Long Memories, a history of Andover in ten (or so) trees: Samson's Hockey

The story of a beloved landmark sheds light on the region's indigenous people, the early days of AVIS, and the family of Sid White, Andover's best remembered dairyman.

Did you know that the first conservation acquisition by AVIS, Andover’s 128-year-old land trust, was not a tract of open space but a tree?

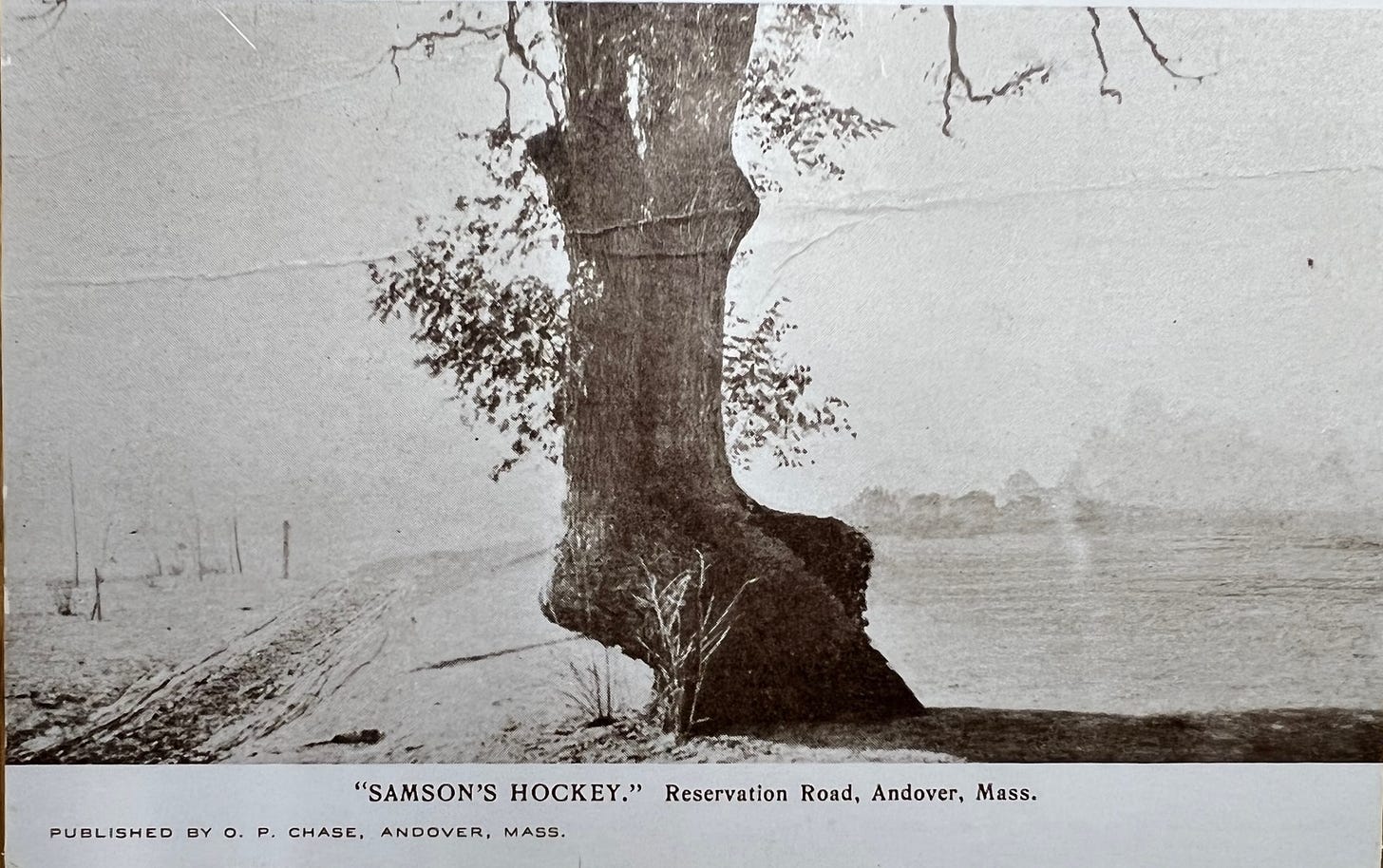

The picturesquely contorted oak known as “Samson’s Hockey” was a beloved landmark in the West Parish neighborhood known in the 19th and early 20th centuries as “Happy Hollow.” Old deeds along what is now Reservation Road measured distances from “the crooked tree,” and in 1826 when the West Parish church district was established, the tree was one of the boundary points between the South and West Parishes.

This natural curiosity was named, according to a letter printed in the Andover Townsman in 18971, by a group of boys in the late 1840s. “Hockey was a great game when we were boys,” reminisced Dr. John G. Johnson of Brooklyn, New York, who was born in 1833 and grew up at 25 Central Street, now Christ Church’s Glebe House. The boys were cutting through the woods one day, perhaps on their way or returning from some frozen pond nearby, when Johnson’s older brother Samuel called their attention to the tree’s odd shape.

George Baker, on whose family farm acreage (now 5 Argilla Road) the tree was located, said, “What a magnificent hockey it would make.” He was using the word ‘hockey’, as was common then, to reference the hooked wooden stick and not the game itself. The boys likely played a version of “shinny” or “keep-away” brought to New England by French-Canadian immigrants, as the rules of the modern game were not organized (on either outdoor or indoor rinks) until much later in the century.

“Yes,” replied Samuel Johnson that long-ago day. “But it would take Samson to use it.” The boys, along with most Andover residents of the 19th century, were well versed in the Bible and familiar with the story of the legendary Israelite strong man.

The name stuck.

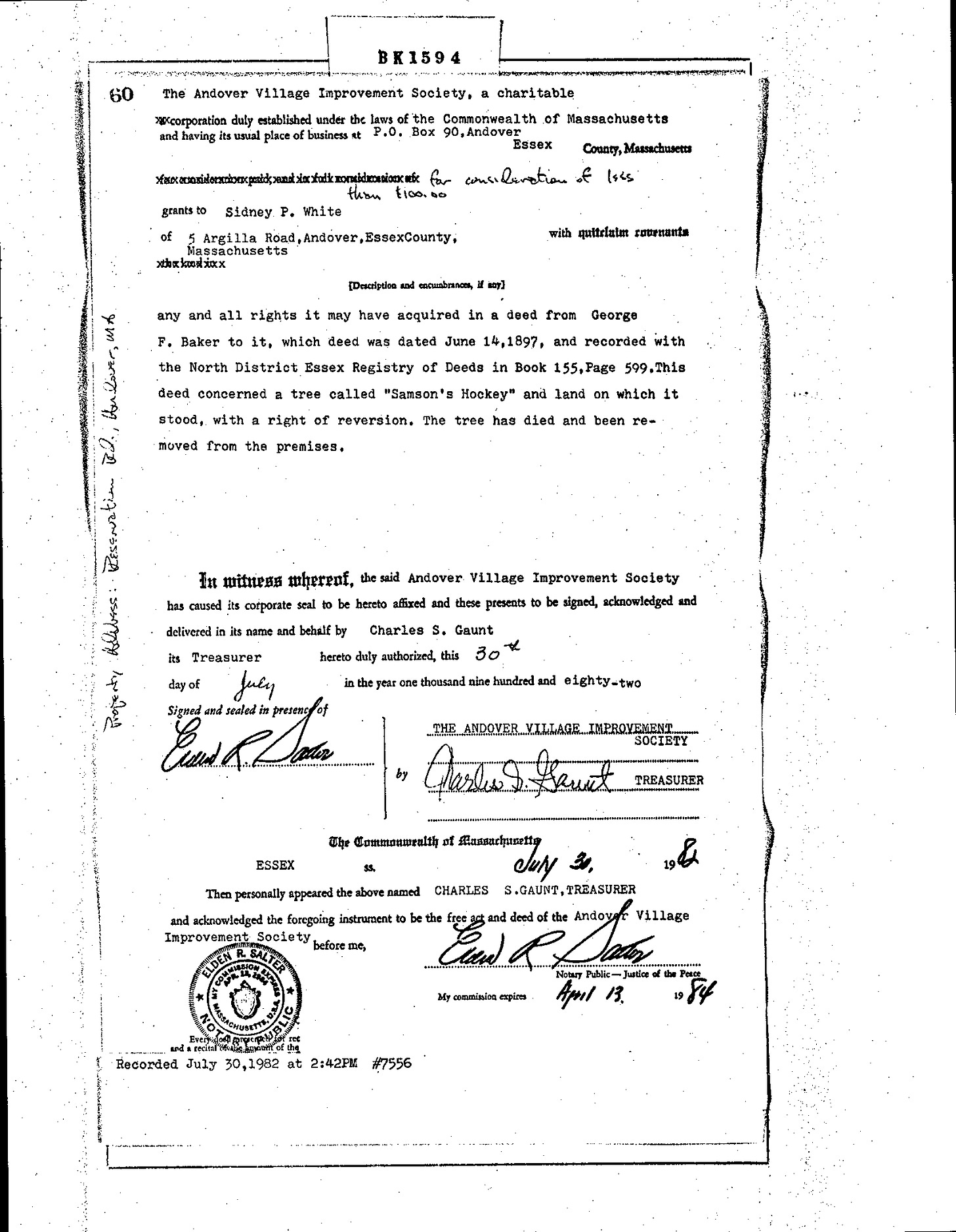

George Baker grew up to inherit the Argilla Road farm. He married Charlotte (Blanchard) in 1860 and had three children. After his eldest daughter Ina was married in 1896 to Herbert Lincoln White, he deeded her two acres along the now-Reservation Road for a house lot. Desiring at the same time to preserve Samson’s Hockey, he deeded the tree to the three-year-old Andover Village Improvement Society together with its surrounding ten-by-ten-foot square of land.2

The glacial esker Indian Ridge across the road and its surrounding woodland were acquired for the town six months later and placed under the guardianship of the newly formed Indian Ridge Association. Samson’s Hockey then became the prominent marker of the western entrance to the new Reservation’s scenic carriage road.

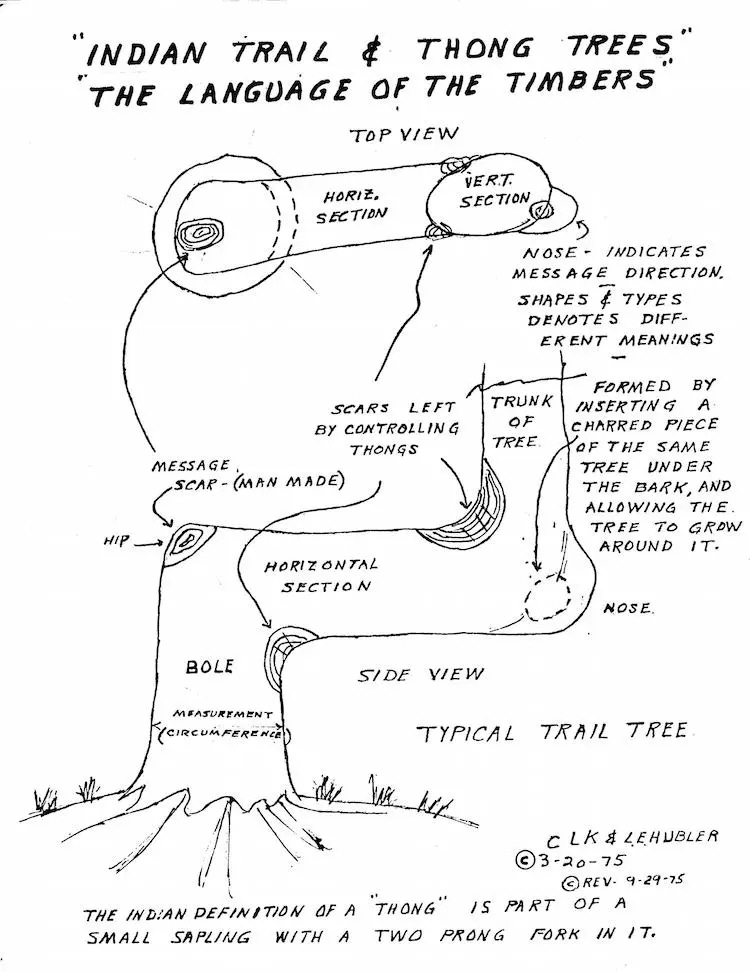

Members of AVIS’s Committee on Preservation of Natural Beauties were intrigued not only by the tree’s unusual appearance but by speculations on how it had come to be formed. “Indians were known to have bent tender branches of young saplings so they might be distinguished as landmarks,” wrote AVIS founder and Secretary Emma Lincoln in the organization’s 1898 report. 3 “Our tree may have received its first twist from just such hands and for a similar purpose.”

Was this theory, as many people have thought over the years, an example of Emma Lincoln’s well-known fondness for romantic ideas about the natural landscape? Or could the idea of trees intentionally modified by Native Americans trees have a basis in fact? The question has been widely debated in the years since. Several organizations in the Southern and Midwestern United States, including indigenous and tribal groups, continue to catalog, assess and work to preserve these so-called trail trees, also known as prayer trees or thong trees. 4

The first known research on marker trees was carried out in the 1930s and 40s by geologist Dr. Raymond E. Janssen. As Janssen noted in 1941,

Among the many crooked trees encountered, only a few are Indian trail markers. The casual observer often experiences difficulty in distinguishing between accidentally deformed trees and those ... purposely bent by the Indians. Deformities may occur in many ways. A large tree may fall upon a sapling, pinning it down for a sufficient length of time to establish a permanent bend. Lightning may split a trunk, causing a portion to fall or lean in such a way as to resemble an Indian marker. Wind, sleet snow or depredations by animals may cause accidental deformities in trees. However, such injuries leave scars which are apparent to the careful observer, and these may serve in distinguishing such trees from Indian trail markers.5

As a product of his research and consultations with a number of tribal elders, Janssen proposed the criteria used to this day to help distinguish a purposely deformed tree from a natural phenomenon. First, the tree must be old enough to have been a sapling during years when Native peoples were known to have lived in the area. Second, the horizontal bend should be neither too low nor too high: ideally between 4 and 5 feet from the ground. And third, the tree should be pointing toward something significant in the natural landscape. Photographs indicate that Samson’s Hockey fits the first two of these criteria and, with its proximity to the Shawsheen River, the raised hunting vantage of Indian Ridge, and the iron-rich (or “red”) mineral spring (located near what is now 64 Red Spring Road), it appears to satisfy the third.

We can’t ever be sure, but it’s possible that Emma Lincoln was right: Samson’s Hockey may well have been deliberate human creation and not a freak of nature.

As the town of Andover grew and changed around it, Samson’s Hockey survived fires, moth infestation, and the hurricane of 1938 before succumbing to rot sometime around 1980. The Argilla Road farm and White family house (now 10 Reservation Road) had passed meanwhile to George Baker’s grandson, Sidney Pratt White (1899-1983). A gentleman dairy farmer and town Selectman, local legend “Sid” White was the owner of the Rose Glen Dairy Bar where generations of Andover residents bought ice cream cones and fed ducks on summer evenings. In July 1982 as the aged Sid White was putting his affairs in order and preparing to sell his property, AVIS cut the dead tree down and, per George Baker’s original deed, conveyed the title to the one-hundred-square-foot plot back to his heir.

More to come . . .

In the next entry of “Long Memories” I’ll share another story of a historic town tree. I love questions and comments. Click here to open a free Substack account, so you can like, share, and comment.

Thanks, as always, for reading!

Jane

History Buzz is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Andover Townsman, October 13, 1897

Essex County Registry of Deeds

Annual Report of AVIS, 1898, Andover Center for History and Culture Collection.

see, for example, http://www.greatlakestrailtreesociety.org/trail_tree_about.html

“Trails Signs of the Indians,” by Raymond E. Janssen, Natural History Magazine, February 1940. https://archive.org/details/naturalhistory45newy/page/116/mode/2up?q=Janssen&view=theaterDr.

Fun article, Jane! Nice history on how hockey came to New England. And I never knew about Native American trail trees. Nice “how to” diagram, too!

My first thought on seeing the 1906 post card was of a giant horse's fetlock!