Andoverian flew three sorties on D-Day. The last sortie was especially grueling. “Our” spitfire gave close escort to Royal Air Force planes tugging gliders laden with troops and supplies. No harm came to the gliders from enemy fighters. Glider borne troops faced many hazards before they even engaged with the enemy.

Andoverian left the 303 squadron when its spitfire fleet was updated in the summer of 1944. She did not fare well in her next posting with 120 squadron. Her undercarriage collapsed at the end of a landing run and the pilot, Flight Sergeant Pollock, vacated the cockpit too hastily. Somebody tried to blame Pollock for damaging the plane in a particularly heavy landing. The official finding was that the uncommonly rough air strip at Merston caused the accident.

The end of Andoverian’s “operational” career was spent as a spotter aircraft. During a four-day stretch in November 1944, Andoverian monitored shell bursts from the guns of HMS Erebus as the ship fired upon German gun batteries on Walcheren in the Netherlands. From January 1945 on, Andoverian served as a training aircraft with two separate operational training units. She stayed with number 58 O.T.U. until August of 1945.

A significant chunk of the Andoverian’s career consisted of scrambling to intercept the “occasional plot”, providing escort duty for home-bound Coastal Command aircraft looking for U-boats, or protecting shipping convoys in the English Channel. Her service was necessary and important. Johnnie Spitfire notes that “although no enemy aircraft fell to the cannons and machine guns of “The Andoverian”, the spitfire had more than played its in supporting the team that went towards defeating the Forces of Festung Europa”.

Andoverian was recycled. Sometime between August of 1945 and June 21, 1947, she fell to an acetylene torch… and not the Luftwaffe. Johnnie Spitfire notes that her remains probably went into making pots and pans for Britain’s kitchen and “the new generation of peace-time families”.

Upon his retirement in 1943, Mayor Bell sent a photo of the Andoverian along with a letter,

“I feel that I cannot allow the occasion to pass without conveying through you to the people of Andover, Massachusetts, a message of greeting from the people of Andover, England, and a renewed expression of our thanks for your generous gestures of friendship and sympathy at that period in the war, when, although are spirits were undaunted, we were alone in our struggle against Hitler and the Nazis and all the evil things which those words imply."

And that is how Andoverian should be remembered.

Thanks for reading! Leave a comment and let me know. We love to hear from History Buzz readers! If you enjoyed this story please consider becoming a subscriber to the Buzz. Your subscription - free or paid - helps share History Buzz with even more history lovers!

~Doug

Further Reading

Andover Townsman. Available online via Memorial Hall Library.

January 2, 1941 January 30, 1941 February 13, 1941 February 20, 1941 May 8, 1941 December 16, 1943.

Aviation Trails. Operation “Fuller” - The Channel Dash. Last Accessed June 30, 2024

Rotary International of Great Britain and Ireland. Map of WW2 operational airfields in the UK. Last Accessed June 14, 2024.

David Kindy. Remembering the Spitfire. Smithsonian Magazine June 4, 2021. Last Accessed June 16, 2024

Molva. Johnnie Spitfire : being an account of the history of the Presentation Spitfire "The Andoverian”

Office of the Historian (U.S. Department of State) The Neutrality Acts, 1930s. Last Accessed June 23, 2024

Doug, another fascinating story!! I learned a great deal from your research.

Well done!!!

What an engaging wartime history of an airplane and its sponsors on both sides of the Atlantic! Woderfully detailed.