Frye Village Stories: the Smiths & Doves, Anti-slavery, abolition, and the Underground Railroad (part 6)

A Shawsheen Village 100 Story

Before Shawsheen Village Frye Village Stories: the anti-slavery and abolitionist activities of the Smith and Dove families

Researching Anti-Slavery, Abolitionism, and the Underground Railroad

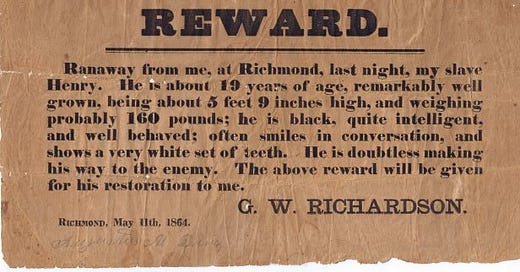

Although slavery was abolished in Massachusetts in 1789, it was still legal in many other states until the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Fugitive Slave laws of 1793 and 1850 made capturing and returning enslaved people a lucrative business.

Those who made it to free states like Massachusetts lived under the shadow of national laws that favored those who had enslaved them. Free Blacks had worked since the 1700s to end slavery. Free Blacks provided aid and protection to fugitives. Their work was the foundation and heart of what we know of as the Underground Railroad.

It’s important to remember that the Underground Railroad was an illegal activity that carried the risk of heavy fines and imprisonment for those who were actively transporting and protecting fugitives.

Because of this, evidence of stops along the Underground Railroad and of those who helped people to freedom most often comes from oral histories, letters, and narratives of formerly enslaved people and Abolitionists.

ACHC #1970.046.1

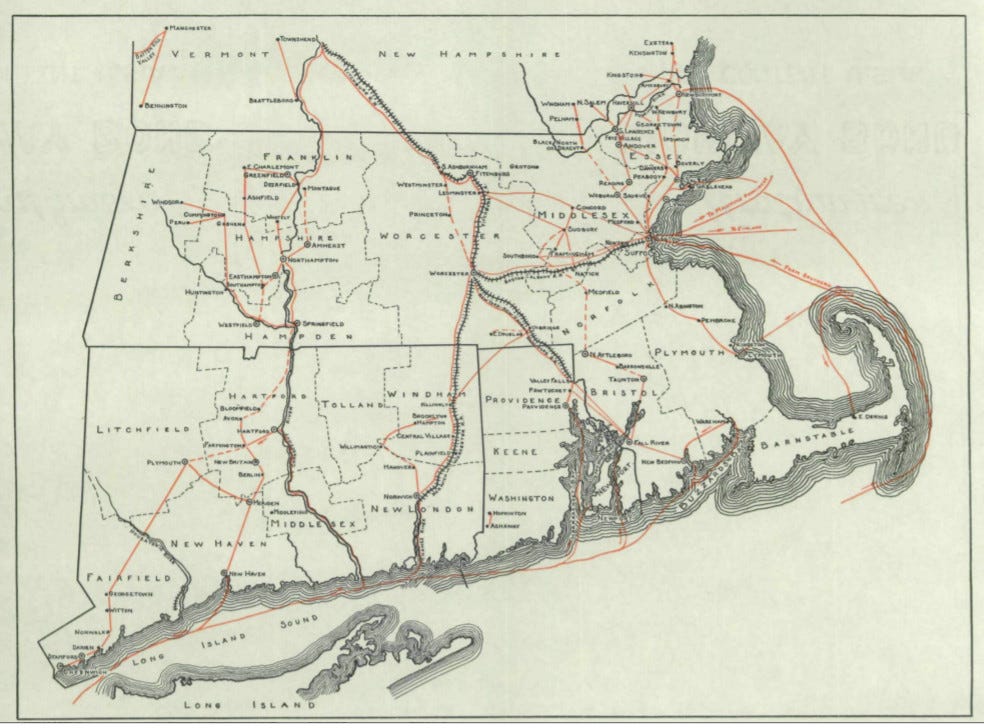

A frequently quoted source is a History of the Underground Railroad in Massachusetts written by Professor Wilbur H. Siebert, and published in 1936 in the Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society.

Professor Siebert’s sources were letters from former Abolitionists, memoirs of formerly enslaved people, reports by Anti-Slavery Societies, as well as the Treasurers Accounts of the Boston Vigilance Committee to Assist Fugitive Slaves.

The article also includes a map of Underground Railroad routes through Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. Frye Village and Andover are noted as stops.

One of Professor Siebert's publications

Professor Siebert's map

You can read more about Professor Siebert and his work to document the Underground Railroad on the History Center’s website.

Andover & Anti-slavery

The anti-slavery and abolition activities of Andover and Frye Village residents are well documented in church records, newspapers, personal papers, and organizational records. Many of the Underground Railroad stories for Frye Village (and many other Massachusetts towns and villages) come from Professor Siebert’s article.

According to Siebert, fugitives traveled along the Boston-Haverhill turnpike, and crossed into Andover at the home of William Jenkins, now 20 Douglass Lane. It was said that Jenkins’ home was an active stop from the 1830s until the 1860s. Jenkins hosted anti-slavery speakers in his home, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, and William Lloyd Garrison.

Professor Siebert also reported that fugitives could also find safety at the Cogswell House, and at the home of Rev. Ralph Emerson. He also quoted this small article from the July 7, 1860 Andover Advertiser.

Frye Village Underground Railroad oral histories

Continuing his description of a fugitive’s path through Andover, Professor Siebert wrote,

“Straight up the “pike” two miles north of Andover Hill was the thriving manufacturing center of Frye Village...There William Poor and his sons had a flourishing wagon factory, Elijah Hussey, a sawmill, and William C. Donald, an ink factory.”

Siebert reported that William Donald, Elijah Hussey, Joseph Poor, and “perhaps others” conducted fugitives out of Andover to their next stops in New Hampshire. This is where we read this story:

“When Mr. Poor heard a gentle rap on his door or other subdued sound in the night, he dressed quickly, went out, harnessed his mare Nellie into (sic) a covered wagon and started...for North Salem, New Hampshire...Mr. Poor was always back in time for breakfast.”

Another reminiscence, reported in the Andover Townsman December 12, 1932, suggests that Elijah Hussey “would have said something about (it); only he didn’t talk about it. The second station was near the (William C. Donald) ink-shop.”

What about the often-told story about Mr. Poor hiding fugitives in a false-bottomed wagon?

What’s interesting is that in Professor Siebert’s article, that story was told about Mr. Israel How Brown, of South Sudbury, Massachusetts, who after hiding his passengers under the false bottom, filled the wagon with produce for the Fitchburg Market.

“He started on his trip of 23 miles at 3:00am, and was only once delayed by officers of the law. They discovered nothing…”

So while there are many things that we do know about John Dove, and John and Peter Smith, their role and the roles their neighbors might have played, in the Underground Railroad can’t be fully documented.

What do we know?

We know that John Dove and John and Peter Smith were abolitionists. In 1866, at the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his landing in the United States John Smith wrote:

“...we arrived in Charleston safely, and I went ashore. I saw a crowd of people collected in a vacant lot. I always went where there was a crowd, and what think you I saw there? It went to my heart like a shock. It was a sale of slaves. I remained and saw them bid off...a woman was put up with a child on each side of her, and a babe in her bosom, and her character was told to the crowd. She wept bitter tears, and it made me weep to see her. She was bid off and my heart recoiled at the sight. If there is anything wicked, it is for one man to take another to make him his beast, to beat him and get all the work out of him possible, and allow him to go blindly down into eternity without knowledge of God.”

Free Christian Church

John Dove and John Smith were also among the founders of the Free Christian Church, along with their neighbors William Poor, Elijah Hussey, and William Donald.

In 1846, forty-four residents left South Church, West Parish Church, the Baptist Church, and the Methodist Society, because the churches would not take a strong stand on the issue of slavery.

ACHC #1964.685, Free Christian Church in its original location on Railroad Street. You can see the stables for horses in the back of the property.

In 1849, John Smith purchased the Methodist Church on Main Street and moved it to Railroad Street. The Free Christian Church was in that location until 1907 when the church on Elm Street was built.

Mrs. Smith was active in the Ladies Benevolent Society of the Free Christian Church. In the 1850s, the Society made, collected, and shipped clothing to Canada for fugitives who made it across the boarder.

ACHC #1998.023.1, John Smith’s name appears on the fly leaf of a copy of Narrative of Sojourner Truth A Northern Slave, indicating that this was his personal copy of her book.

Sojourner Truth sold copies of her narrative at her speaking engagements.

It was reported in The Liberator newspaper that John Dove and John and Peter Smith were supporters of the Andover, the Massachusetts, and the American Anti-Slavery Societies.

In 1836, The Liberator listed John Smith as President and Peter Smith at 1st Vice President of the Andover Anti-Slavery Society, which boasted 400 members.

Because societies of mixed company were frowned upon, Smith reported that 200 of those members “will soon appear in the shape of the 'Andover Female Anti-Slavery Society.’”

In April 18, 1861, John Dove, Joseph Poor, Peter Smith, John Smith, I.M. Hardy, and William Poor led a large meeting, “Frye Village, Wide Awake!” The meeting was called days after the start of the Civil War was declared on April 12, 1861, to determine what could be done to organize a company in case the country should call for service.

The meeting came together with just 7 hours notice, with John Dove as the chair. Thirty-eight men stood up as willing to serve. Before adjourning, the meeting appointed Peter Smith, William and Joseph Poor, and George W.W. Dove to represent the village at the upcoming Town Meeting. Abbott Village and Marland Village also had large delegations.

So there is a lot we do know about the Smiths, Doves, Husseys, and Donalds, and their actions to end slavery in the United States. And some, or even all, of the legends of the roles in the Underground Railroad could be true. Yet we can keep in mind that in both his 1898 and 1936 articles, Professor Siebert recognized both the value of oral histories and first-hand accounts, and the temptation to label them as documentable fact.

The Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage reminds us that oral histories, reminiscences, memories, and stories:

“are valuable not necessarily because they represent historical facts, but because they embody human truths — a particular way of looking at the world.”

And participation in the Underground Railroad, and the drive to help those in need, certainly embody a valued human truth and way of looking at the world.

You can read more about researching Andover and the Underground Railroad on the Research Highlights page of our website.

Coming up, a look at the last generation of Smith & Dove Manufacturing. Before Shawsheen Village: There's more to come!