Frye Village Stories: Oh, the things I've learned about sheep and degreasing! (pt2)

A Shawsheen Village 100 Story

Before Shawsheen Village Frye Village Stories

Oh, the things I’ve learned about sheep and wool!

Because there are so very many steps in fleece and wool production, I’m going to focus on wool “scouring” and “degreasing”….. because, as it turns out, there is a difference that is at the heart of the story.

A raw sheep fleece can be up to 85% material other than wool fiber, depending on the breed of sheep and where and how the sheep lives.

The "vegetable matter" that accumulates in the fleece can be removed by mechanical means, either hand-picking or mechanical.

Aside from the vegetable matter, dirt, dung, dust, and other things that find their way into a sheep’s fleece, there are two key products that occur naturally on a sheep: grease (also called wax) and sweat salts (suint). Grease is produced from the sebaceous glands in the skin. Suint is mainly salts left behind from the sheep’s sweat.

Wool scouring

Grease and suint, however, can’t be removed mechanically, and two different techniques are needed to address each.

Each product has different solubility. Because suint is a salt, water can be used to remove it. Grease, however, needs a solvent of some kind. Soap and “lees” (stale urine) are two traditional solvents. The alkalinity of the soap used needs to be factored in as well. Too much in either direction and the quality of the wool is impacted. Olive oil based potash soap was one preferred method.

Wool scouring waste water and contaminants could be converted into other profitable materials from fertilizer to lanolin. But it wasn’t always done due to the greasiness of the breed of sheep, labor, time, and profitability.

Either way, water downstream from wool washing was often contaminated. Lawsuits between businesses needing clean water appear frequently in newspapers. According to one Australian account, “The organic effluent load from a typical wool scour is similar to that of the sewerage from a town of 30,000 people.” That’s a lot of waste.

In the Merrimack Valley, E. Frank Lewis Co. and the American Lanolin Co. were of the largest wool scouring plants in the Lawrence mills, and at other mill locations. The city is mentioned frequently in the journal of the American Wool and Cotton Reporter.

As production increased throughout the Industrial Revolution, manufacturers sought new ways to scour raw wool.

The U.S. Patent office lists hundreds of wool processing inventions: wool pickers, washing machines, scourers, carbonizers (for turning vegetable matter into carbon), and driers, along with methods to recover the grease and oil for other uses.

Wool degreasing: A potentially explosive business

A major innovation at the turn of the last century was the introduction of powerful chemical solvents to “degrease” the wool. One of the most common was naptha petroleum, a highly flammable material. A major argument for using chemical solvents was the increased ability to extract clean, usable grease.

Although many safety features were invented and patented, explosions in wool degreasing plants were not uncommon. Explosions in degreasing plants in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, and Norton, Massachusetts caused hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage. Fortunately, the Norton explosion occurred after business hours so no lives were lost. (The Norton fire plays a role in the story going forward.)

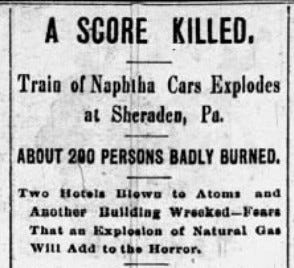

Fall River Daily Evening News, May 13, 1902

In May 1902, a train of cars carrying naptha petroleum exploded in Sheraden, Pennsylvania, leaving 200 people badly burned. At the time, it was estimated that as many as 75% of the victims would die of their burns.

A switch light on the train line ignited leaking naptha, causing an explosion that shot flames 50’ into the air.

Escaping naptha traveled a mile and a half wreaking havoc as it traveled. The Seymour and Sheraden Hotels blew up, along with other buildings. The first car exploded at 4:40 in the afternoon, attracting a crowd of onlookers. The second car exploded at 5:00, and the last three at 6:15. Many in the crowd were rendered unconscious by the explosions and gas fumes.

Back in Frye Village

In May 1902, the same month as the Sheraden, PA, fire, the Smith & Dove mill in Frye Village was sold to the American DeGreasing company, headquartered in New York City. Robert Brailsford represented the company in the sale.

As hinted at in last week’s story, the history of the wool degreasing plant in Frye Village was a short-lived venture. The Frye Village degreasing plant was out of business in six short years, closing in 1908.

Fortunately for residents of Frye Village, the failure of the plant was not due to the explosive nature of the chemicals used. Management of the business was a major contributor. While the ownership of the property didn’t change, the managers of the project changed a number of times and plant managers came and went. Eventually leading to bankruptcy for the business and the local plant manager, whose Andover home was sold at auction shortly after the plant closed.

The how-to of history

The challenge in uncovering the story was that none of the first reports I found included the names of the people involved. There were plenty of veiled references, innuendo, and anonymous comments, but no names.

I followed the story from the Andover Townsman to the Wool and Cotton Reporter, Boston Globe, Fall River Evening News, New-York Tribune, Brooklyn Times Union, Camden NJ Morning Post, the U.S. Patent office, census records, and street directories, before finding what I was seeking in an Australian treatise on wool production.

My journey led to a story that included failed businesses, bankruptcy, lawsuits, and arrests. The story is, as one reader put it last week, a true “soap opera” that I’m looking forward to sharing with you next week.