ACHC #1911.022.8

Antimacassars or “tidies” aren’t seen much anymore. But during the 1800s, they were a necessity in every parlor. Made of lace, crochet or plain fabric, these washable cloths protected the upholstery of couches and armchairs.

What prompted their importance? Blame it on a London barber.

About 1783, Alexander Rowland (1747-1823) invented his “unguent for the hair.” It was common for barbers to make their own oils and elixirs for their customers. The slicked down hairstyles that were popular for men in the Victorian era required the use of a hair oil. Rowland’s Macassar Oil made hair shiny and sleek.

Rowland launched an aggressive advertising campaign praising the effectiveness of his oil. He maintained that his oil was made from a combination of oils including that of the macassar tree of Indonesia.

"The Proprietors of the Macassar Oil can proudly appeal to an enlightened and judicious Public for the unrivalled efficacy of this Oil. They wish not to deceive or delude by rhetorical declamations or bombast language — they solicit only the test of experience, and with confidence they can affirm, that the more it is known in a higher degree of estimation will it be held. The utility is evinced by preserving the hair from falling off or changing colour, and its elegance by producing the most smooth and beautiful gloss ever known."

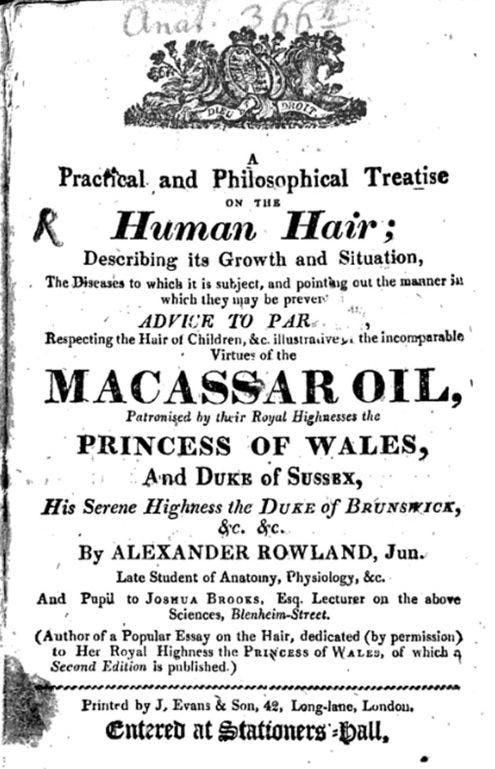

In 1814, Alexander Rowland’s Practical and Philosophical Treatise on the Human Hair Describing its Growth and Situation was printed. It explained the “incomparable Virtues of the Macassar Oil” for both men and women.

Public Domain

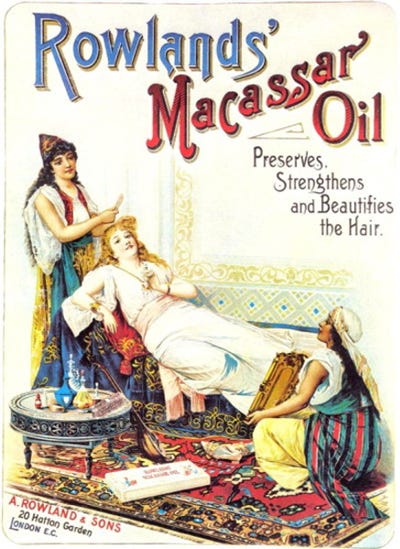

Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

The fashion for oiled hair was widespread. What was a lady to do to keep her parlor furniture unspoiled from oily heads?

Women began to put fabric pieces on the backs of couches and chairs to protect the upholstery. Often matching covers were placed on the furniture arms too. By the 1830s, the cloths were referred to as antimacassars. The need for upholstery protectors wasn’t limited to parlors. In the 1860s, theaters began using antimacassars too.

ACHC #2013.054.8ab

By the late 1880s, recipes for making hair oil abounded. Even The 1887 White House Cookbook included instructions for making “Macassar for the Hair.”

“Renowned for the past fifty years, is as follows: Take a quarter of an ounce of the chippings of alkanet root, tie this in a bit of coarse muslin and put it in a bottle containing eight ounces of sweet oil; cover it to keep out the dust; let it stand several days; add to this sixty drops of tincture of cantharides, ten drops of oil of rose, neroli and lemon each sixty drops; let it stand one week and you will have one of the most powerful stimulants for the growth of the hair ever known.

Another:—To a pint of strong sage tea, a pint of bay rum and a quarter of an ounce of the tincture of cantharides, add an ounce of castor oil and a teaspoonful of rose, or other perfume. Shake well before applying to the hair, as the oil will not mix.”

It wasn’t until 1888 that A. Rowland & Sons of London received the trademark for “Macassar Oil.” Sixty-five years after the death of its inventor, Alexander Rowland.

Antimacassars didn't died out with the Victorian era. Even today some train and airplane seat backs sport cloth disposable or removable, washable coverings. Those too are there to protect the upholstery from oily heads.

Do you remember antimacassars?